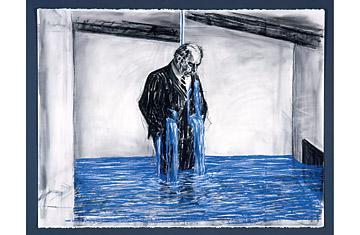

Felix Crying, William Kentridge, 1998-99

A lot of the most-talked-about art of the past decade or so was shiny, shrill and brazen. Damien Hirst's diamond-crusted skull, Jeff Koons' big mirror-steel bling things, Richard Prince's slutty-nurse paintings: they were all the swaggering output of a boom time. There were plenty of artists working in a different key, but no one could claim that anguished moralists were the representative figures of the age.

Does the financial collapse mean that a hushed and chastened mood will come upon the art world? Don't count on it. Remember how 9/11 was supposed to usher in the end of irony? That didn't happen either. All the same, is it too much to hope that a stricken world might have more time for art that's less declamatory and cocksure? If it does, this will be a very good moment for William Kentridge, anguished moralist.

Kentridge is a South African whose star has been quietly rising for more than a decade, years when his drawings and animated films made him a favorite of the art-festival circuit and he began designing opera productions in Europe and the U.S. But the sober-minded man we meet in "William Kentridge: Five Themes," a survey of his work that just opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and will travel to seven cities, seems especially pertinent these days. The question at the center of so much of his work--What do you do when the world breaks your heart?--is one that a lot of people are asking themselves lately.

Kentridge was born in 1955 in Johannesburg, the "rather desperate provincial city," as he's called it, where he still lives and works. His parents were both lawyers active in defending victims of apartheid. Their son took degrees in politics and fine arts from South African schools. For a time he tried acting. In the early '80s he studied mime and theater in Paris. But by the middle of that decade, back in Johannesburg, he had committed himself to art.

At the center of Kentridge's work are the hand-drawn animated films he started making in 1985. Some are intended to be viewed one at a time, like the mournful vignettes from the lives of his fictional alter egos: Soho Eckstein, a rapacious South African businessman, and Felix Teitlebaum, a melancholy soul who pines for Eckstein's sensuous wife. Others are produced as parts of multiscreen installations in which eight or more unfurl simultaneously on all four gallery walls. So in 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, his semicomical riff on the artist in his studio, we see Kentridge climbing a ladder on one screen (and tumbling down), pacing on another and ripping apart a life-size drawing of himself on yet another.

As an animator, Kentridge is a deliberate primitive. He makes his films by the painstaking process of drawing and erasing individual images, always on one sheet of paper, not successive sheets, so that the smudges and wipes survive from frame to frame and the images don't so much move as morph forward with bumps and stutters, the way they do in Claymation. Nothing could be further removed from the diamonds and stainless steel of the boom years. It's a style, poignant in its very crudeness, that by its simplicity confers instant legitimacy on Kentridge and his work.