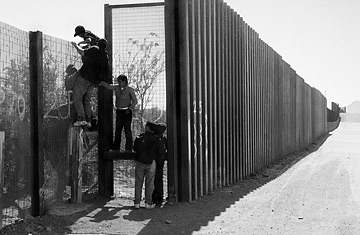

West of Naco, Arizona, some immigrants, including a 10-year-old boy, scale the new border fence in an effort to reach the States.

(2 of 4)

Something's Working Two years ago, Yuma Sector was the busiest jurisdiction in the entire border patrol. This 118-mile (190 km) stretch of border in western Arizona and eastern California was a well-known gap through which people and drugs flowed north while guns and money went south. The harsh desert on either side was crosshatched with smugglers' roads, trampled by the footprints of thousands of "walkers," some of whom dropped dead from thirst. In the city of San Luis, Ariz., so-called banzai runs were a near nightly occurrence. Scores of people would gather on the Mexican side and dash across a nearly open border toward the American neighborhoods. CBP agents could stop only as many as they could grab; the rest dodged past and melted into the city.

Then came the fence builders. Now a formidable triple barrier runs through town: three fences, the tallest 20 ft. (6 m) high, separated by floodlit corridors watched 24/7 by beefed-up patrols. Agent Eric Anderson, a three-year veteran, recalled a day in his rookie year when Yuma Sector nabbed 800 illegal aliens. "Some days now, we see zero coming through here," he said. East of San Luis, the triple fence becomes a double line, then a single tall fence, until it reaches the rugged Gila mountains. Beyond the range, the fence resumes, but now it's in the deep Sonoran Desert. The design here is steel posts, about 4 ft. (1 m) high, filled with concrete to thwart plasma torches and linked by surplus railroad iron. This fence is intended to stop cars, not walkers--but anyone crossing out here must be ready for a parched hike of 30 miles (48 km) or more, through cactus lands and bombing ranges, to the nearest road. That's a dwindling population, said CBP helicopter pilot Gabriel Mourik. "I used to catch 100 people in a day," Mourik said. "Yesterday, it was just one."

It is hard to describe how unwelcoming the western Arizona border is. The budget for replacement tires for Yuma Sector's four-wheel drives is $10,000 per week. Nearly every living thing either is venomous or has spines--or both--as we discovered when we spent two days at a CBP outpost called Camp Desert Grip. While exploring an ash-blackened waste of extinct volcanoes near the dead heart of the Sonoran Desert, we came across one of the many graves alongside a trail known as the Devil's Highway. Lava stones on the cindered earth spelled out 1871. Undisturbed 137 years later--that's how you know you've reached the middle of nowhere.

This desert is all about harsh juxtapositions--flat dust interrupted by sudden mountains; a delicate flower crowning a column of cactus spines. And now a new one, man-made: the sight of a smooth, new dirt road, huffing yellow construction equipment and mile after mile of reinforced steel. This, in a place that had never before seen a project more elaborate than a shack.

Critics complain that the fence is funneling migrants into a life-threatening desert, and they may be right, because while the area is difficult to reach from the north, on the Mexican side, Highway 2 parallels the border within sight of the U.S. It's tempting to catch a ride out here and start walking. Indeed, so many people have died or approached death in the Sonoran Desert that the CBP has installed radio beacons with flashing lights on them for walkers in distress to summon help. A more primitive sos is also common: a creosote bush set on fire at night.

Still, a case could be made that Yuma Sector's fence is part of an overall strategy that is actually reducing the number of unprepared humans wandering in the Sonoran Desert. As agent Ben Vik explained, by eliminating banzai runs in Yuma and reducing vehicle traffic in the desert, the fence has cut illegal crossings to a level at which the judicial system in western Arizona can actually handle the number of illegal immigrants apprehended by border agents. Instead of loading people onto buses and sending them back to Mexico--after which many immediately try crossing again--authorities are taking them to court. "Two weeks in jail with no income is a real deterrent," said Vik. This combination of forces--the fence, plus more agents, plus the desert, plus a real penalty--has allowed Yuma Sector to cut traffic 80%, the CBP estimates.

Tucson Sector: Wild, Wild West "Yuma has a lot of it controlled, thanks to the fence, but that has probably just funneled the action our way," said Chief Warrant Officer 2 Billy Dart, a chopper pilot in the Army/Air National Guard. His voice in the headset seemed far away through the muffled roar of rotors. In nine months of patrolling Tucson Sector as part of Operation Jump Start--which deployed National Guard troops to bolster border security--Dart has, by his rough estimate, helped stop "thousands of tons of marijuana, tons of methamphetamine" and countless human beings. It's no coincidence that the CBP's new busiest sector, in both human and drug traffic, is the one next door to Yuma. Crossings didn't stop--they moved.

There's a lot of fence going up here in central Arizona too, but conditions are less favorable along this 264-mile (425 km) stretch. In the sector's largest border town, Nogales, homes and businesses crowd so close to the border that nothing like the triple barrier in San Luis can be built unless buildings are bought and knocked down. Tucson Sector also has more paved roads through its desert, making it easier for walkers to reach pickup points. And there are more hamlets along its border. Smuggling is a major part of the local economy in Arizona towns like Naco, where the busiest saloon is decorated with a burlap marijuana sack and a sign for Coyote brand beer. (People who don't know that coyote is slang for a smuggler of illegal aliens won't get the joke, but then those folks have no reason to visit Naco in the first place.)

You don't hear many complaints about boredom from Tucson Sector agents. Lukeville is getting a double barrier, Dart explained, but "as fast as they put it up, on the southern side they take plasma torches and cut holes." There's a vehicle barrier south of the tiny town of Menninger's, but drug smugglers use hydraulic ramps to boost cars over for a quick dash into town. In the rolling pasturelands east of Nogales, the fence is a so-called Normandy barrier of crisscrossing railroad iron. Smugglers like to cut this fence with torches, then carefully put everything back in place so the border patrol won't notice. In parts of the sector there is still no fence at all. This includes a 28-mile (45 km) stretch near Sasabe where a multimillion-dollar pilot project to create a virtual fence of radars, sensors and cameras ended in failure earlier this year.