(2 of 3)

Another Bite at the Apple

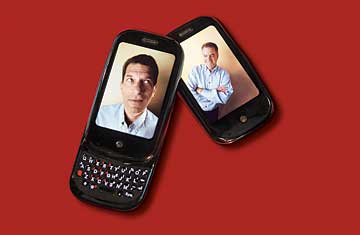

Rubinstein is a 30-year technology veteran who has worked at Hewlett-Packard and a variety of start-ups, including the legendary and doomed NeXT Computer, where he was wooed by Jobs. He arrived at Apple in 1997, about the time Jobs returned from exile and, as one of Jobs' trusted lieutenants, ran the hardware side of the company. The candy-colored gumdrop iMac he built helped haul Apple back from the brink. When Jobs decided that Apple should make a digital-music player, it was Rubinstein who discovered a tiny hard drive at Toshiba's research labs that would be the soul of the new machine: the iPod. (See the top iPhone applications.)

Then he burned out. Like others on the executive team, he had made a small fortune in Apple stock — $26 million by some accounts — and he didn't need to work anymore. What he wanted to do, he told Jobs at a meeting in the boss's office one September day in 2005, was build a house on the beach in Mexico, drink margaritas with his wife and toast the setting sun. Rubinstein told Jobs he wanted out. "He goes, 'Really?'" Rubinstein thunders, imitating a man in shock. Then he chuckles.

The meeting wasn't acrimonious, and he believed the door was open should he ever want to return. Jobs did not beg him to stay, and they worked out a plan for an orderly transition. Rubinstein went south and built his house, inventing a clever firefighting system that pumps water from the swimming pool (the closest fire department is 35 minutes away).

One day, "out of the blue," he says, he got a call from Fred Anderson, who had been Apple's CFO until retiring in 2004. It was Anderson who helped Apple figure out how to buy enough time to execute the turnaround. Anderson had had a terrible falling out with Jobs during the Securities and Exchange Commission's investigation of an options-backdating scandal in 2007. He settled the case without admitting wrongdoing but blamed the CEO for leaving him exposed. Not coincidentally, at about that time, Anderson joined Elevation Partners, a private-equity firm that had invested $325 million to buy a 26% share of Palm. (It now owns 34%.) Thinking that Rubinstein was just what Palm needed to right itself, Anderson introduced him to Ed Colligan, Palm's CEO. Colligan visited Rubinstein in Mexico and ultimately convinced him that Palm needed him to orchestrate a Jobs-style reinvention.

Seeing the Future in Palm

As he dug deeper, Rubinstein saw a pattern that intrigued him. Palm's first hit was the Pilot, which pretty much created the personal digital assistant (PDA). It enabled people to organize all their stuff on a computer, then sync it to the device. Handspring, Palm's successor in a convoluted corporate history, merged the PDA with a cell phone, but to Rubinstein it was sync that stuck out: "We looked at Palm's DNA and said, 'What made it great?' Synching — from Day One, Palm has been about synching." But these days, people don't want to be tethered to a computer, he says. "People keep their data all over the place. It's no longer spread all over their computer. It's spread throughout the cloud!"

Ah, the cloud, those enormous storage lockers of the Net that serve data — e-mail, pictures, video and your Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter pals — wherever you are. The problem is that all these data streams are increasingly hard to manage. I have one contact list of my friends and family on my iPhone; I can also switch to a directory of work associates. But then I've got a third list of friends at Facebook and yet another on LinkedIn. The promise of the Pre's WebOS is that it can take all those feeds and wirelessly combine them into one comprehensive contact list, without duplicates. On the Pre, this is known as Synergy, and it already works with contacts, e-mail, calendars and instant messages.