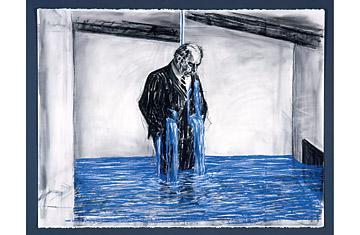

Felix Crying, William Kentridge, 1998-99

(2 of 2)

Each of Kentridge's film projects generates suites of charcoal drawings, most of them descendants of Goya's desolate readings of human affairs. Charcoal is exactly the right medium for Kentridge. Burnt carbon has a gravity all its own, and it's perfect for Kentridge's blasted landscapes, crowds of eternal refugees and monsters that could be the potbellied Will to Power. His world comes in shades of black, white and gray, with just occasional flecks of red or streams of bright blue that suggest water--a cool comfort against affliction but also the stuff of tears. In Felix Crying, a 1998-99 drawing taken from his short film Stereoscope, an inconsolable Felix stands in a rising pool of his own blue grief as it cascades from his pockets.

What are the sources of that grief? You might call it a nonspecific social and personal malaise. It was never Kentridge's way to tackle South African history head on. As a white South African, he once described himself as living at the "edge of huge social upheavals yet also removed from them." During the apartheid years, he didn't make propaganda films about the bitter fruits of the regime. Instead, he contrived melancholy parables about the psychological predicaments of life within a brutal and brutalizing system. You sense he's a man who would be happy to retreat into his own world if only the larger world weren't always drumming just outside his door. What James Joyce has Stephen Dedalus say in Ulysses--"History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake"--could be Kentridge's working motto.

Just as with the rest of us, his great weakness is hope. He's attracted to it and deeply suspicious of it all the same. It's a reason he's been preoccupied lately by the brief heyday of the Soviet avant-garde in the years right after the October Revolution, before Stalin put his very big foot down and imposed the rule of socialist orthodoxy in all artistic realms. A short episode of utopianism that ended in its own flood of blue tears, those years seem to epitomize for him the absurdity and paradox of politics.

Kentridge has borrowed from the imagery of that avant-garde, the ecstatic and utopian imagery of Vladimir Tatlin and Kazimir Malevich, for a production of The Nose--Shostakovich's 1930 opera based on the Gogol story about a Russian bureaucrat who awakens one morning to discover that his nose has left his body and begun to pursue its own career up the social hierarchy--that the Metropolitan Opera in New York City will mount next year. The San Francisco show, which was organized by Mark Rosenthal, a curator at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Fla., climaxes with a multiscreen gallery of films connected to that production. The nose climbs a ladder in silhouette (and tumbles down); a Cossack dances. On another screen are abject snippets from the 1937 trial transcript of Nikolai Bukharin, one of the multitude of old Bolshevik leaders devoured by Stalin. It's too soon to know how Kentridge will connect all this into a coherent production. But there won't be a diamond-crusted skull or a mirror-steel bling thing anywhere near it. That you can count on.

Steady Art Beat To read Richard Lacayo's daily take on art and architecture, go to time.com/lookingaround