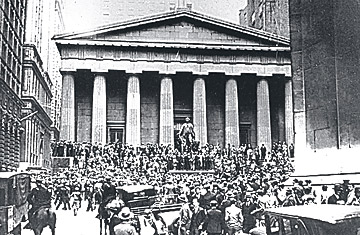

Stocks fell off what Irving Fisher had called a "permanently high plateau" in October 1929 and didn't return until that level until 1954.

Irving Fisher lives on in American economic history mainly as a laughingstock. He was, after all, the ninny who declared on Oct. 15, 1929, that stock prices had reached "what looks like a permanently high plateau." Two weeks later, stocks plunged off that plateau--not to return to their 1929 level for a quarter-century.

There was more to Fisher than those infamous words. The longtime Yale professor was a successful entrepreneur (he devised and marketed a precursor to the Rolodex), the author of a best-selling textbook on personal hygiene, one of the most prominent backers of Prohibition and a leading eugenicist (that is, he believed the human race could be improved through the weeding out of "degenerates").

More to the point, Fisher was the country's first great economist, a pioneer of the mathematical approach that came to dominate the discipline after his death. Fisher saw the behavior of the market in rational, mathematical terms. He wasn't completely doctrinaire about this--earlier in his career, he had allowed that investors sometimes behaved like sheep. But in the 1920s, convinced that skilled monetary management at the Federal Reserve and the rise of new, professionally run investment trusts had reduced the riskiness of markets, he lulled himself into believing that the prices prevailing on Wall Street were a reflection of economic reality and not of investor mania or a credit bubble.

Does this sound familiar? The financial history of the past decade is replete with echoes of Fisher's colossal 1929 miscalculation. A brilliant Fed chairman was credited with banishing panics and ushering in what economists called the Great Moderation. An explosion of financial innovation was deemed to have provided investors, corporations and banks with new ways of managing risk. Prices of stocks, houses and other assets rose to levels that were high by historical standards--but who was to say the market was wrong in fixing those high values?

In the 1990s and 2000s, in fact, this myth of the rational market was embraced with a fervor that even Irving Fisher never mustered. Financial markets knew best, the thinking went. They spread risk. They gathered and dispersed information. They regulated global economic affairs with a swiftness and decisiveness that governments couldn't match. And then, as debt markets began to freeze up in 2007, suddenly markets didn't do any of these things. "The whole intellectual edifice collapsed in the summer of last year," former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan said at a congressional hearing in October.

Well, maybe not the whole edifice. For all its flaws, Fisher's economic approach delivered genuinely important insights. He proposed in 1911 that the government issue inflation-linked bonds; in 1997, the Treasury Department finally got around to doing so. If anybody in power in Washington had been willing to follow his advice in 1930 or '31 (which essentially amounted to "Print more money"), the Great Depression might not have been so great. For the past two years, the Federal Reserve has been working right out of the Fisher playbook, and while the results haven't been perfect, they've been a lot better than those of the early 1930s. The economics that Fisher espoused--reborn after his death in 1947--should not be discarded. But clearly, there are some issues with it.