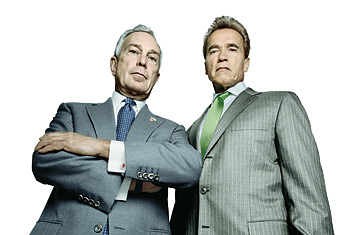

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger photographed together for Time.

(2 of 4)

So they're not exactly playing politics as usual. But their model of crossing party lines to act where Washington won't is increasingly common. As D.C. politics has become more of a zero-sum partisan game, mayors and Governors in both parties have taken on predatory lending, obesity, energy, health care and even immigration. "It's innovation by necessity," says Stephen Goldsmith, a former Republican mayor of Indianapolis who oversees Harvard's Innovations in American Government awards. This year hardly any federal programs applied. "Very unusual," Goldsmith says.

In the past, national policies often bubbled up from cities and states; think of the New Deal or welfare reform. It's especially common when cities and states enjoy surpluses, as they do now. And in the Bush Administration, domestic policy has understandably yielded to foreign policy. But it has also yielded to politics; even before Claude Allen was caught boosting goodies at Target, everyone knew Karl Rove was the real domestic-policy adviser. (Now the title belongs to Karl Zinsmeister--yes, the Karl Zinsmeister.) So while the Administration has embraced a few domestic issues--cutting taxes, promoting faith-based initiatives, requiring schools to test students, subsidizing prescription drugs and pushing (unsuccessfully) to restructure Social Security--its hacks have consistently outflanked its wonks. And while the new Democratic Congress has vowed to revive domestic policy, so far the only measure it has persuaded Bush to sign has been a minimum-wage increase.

Thirty states had already raised their minimum wage.

"Nature abhors a vacuum," says Bruce Katz, director of metropolitan policy at the Brookings Institution. "And the vacuum at the national level is immense."

As a boy in the Boston suburbs, Michael Rubens Bloomberg became an Eagle Scout. He later got an engineering degree at Johns Hopkins, where he learned rigorous thinking and data analysis, and a business degree at Harvard, where he learned that some credentialed élites weren't as smart as they thought. After graduation, he took a $9,000-a-year job as a Salomon Brothers clerk, made sure to arrive earlier and leave later than anyone else and worked his way up to partner. According to Wall Street legend, he used to brag that he could run the firm better than its leaders. In his 1997 autobiography, Bloomberg by Bloomberg, he said he didn't remember saying that, but he didn't deny it either.

After Bloomberg was ousted from Salomon in 1981, he used his $10 million payout to start Bloomberg LP, which now includes Bloomberg News, Bloomberg Radio and Bloomberg Television as well as the ubiquitous Bloomberg terminals that have served as the company's cash machines since they started appearing on desks everywhere financial information was needed. In his autobiography, he called his name "a synonym for success," describing his branding strategy thusly: "I was Bloomberg--Bloomberg was money--and money talked." In 2001, after the lifelong Democrat joined the Republican Party because the Democratic mayoral primary was too crowded, he self-funded his way to city hall. An endorsement from Mayor Rudolph Giuliani helped, but mostly, money talked.

Bloomberg inherited a tough situation. The city was hemorrhaging jobs after the Sept. 11 attacks, and Giuliani's second-term spending spree had left the city in a financial hole. Bloomberg raised property taxes 18% to attack the deficit, and he made some modest but politically difficult spending cuts, including the closing of several firehouses. He also engineered a hostile takeover of the city's troubled schools and banned smoking in the city's restaurants and bars. His approval ratings sagged into the 20s; his constituents booed him at parades. "They'll come around," he told aides.

They have, because the city has. Bloomberg hasn't etched his personality into the city's soul, but major crime has dropped 30% in New York in the Bloomberg era, without the racial antagonisms of the Giuliani era. Test scores and graduation rates are up, unemployment is at a record low, welfare rolls are at a 40-year low, construction is booming, the deficit has become a surplus, and the city's bond rating just hit an all-time high of double-A.

As a candidate with no political base, no political history and no political debts, Bloomberg came into office beholden to no one. Even when they don't agree with his decisions, New Yorkers seem to sense that he's set aside his conglomerate and his four vacation homes for public-minded reasons; his approval rating has hovered around 70% for nearly two years. His administration has made mistakes--an ill-fated stadium plan, a school-bus snafu-- but it's been scandal-free, and every major media outlet endorsed his re-election. Bloomberg likes to think big: as a businessman, he aimed to make financial markets transparent; as a philanthropist, he's funding research designed to eliminate malaria by building a better mosquito. "I was hired to solve problems," told TIME. "Yes, I'll fix potholes, but that's not why I wanted this job."

There's a good view of Bloomberg's problem solving from the roof of the 123-unit building Ken Haron just developed in Harlem. That neighborhood was once a national symbol of urban decay--drugs, violence, all the classic inner-city problems--but now its main problem is that it's so desirable, its housing is unaffordable. And in recent decades, the feds have stopped building subsidized housing. So Bloomberg has leveraged private money for a $7.5 billion effort to create 165,000 affordable apartments, enough to house the population of Atlanta. It's already one-third complete. Haron charges some tenants market rents of about $3,000 a month, but he has to reserve 80% of his building for lower-income families that won lotteries to pay as little as $700 for apartments with the same granite countertops. On the roof, Haron points out similar mixed-income projects in every direction: "That one's in the program. So is that one. That one's condo; it's ours too." Its penthouse is for sale for $1.7 million, but moderate-income families will pay $250,000 to live in the same building. "There's stagnation at the federal level, so we had to get creative," says Bloomberg's housing commissioner, Shaun Donovan.