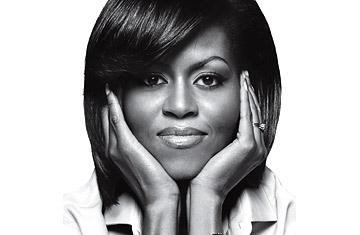

First Lady Michelle Obama

(2 of 7)

She admits that the sheer symbolic power of the role is perhaps greater than she anticipated. "I tried not to come into this with too many expectations one way or the other," she says on a sunny May afternoon in her East Wing office. "I felt like part of my job--and I still feel like that--is to be open to where this needs to go." She's always shown a shrewd eye for the strategic detour, suspending her career in favor of helping her husband get elected, then getting her daughters settled and her garden planted and, in the process, disarming the critics who cast her as a black radical in a designer dress. She will say she's just doing what comes naturally. But whether by accident or design, or a little of both, she has arrived at a place where her very power is magnified by her apparent lack of interest in it. "Over the years, the role of First Lady has been perceived as largely symbolic," Hillary Clinton observed in her memoirs. "She is expected to represent an ideal--and largely mythical--concept of American womanhood." That was not Clinton's favorite part of the job. Maybe this is Michelle's true advantage: she appears at peace, even relieved, that her power is symbolic rather than institutional. It makes her less threatening, and more potent at the same time--especially since her presence at the White House has unique significance.

The great-great-granddaughter of slaves now occupies a house built by them, one of the most professionally accomplished First Ladies ever cheerfully chooses to call herself Mom in Chief, and the South Side girl whose motivation often came from defying people who tried to stop her now gets to write her own set of rules.

Getting to Know You

Just a year ago, more people had a poor opinion of Michelle Obama (35%) than a good one (30%). During the primaries especially, she was too hot, and not in the way Maxim means it. She talked about America as being "just downright mean," and lazy, and cynical, how life for most people had "gotten progressively worse throughout my lifetime." Seeing an opportunity, conservative critics dubbed her Mrs. Grievance, called her bitter and anti-American, to the point that her husband had to defend her patriotism and call the attacks on her "detestable."

Her portrayal may have been a caricature, but it was also taking a toll. People who traveled with her from the earliest days in Iowa say she was a quick study, receptive to feedback on what was working and what wasn't. She began talking less about the country's problems and more about its promise. By the time the New Yorker parodied the parody of her as a machine-gun-toting revolutionary, she was reintroducing herself at the Democratic Convention as a wife, a mother, a sister and a daughter, listing why she loved her country and why her husband was the man to lead it.