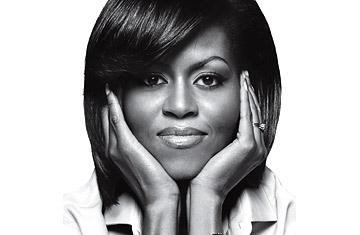

First Lady Michelle Obama

(5 of 7)

After Barack Obama was elected to the Senate, people asked Michelle if she'd be moving to Washington. "I was like, no," she says. "All my support is the support you build up over the years. It is my mom, girlfriends--you move away from everything." But when he won the White House, Michelle effectively moved her support system with her, not just her mother but old friends who are scattered throughout both the East and West wings. Other longtime Chicago friends are occasional visitors and joined the Obamas for spring break, as they have for the past several years--but this year the gathering took place at Camp David. Among the traditions is a talent show, with everyone required to perform. This year Michelle demonstrated her skills with two hula hoops; Obama and the men sang "You Are the Sunshine of My Life." The visits typically include charades, singing, board games--although now that the Obamas are making use of the White House bowling alley and pool table, the other families tease them by saying they'll refuse to play any games that the Obamas can practice in the new house.

As strange as White House life can be, it is providing Michelle a kind of balance she has seldom known. From roughly the time their first child was born, her husband was commuting to the state capital, the nation's capital or the campaign trail. Michelle all but charged him with abandonment, as he described in The Audacity of Hope: "'You only think about yourself,' she would tell me. 'I never thought I'd have to raise a family alone.'"

Winning the presidency was the ticket to at least one kind of normality. "Among the many wonderful things about being President," Barack tells TIME, "the best is that I get to live above the office and see Michelle and the kids every day. I see them in the morning. We have dinner every night. It is the thing that sustains me." The President refers to what he calls "Michelle time," when he takes a break during the day and retreats to the residence. Semiregularly, Michelle appears in the West Wing with the dog or their daughters for a brief but lively interruption. The family does "roses and thorns" around the dinner table, with all of them saying something good and something bad that happened to them that day. "And if the kids really, really need to see him, they can," she says. "They're free to walk in. They're welcome wherever they want to go around here." But they can also just ignore him, since they know he's around. "That's been terrific," she says. "It's more normal than we've had for a very long time."

Michelle's day starts at dawn, when she walks the dog and then hits the treadmill; she's had the same personal trainer for about 10 years, who has relocated to Washington from Chicago. There are no regularly scheduled meetings with her staff and never any meetings before the girls go to school. She tells aides which days she wants to be "on"; she can concentrate all her public events into a couple of days a week, leaving her free to sit in a lawn chair at the soccer field watching the girls play. Then there are the parent-teacher conferences, the play, the birthday party, the calls with parents to discuss the sleepover. "Kids force you into a normalcy," she says, "that, you know, it even trumps this [place] in some ways."