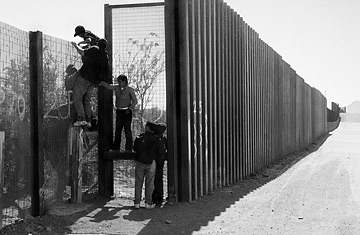

West of Naco, Arizona, some immigrants, including a 10-year-old boy, scale the new border fence in an effort to reach the States.

(3 of 4)

We were barely airborne at 6 a.m. when Dart got his first call, from a CBP agent asking for help tracking a group of northbound footprints. After nearly an hour of fruitless searching, Dart decided the walkers must have had a big head start. He peeled off to refuel. Along the way, we passed over dozens of abandoned cars and bicycles left behind by smugglers. Aloft again, Dart picked up word from CBP agents who were using four-wheel ATVs to track a large party of fresh prints. The newcomers were moving single file toward a mesquite thicket. From the air, it's extremely difficult to see a human being hidden under a tree, but having a helicopter overhead freezes walkers in place. The agents hoped Dart's arrival would pin down their quarry. So we circled for a while--until another agent radioed for help in finding a nefarious red car in the vicinity of a nearby crossroads. Dart banked toward the dusty village to perform a census of red vehicles. As the pilot headed back toward the thicket, his sharp eye spotted a flash of silver under some trees in a dry wash. Turning for a closer look, he found a clean, late-model sedan, slightly askew, apparently left in haste. Barely 10 a.m., yet it seemed the entire sector--a classic Western landscape of rimrock, saguaro and sage--was already swimming with fishy activity.

Meanwhile, the ATV team had reached the thicket. As always, the smugglers bolted, but agents Jeff Sargent and Samuel Estrada rounded up nine of their clients and were marching the group to a nearby road when Dart returned and set down his chopper.

The eight men and one woman appeared to be between the ages of 20 and 50. Sargent quizzed them in Spanish. They said they had crossed the border the previous morning, bound for Phoenix. From there, they had expected to disperse in search of work harvesting crops. They had covered some 25 miles (40 km) before being caught. Standing with their plastic jugs of water, a few meager supplies on their backs, they looked dazed by the array of force that had gone into their capture: the trucks, the ATVs, the radios, the guns, the bird. If they had been picked up in Yuma Sector, they would have been headed for jail. But there aren't enough courtrooms and cells to handle Tucson Sector's traffic. "They'll probably be on the bus back to Mexico by noon," Dart said.

Dart was busy all day. So busy, in fact, that it's hard to say honestly who controls the central-Arizona frontier. It's a no-man's-land where the law is only as real as the nearest cop. Dart took us to an ancient volcanic dome north of the border. It was nearly 40 miles (64 km) inside the U.S., but it was effectively the property of Mexican smugglers, who station spotters atop the hill. From there, a man with binoculars can monitor the movements of every CBP agent in the desert below. We climbed up and found a radio and a car battery to power it, along with garbage from countless meals--beer, soda, fruit cocktail, beans, tuna, sardines, coffee creamer--and blankets, sweaters, gas stoves and propane bottles. The spotters hide in caves on the hillside whenever a chopper flies by (they "rock up," in CBP lingo), but Dart said he had managed to catch three men there the previous month. By the next day, there were signs that a new spotter had arrived.

Even farther north, within sight of the Tucson suburbs, Dart took us to a wash where walkers dump their incriminating desert gear at the end of their crossing. Thousands of cheap backpacks littered the ground, as did countless soiled sweatshirts, water and whiskey bottles, toothbrushes and socks. Gesturing toward the city, Dart said, "Guide groups are buying $250,000 houses up there just to use as layups for these walkers. People who make their living at this are going to find a way through."

A Matter of Force The desert borderlands are ribbed with mountain ranges that go north and south without a care for national frontiers. Too rugged for Jeeps and fences, these areas can be secured only by boots on the ground. Steve McPartland leads one such force: the CBP's élite Air Mobile Unit operating out of San Diego. McPartland is a man of the world--born in Canada, raised in northern England and now an American citizen. After serving in the U.S. Army, he joined the border patrol 11 years ago. "Immigration was a natural for me," he explained, because having gone through the proper channels himself, he resented people who walk into the country illegally. McPartland's sector was the first to put up a border fence, as part of Operation Gatekeeper in the 1990s. Before that fence, San Diego Sector processed close to 1,000 captured illegal aliens on busy nights, but Gatekeeper cut that number while pushing illegal traffic into the mountains west of the city. The Air Mobile Unit was created to get teams of agents into the rugged countryside.

He told his story while climbing briskly up a ridge in the Tecate mountains of southwestern California, with their commanding view of nearby Mexico. The afternoon was hazy, and the hills were the colors of camouflage. Taking up his position, McPartland trained his binoculars south. He had pairs of agents deployed strategically over a couple of miles of the surrounding terrain. They would lie in wait until the walkers appeared, usually around dusk. As 6:30 p.m. came and went and all was still quiet, McPartland muttered, "Well, if they're not crossing here, where are they crossing?" Minutes later, he added, "I suppose I should be happy that it's quiet." As it turned out, that night was not completely quiet, but the fact remains that McPartland's piece of the border is tighter than it used to be. "What we've done down here works," McPartland told us. "If you have the right combination of personnel, infrastructure and technology, you can get it done."

But even as he spoke, he was worried about the impending end of Operation Jump Start. The two-year National Guard initiative expires on schedule this month, after Congress and the President turned down a request from the governors of California, Arizona and New Mexico to extend the program indefinitely. Homeland Security officials are hopeful that an aggressive recruiting program to increase the number of border-patrol agents will make up for the loss of the National Guard. But new agents don't arrive with their own choppers or bulldozer drivers. And it's risky to hire too many agents too quickly--as the growing number of corruption cases along the border attests. The bottom line is that resources are being pulled out of the border-security effort just as the fence is becoming a reality. That's why at one border-patrol station, agents made a wall calendar whose every page was May--so the National Guard's June departure date would never arrive.