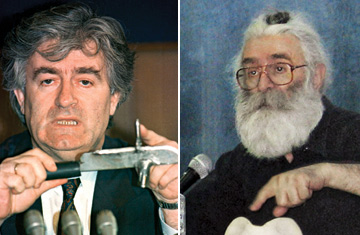

CHANGE OF FACE: Karadzic wielded steel and drew blood in 1992, left, but more recently he preached spiritual well-being as alter ego Dr. Dabic

Radovan Karadzic's last lair wasn't a cave or a safe house; no secret bolt-holes or special security details shielded him. Instead, the former Bosnian Serb leader, one of the world's most wanted men, was hiding in plain view amid the drab, anonymous housing blocks of New Belgrade, a suburb of the Serbian capital. He was nabbed not by NATO, whose forces had spent 12 years in a vain and sometimes desultory search for him, but by the security forces of Serbia — the country whose designs for grandeur he had so ardently tried to further. In the end, it seems, political will rather than operational cunning is the force that will bring Karadzic, 63, to a court in the Hague to face charges of genocide and crimes against humanity in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995.

Karadzic went to ground after the 1995 Dayton accords, which ended the Bosnian war, and was widely thought to have first based himself in the rugged mountains near the border of his native Montenegro. In the years since then, prosecutors at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia often complained that NATO and its associated intelligence services weren't trying hard enough to find Karadzic and his Bosnian Serb military commander, Ratko Mladic. Certainly no one has admitted to having had any inkling of Karadzic's final disguise: as a self-styled "spiritual researcher" named Dragan David Dabic.

"He was very convincing," said Vladimir Vukcevic, Serbia's special war crimes prosecutor. "He looked like a cross between Sigmund Freud and a beat poet," says Goran Kojic, the editor of the Belgrade magazine Healthy Life, for which "Dr. Dabic" wrote a column. The endless, often vile dilations on the dangers of Islam and the suffering of the Serbs that Karadzic peddled during the war seem to have segued into a snake-oil sales pitch for "personal auras" and "vital energies."

It's not karma, though, that caused Karadzic's arrest to happen when it did. For years, prosecutors at the Hague have considered the Serbian government more interested in protecting Karadzic and Mladic than in finding them. That changed in early July when the coalition government led by President Boris Tadic took power in Belgrade. Tadic had narrowly defeated hard-line nationalists at the polls on May 11, aided by promises from European Union leaders that Brussels wanted to open the door to Serbia's eventual accession — provided Belgrade cooperated in bringing Karadzic and Mladic to justice.

Tadic took that charge seriously. Just three days before Karadzic's arrest, the head of the Serbian security service, Rade Bulatovic, resigned; he was quickly replaced by a young and respected investigator, Sasa Vukadinovic. Bulatovic was considered an ally of former Prime Minister Vojislav Kostunica, a nationalist and staunch opponent of the tribunal. "I am sure that at least some parts of the intelligence community were involved in protecting Karadzic," says Milos Vasic, a security analyst for Belgrade's political weekly Vreme.

Whether Karadzic was accorded such assistance is only one of several outstanding mysteries. What's telling now in the Belgrade operation is who took the credit for finding Karadzic — and who did not. "We have just jumped over a big hurdle on the pathway toward European integration," said Defense Minister Dragan Sutanovac, a member of Tadic's Democratic Party. By contrast, the government's junior coalition partner, the Socialist Party of Serbia — once led by former Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic — was less effusive. Its leader, Ivica Dacic, heads the Interior Ministry, which pointedly denied that police had been involved in Karadzic's arrest.

Yet even among Serb nationalists, the Bosnian war is receding into history, relegated to Serbia's long catalogue of mythic losses. Aleksandar Vucic, the secretary-general of the ultranationalist Serbian Radical Party, said the arrest marked "a horrible day for Serbia." But the spontaneous demonstrations in Belgrade against Karadzic's arrest didn't approach the intensity of February's street violence over Kosovo's unilateral declaration of independence.