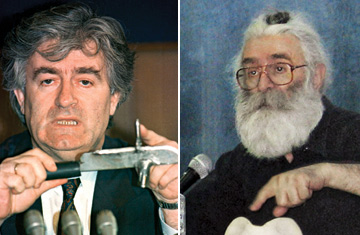

CHANGE OF FACE: Karadzic wielded steel and drew blood in 1992, left, but more recently he preached spiritual well-being as alter ego Dr. Dabic

(2 of 2)

A Litany of Horrors

The indictment, first drawn up in 1995, says that Karadzic, who presided — often grandly — over the self-styled "Serbian Republic" in eastern and northern Bosnia during the war, is responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Bosnian Muslims, as well as for a vicious ethnic-cleansing campaign that left many more homeless. The prosecution also claims Karadzic set up concentration camps in which non-Serbs were tortured, murdered and raped. The indictment was later amended to include genocide charges linked to the massacre of almost 8,000 men and boys in the U.N. "safe area" of Srebrenica in July 1995.

Karadzic has appealed his extradition, but is widely expected to be transferred soon to the Hague. In 2000, the prosecution reduced his indictment from an accumulated 36 counts to 11; Mirko Klarin, an observer at the Hague court since its inception, says it may thus make better headway than it did in the trial of Milosevic, who died without a verdict in 2006, four years after his trial opened. Klarin says the great bulk of the events for which Karadzic faces trial — including the Srebrenica massacre — have already been adjudicated in other cases. "The main problem will be to prove linkage [to Karadzic]," he explains. "The crimes have already been proved."

Belgrade, meanwhile, is awash with speculation about why it was Karadzic who got arrested and not Mladic. Serb security sources have indicated that it was by trailing individuals thought to be linked to Mladic that they happened upon Karadzic. (Rasim Ljajic, president of the National Council for Cooperation with the Hague Tribunal, denied reports that Western intelligence services had offered the telling tip. "We didn't need anyone's help in this matter," he says.)

While Mladic is thought to have sympathizers among circles connected with the former Yugoslav army, there is no reason to think he has any better protection among nationalists in the government or security services than Karadzic had. And his presence in Belgrade has been established at least twice: once in 2000, when he attended a football match, and again in 2003, when he underwent minor surgery in a Belgrade military hospital. Ljajic vows that Mladic is next: "We have just proved we're serious about war-crimes issues," he says. "We intend to finish the job."

Until they do, Serbia is not entirely off the hook with the tribunal. Mladic, after all, was physically present at Srebrenica on the eve of the massacre, and his indictment is every bit as damning as Karadzic's. Still, the Karadzic arrest has set a new tone in Belgrade. Says Natasa Kandic, a human-rights activist who has spent many years researching war crimes in former Yugoslavia: "This is a breakthrough moment for Serbia."

And not just for Serbia. When the wars of the Yugoslav succession began in June 1991, Luxembourg Foreign Minister Jacques Poos, with an eye to resolving them, famously declared: "This is the hour of Europe." It wasn't, of course. The brutal force of the combatants, especially those led by Karadzic and Mladic, made a mockery of feckless attempts by Europeans to broker peace. The circumstances of Karadzic's arrest, however tragically late, demonstrate far better the kind of benevolent power the E.U. can exert. Even if formal enlargement of the Union appears blocked for now, Karadzic's detention shows that in Serbia, the prospect of deeper ties to the West now outweighs the simpler lure of nationalism.

But oh, how long it took. And how many bitter memories still plague those who tend Bosnia's unquiet graves.

With reporting by Lauren Comiteau / New York