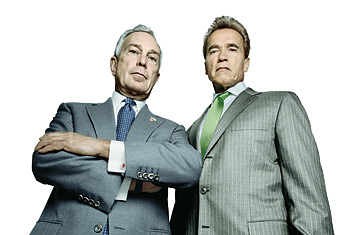

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger photographed together for Time.

(3 of 4)

To Bloomberg, Washington means gridlock, extremism and pettiness. It's the place where homeland-security funds were "spread out like peanut butter" for political reasons, so that rural states got more per capita than New York. And it's the place that's blocking him from cracking down on illegal guns. In 2005, after a rash of shootings, Bloomberg's aides told him that 90% of the illegal guns used in local crimes came from out of state and that 1% of U.S. gun dealers supplied 60% of its crime guns. And the Bush Administration had stopped tracking the problem; in fact, the GOP Congress had enacted NRA-backed language restricting federal officials from sharing gun-trace information with local police. Bloomberg appealed to Attorney General Alberto Gonzales but got the brush-off. So the mayor hired investigators to run stings in gun shops nationwide and sued 27 of the shadiest dealers; a dozen are now under court supervision. He also started Mayors Against Illegal Guns to fight the information-sharing restrictions; the group has recruited more than 220 mayors in a year, but Congress has not reversed the policy. "Ultimately, you have to blame the public," Bloomberg says. "They're not holding Washington accountable."

Politicians aren't supposed to blame the public. Or fly their own planes or pepper their autobiographies with sentences like "I dated all the girls." (He's now divorced with two daughters; he's dating New York's former banking commissioner.) But Bloomberg isn't typical. He's a press mogul who seems perpetually annoyed with the press. He broke with 200 years of tradition by rearranging city hall into a bullpen modeled on a trading floor, with his desk in the middle of 50 aides. (Perhaps transparency breeds loyalty, because his senior staff has barely changed in six years.) And now he wants to charge $8 to drive into busy parts of Manhattan on weekdays.

Bloomberg was initially skeptical of congestion fees because he feared the effect on outer-borough New Yorkers. But the data showed that few of them drive into Manhattan, and most who do will be served by the transit improvements the fees will subsidize. "What good is a 70% approval rating if we don't take risks?" he asked his aides. So far, that rating hasn't budged, which has given political cover to New York Governor Eliot Spitzer and even the Bush Administration to support his efforts to reduce emissions. "The naysayers who think global warming is too big a problem just don't have any vision," he says.

Arnold Alois Schwarzenegger has never liked naysayers: the ones who said bodybuilding would never be more than a cultish sideshow for musclebound freaks, the ones who said a Teutonic hulk with a long name and a thick accent could never be a movie star or the ones who said a Hollywood celebrity who announced his candidacy on the Tonight Show could never be Governor. But at about the same age Bloomberg was becoming an Eagle Scout, Schwarzenegger was in trade school learning to be a salesman. And he's used those skills to prove the naysayers wrong. "I'm a big believer in selling," he says.

His promotional genius helped transform bodybuilding into a lucrative business with a worldwide audience. And in Hollywood he was renowned for his intense focus on marketing and branding, if not for his dramatic range. He focus-grouped scripts and trailers; he honed his image through clever catchphrases and publicity campaigns. Critics mocked him, but he had a knack for giving people what they wanted, Red Sonja notwithstanding. "The successful star in the blockbuster era had to be a pretty good politician," Joe Mathews notes in his Schwarzenegger book, The People's Machine.

Schwarzenegger turned out to be a very good politician. He considered running for Governor in 2002, even though his only prior public service has been chairing President George H.W. Bush's fitness council. Instead, he decided to sponsor a wildly popular ballot initiative to fund after-school programs. The next year, when a fiscal crisis and an electricity crisis fueled an effort to recall Democratic Governor Gray Davis, Schwarzenegger jumped into the chaotic race to replace him. After a two-month campaign too quick to get deep into policy specifics, he had a new job in Sacramento.

If Bloomberg is a technocrat, Schwarzenegger is a populist; he's never stopped trying to give people what they want. In fact, he's never really left the campaign trail, spending much of his time pushing ballot initiatives. The most prominent was the stem-cell measure. The $3 billion referendum was a clear rebuke to President George W. Bush, and some Schwarzenegger advisers warned him that supporting it would alienate his Republican base. But he adopted the initiative as his own, named the Democrat who wrote it to be his top stem-cell adviser and became a global spokesman for California's medical-research industry.

"I like to do everything big," Schwarzenegger says. But he's not a superhero anymore. He's still got that incredible jaw, but he looks almost life-size, and he seems to have inherited Strom Thurmond's hair dye. He's still an enthusiastic salesman--everything is "fantastic" or "terrific" or "greatgreat"--but his constituents didn't want what he was selling in 2005, rejecting all four of his initiatives. He recovered in time to get re-elected by apologizing and reaching out to the Democrats who run the legislature. If the Bloomberg administration's symbol is the bullpen where the mayor manages, the Schwarzenegger administration's symbol is the smoking tent outside the state capitol where the Governor schmoozes while he lights up his cigar. "Our Founding Fathers would still be meeting at the Holiday Inn in Philadelphia if they wouldn't have compromised," he said in a blistering anti-Washington speech in February. "Why can't our political leaders?" He suggested that Bush should get himself a smoking tent.

Schwarzenegger made his most important compromise last September, when he signed a Democratic bill capping greenhouse-gas emissions. With his Hummers, his private plane and his conspicuous delight in conspicuous consumption, Schwarzenegger is an unlikely environmentalist, but he's become a global salesman for the war on carbon. His message, as usual, is that the naysayers are wrong: you can clean up the environment and still have a growing economy with big houses and big cars. He talks about green technology as California's next gold rush, its next Internet boom: "One plus one can make three!" He scoffs at environmental buzzkills who want Americans to drive wimpy cars and live like Buddhist monks. "Guilt doesn't work," he says. He sees the future in the Tesla, a hot new electric car that goes from 0 to 60 in 4 sec. His model cost a mere $100,000.