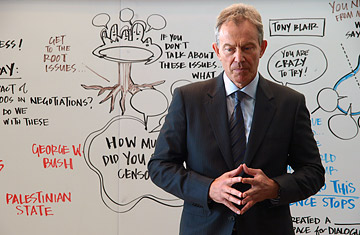

Tony Blair

(2 of 4)

For many Britons, the fact that Blair led them into a deeply unpopular war in Iraq is reason enough to question his sincerity. And the supposed "God is on our side" messianism of George W. Bush--Blair's geopolitical partner--is widely loathed in Britain. But long before Iraq or his association with Bush, Blair's faith was a source of something like contempt. For many in the British media, there is no fault worse than to be a sanctimonious "Creeping Jesus." During Blair's time in office, the satirical magazine Private Eye ran a regular (and very funny) column in the form of a parish newsletter, with Blair cast as the cloyingly earnest vicar of St. Albion church. Over the years, I have been struck by the vehement unwillingness of people in Britain to accept that Blair's faith is genuine or that it might provide genuine insights into our global condition. His religiosity was "incomprehensible," one well-known intellectual sniffed recently; I have heard Blair's recent conversion to Catholicism, a faith that has long had a following among posh Brits (think Brideshead Revisited), explained on the grounds of "snob appeal."

This is nonsense. Blair's parents were not churchgoers. But John Rentoul, Blair's first biographer, pointed out years ago that Blair's faith had been noted by those around him since he was a small child. Blair "rediscovered" his Christianity, he told me, while a student at Oxford in the 1970s. He was part of an informal late-night wine-and-cigarettes discussion group led by Peter Thompson, a charismatic Australian student and Anglican priest then in his 30s. (Thompson, who now lives in Melbourne, does not talk about his relationship with Blair.) I went up to Oxford just before Blair did; it was absorbed with sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll, with a sprinkling of student politics on top, and to espouse religion of any sort was to mark yourself as something of a freak. (My own family was deeply religious, something I successfully hid from my Oxford friends for years.) Those in Oxford's "God squad," Blair remembers, were at "the cutting edge of weirdism." Thompson, by contrast, Blair told me, was "an amazing guy--the first person really to give me a sense that the faith I intuitively felt was something that could be reconciled with being a fun-loving, interesting, open person." In 1974 Blair was received into the Church of England at his college chapel.

Blair's faith took on an extra dimension when he met and married Cherie Booth--like him, a young lawyer--after graduating. Blair's wife is a devout Catholic; not a posh Catholic, but a Liverpool-Irish, working-class, convent-educated girl with cousins who became priests. In her recent memoir, Cherie makes plain the centrality of religion to their relationship. Of the young Blair, she says, "Religion was more important to him than anyone I had ever met outside the priesthood." She and Blair would spend hours "talking about God and what we were here for. I don't think it would be too strong to say it was this that brought us together."

Their four children have been brought up as Catholics, and Blair has worshipped at Catholic churches for more than 20 years. But Britain, for all its secularism, is still nominally a Protestant nation with an established Protestant church; when Princess Anne's son Peter Phillips--11th in succession to the throne--married on May 17, his Canadian wife had to renounce her Catholicism. It was not until Blair left office that his long spiritual journey reached a destination that many had long anticipated, and he was received into the Catholic Church.

What Came Before

Blair says he converted to Catholicism to fully share his family's faith. But he plainly enjoys being part of a worldwide community with shared values, traditions and rituals. And why not? In a sense, the Catholic Church has long embodied the attributes of globalization that now engage Blair. Long before there were multinational companies, long before there were global ngos like Médecins Sans Frontières, long before there were international organizations like the U.N., there were religions--communities of faith with a global reach, whose adherents tramped from one end of the earth to the other, saving souls. To be sure, in their zeal to convert, missionaries often mixed faith with cruelty, as Spain's blood-drenched conquest of Mexico in the name of God abundantly proved. But as Nayan Chanda of the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization argued in his recent book Bound Together, the great religions were also intimately associated with the growth of trade and human contact. "For all the horror it visited upon people," wrote Chanda, "missionary activity had the effect of shrinking the world. The spread of proselytizing faiths brought dispersed communities into contact." Coffee, for example, traveled with Islam (which forbade the consumption of wine), spreading from Yemen throughout the Arab world, then into Turkey and Europe. The constant back-and-forth of Buddhist scholars between India and China nourished the Silk Road as an avenue of commerce. Sometimes religious divines explicitly advanced the process of globalization long before anyone knew of the word. I collect maps of the provinces of China drawn by Martino Martini, a 17th century Italian Jesuit missionary whose exquisite cartography revealed China to the world--and, indeed, to the Chinese themselves.

In the past decade, however, this old connection between religion and globalization has been augmented in a surprising way. Faith-based groups and social activists, two communities that long treated each other with distrust, thinking themselves poles apart politically, have come together to tackle issues of global poverty and health. For once, you can date precisely when a movement took off: it was in June 1999 at the G-8 summit of industrial democracies, in Cologne, Germany. I vividly remember arriving in town, expecting debate to be dominated by a rehash of the Kosovo war, which had ended that week. But Cologne had been hijacked by tens of thousands of supporters of Jubilee 2000, a campaign to forgive debts owed by the world's poorest countries. With its roots in Europe's churches, Jubilee 2000 brought together, in a great ring around the city, hymn-singing, sandal-wearing nuns, teenage kids and veterans of progressive politics. As Bono of the rock band U2 puts it, the movement saw "activists, punk rockers and priests marching in step."