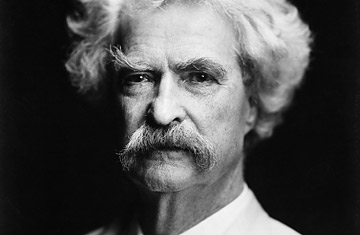

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, a.k.a. Mark Twain, pictured here circa 1900

(2 of 3)

Travel writing was lucrative, but novels were what serious literary men were expected to produce, and from the start Twain longed to be taken seriously, to be regarded as more than "merely" a humorist. So by 1873 he had rolled out his first novel, The Gilded Age, which he co-wrote with a Connecticut journalist, Charles Dudley Warner. With that book's title, Twain gave the post--Civil War era, a time of boundless greed and opportunism, the name it still has and that it shares, in some quarters, with the era we seem to be willy-nilly emerging from.

Once Twain found his calling as a writer and lecturer, success came quickly and abundantly. He may have been a critic of the Gilded Age, but he wasn't shy about taking on the trappings of a successful man. When the publishing royalties came pouring in, he built in Hartford, Conn., a big, ornate, financially burdensome house in a style that's been called "steamboat Gothic." It has been fully open to the public since 1974, but recently it has run into serious financial difficulties. A few years ago the group that maintains the house added an expensive visitors' center. Now it can't afford the upkeep, and there's a danger that the house will have to close.

To be honest, it's a spooky place--his favorite daughter died there, ranting and raving--and all the more worth preserving for that. I played billiards there once, on Mark Twain's table, with Garrison Keillor on his radio show. (Radio is a good medium for billiards because you can lie about how many balls you are sinking.) This is not the first time the house has been threatened by debt. That happened in 1891. Back then it was due to Twain's irrational exuberance. He had set up his own publishing company, which flourished for a while but eventually went under. Even before it failed, the Clemenses were compelled to leave the house and go traveling. (In those days, believe it or not, Americans could live less expensively in Europe than at home.) Then their finances got even worse. A marvelous new kind of typesetting machine that Twain had pumped a fortune into had ultimately proved unworkable. Eventually he owed creditors about $100,000, or roughly 2 million of today's poor excuses for dollars.

But Twain declined to let his admirers organize a relief fund. He resolved to make enough money himself, writing and lecturing, to pay back every cent. "Honor is a harder master than the law," he said, sounding considerably more righteous than usual. But it was actually his wife, supported by Henry H. Rogers, an otherwise ruthless Standard Oil exec who had volunteered to manage Twain's money, who insisted he not take an easier way out.

Twain mostly stayed abroad for the rest of the 1890s, establishing his celebrity in Europe and touring the world, making speeches and gathering material for his final, largely acerbic travel book, Following the Equator. When he returned to the U.S. in 1900, the Gilded Age was fading, but America was throwing its weight around internationally. Now Twain was not only solvent again but much in vogue--"The most conspicuous person on the planet," if he did say so himself. The renewed snap in the old boy's garters resounded around the world, as he took stands on American politics that, as his biographer Powers puts it, "beggared the Democrats' timidity and the Republicans' bombast."

The Spanish-American War of 1898 had met with Twain's initial approval because he believed that the U.S. was indeed selflessly bringing freedom to Cuba by helping it throw off the yoke of Spain. But the Eagle had also taken the Philippines as a possession, and by 1899 was waging war against Filipinos who were trying to establish a republic. "Why, we have got into a mess," Twain told the Chicago Tribune, "a quagmire from which each fresh step renders the difficulty of extrication immensely greater." The contemporary ring of that assessment is heightened by statistics. By 1902, when Philippine independence had been pretty much squelched, more than 200,000 Filipino civilians had been killed, along with 4,200 Americans.

As Twain got older and was beset by personal tragedies like the death of his beloved daughter Susy, his view of mankind grew darker. He once told his friend William Dean Howells that "the remorseless truth" in his work was generally to be found "between the lines, where the author-cat is raking dust upon it which hides from the disinterested spectator neither it nor its smell." But in 1900, when he could no longer stomach the foreign adventures of the Western powers, he came right out and called a pile of it a pile of it. In the previous year or two, Germany and Britain had seized portions of China, the British had also pursued their increasingly nasty war against the Boers in South Africa, and the U.S. had been suppressing that rebellion in the Philippines. In response, Twain published in the New York Herald a brief, bitter "Salutation-Speech from the Nineteenth Century to the Twentieth."

"I bring you the stately matron named Christendom," he wrote, "returning bedraggled, besmirched and dishonored from pirate-raids in Kiao-Chow, Manchuria, South Africa and the Philippines, with her soul full of meanness, her pocket full of boodle, and her mouth full of pious hypocrisies. Give her soap and a towel, but hide the looking-glass."

Later that year he published a long essay in the North American Review. It was called "To the Person Sitting in Darkness." The title was a biblical reference. The people in darkness were the unconverted, who had yet to see the blessed light. In fact, Twain pointed out, the problem was that they were seeing things too clearly. After years of exposure to Western colonialism, "the People Who Sit in Darkness ... have become suspicious of the Blessings of Civilization. More--they have begun to examine them. This is not well. The Blessings of Civilization are all right, and a good commercial property; there could not be a better, in a dim light ... and at a proper distance, with the goods a little out of focus."

The new century did nothing to improve his disposition. In 1901, U.S. President William McKinley was assassinated. His successor was Theodore Roosevelt, McKinley's 42-year-old Vice President, a blustery hero of the Spanish-American War whom Twain regarded as heedlessly adventurous in his foreign policy. "The Tom Sawyer of the political world of the 20th century," he called Roosevelt. Of course, Twain had been a great deal like Tom himself--as a boy, and as a man for that matter--but that was before becoming the conscience of a nation, "the representative, and prophetic, voice of principled American dissent," as his biographer Powers puts it.