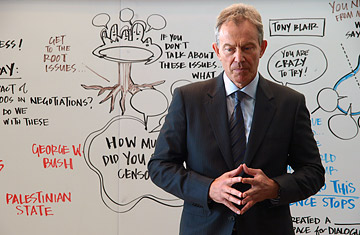

Tony Blair

(3 of 4)

In Cologne, Bono and his fellow Irish rocker Bob Geldof had an audience with Blair. Bono says that Blair was "the first head of state with whom we didn't have to argue that debt cancellation was not about charity, but justice." (Campbell remembers the meeting a little differently. Blair, he writes in his diaries, said debt relief was like Mount Everest. Bono replied, "When you see Everest, Tony, you don't look at it, you f___ing climb it.") I had breakfast with Blair in his hotel room the next morning, anxious to know how the talks on Kosovo had gone. In hindsight, I'd missed the key point of the weekend; in its Cologne communiqué, the G-8 countries committed themselves to debt relief, proof that a new and powerful alliance had been born.

Blair now wants to tap into the global links that have been built between development activists and people of faith. "Faith," he says, "can be a civilizing force in globalization," which will doubtless be the theme of the course on the topic that he will be teaching at Yale this fall. His foundation will seek to partner with organizations to advance the U.N.'s eight Millennium Development Goals adopted in 2000. Blair's first target is malaria, which kills around 850,000 children each year; many of these deaths could be easily avoided by prophylactic bedding. "If you got churches and mosques and those of the Jewish faith working together to provide the bed nets that are necessary to eliminate malaria," says Blair, "what a fantastic thing that would be. That would show faith in action, it would show the importance of cooperation between faiths, and it would show what faith can do for progress."

In its work in support of the Millennium Development Goals, the foundation will use its funds--it aims to build up a war chest of several hundred million dollars--to work with others active in the developing world. Rick Warren's Saddleback Church, for example, uses church-based clinics to provide basic health care in Africa. (Warren will serve on the foundation's advisory board.) I spoke by phone recently to Ari Johnson, 25, a Harvard medical student now working in Mali, West Africa, with Project Muso Ladamunen, a small Washington-based organization, who made Blair's point for him. "We've seen how potent the involvement of communities of different faiths can be," Johnson says, describing an international fund-raising effort around the Jewish festival of Sukkot to raise bed nets for Mali.

But inspiring though such tales may be, Blair will not find his work easy. Religion is not an uncontroversial matter in the developing world--witness the Catholic Church's doctrine on abortion and contraception or the discrimination that women face in many Islamic societies. Moreover, in many nations, the legacy of the "war on terror" and the invasion of Iraq--both of which Blair is deeply associated with--have soured the environment for anything that looks even remotely like Western Christian proselytizing. That is why the foundation stresses that it hopes to work with groups from six faiths: the Abrahamic trinity of Christianity, Judaism and Islam, together with Buddhists, Hindus and Sikhs. But Blair's history as a partner of Bush--and hence the skepticism with which his good faith is held--means he has high hurdles to leap if he is to turn his fine words into action.

Coming Together

Blair says his foundation will try to ensure that faiths encounter one another "through action as much as dialogue." But the dialogue is important. In our conversations, Blair kept harking back to the idea that people of different faiths need to learn more about one another and understand where they can work in common. The alternative, he thinks, is that religious people will be tempted to define themselves in exclusion to others rather than in cooperation with them--with potentially disastrous results. Says Bono: "I think he wants to dedicate the rest of his life to decrying the concept of a clash of civilizations." Bono told me that Blair once gave him a copy of the Koran, at a time when Blair was reading a passage from the holy book every night to try to understand Islam better. Ibrahim Patel, a young Muslim from Chicago who is the founder and executive director of the Interfaith Youth Core, hopes Blair will bring a new dynamism to an interfaith movement that can sometimes seem to consist of the same people meeting endlessly to discuss the same issues.

One senses, however, that it is not just relations among faiths that Blair wants to influence. It is also the relationship between those who rejoice in their faith and those who think religion is something quaint, the stuff of history books. And here Blair's religious agenda intersects another of his concerns: the growing distance between U.S. and European attitudes toward the world.

Blair has enough old-fashioned British reserve to have his doubts about the way religion is used in the American public square. Whenever Blair was on a foreign trip, says a close aide, his staff had to find him a church in which to worship each Sunday--and then try to make sure that the press didn't learn of it. By contrast, says this aide, "Bush and Clinton are always photographed coming out of church holding a Bible." But at the same time, Blair insists that Europeans need to understand the importance faith has in American life--and recognize that in its all-pervasive secularism, it is Western Europe, not the U.S., that is out of step with much of the rest of the world. "Europe," says Blair, "is more exceptional than sometimes it likes to think of itself."

That is true. But it is also true that if Blair's foundation is to take off, it will need support from Europe--and especially from his home country--as much as from the U.S. That is by no means assured. By the time he left office, Blair was deeply unpopular in Britain, and not just because of Iraq; Britons were tired of what they saw as a government of constant spin, tinged, toward the end, with sleaze. Though Blair's successor, Gordon Brown, has seen his own popularity plummet, there is no sign yet that Blair's reputation in the U.K. has been rehabilitated.