(3 of 4)

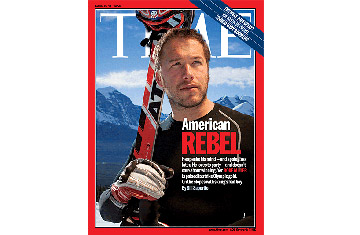

It's not that Miller, 28, was groomed for leading a movement. As a kid, he spent lots of time by himself, wandering the woods near his home. He didn't watch television because there wasn't one, which is generally coincident with not having electricity. That lifestyle was a choice made by his parents. His father Woody, a med-school dropout with no thirst for the professional life, found happiness working in the outdoors at a variety of hardscrabble jobs. His mother Jo worked at her father's sports camp. Miller has two sisters and one brother.

The Millers home schooled their children some years and sent them to the local school others. They lived so far off the beaten path that Bode had to trek through the dark woods to the bus stop. The many hours alone, he says, taught him to think. His parents were laid back, willing to let their children follow their own instincts. That led young Bode to the slopes of Cannon Mountain, an inclination that was no doubt heightened by his parents' split — although each of them lives in separate quarters at the family compound.

Miller's prowess as a skier and his reputation as a hard nut were already known in the area when he was offered a spot in Carrabassett Valley Academy, a prep school in Maine for ski racers. But coaches there couldn't tame him. They kept trying to alter his so-called back-seat style, and he resisted fiercely. If you want to ski on your ass, they finally told him, become a snowboarder. In his book, Bode: Go Fast, Be Good, Have Fun, he claims that another local coach even sabotaged his chance for the junior Olympic team. Then, when he was 19, a still unknown Miller skied his way onto the national team.

Experiences like those made him an iconoclast. He learned to appreciate the process of racing, not necessarily the result. And he learned to coach himself, because no one else could. You can hear the resentment in his voice today: "We should tell our kids to just have fun, participate and not get bent on winning or losing. But every coach, when they say that, they say it tongue in cheek, 'Don't worry about winning': If you win I'll get you ice cream, but if you lose I'm going to pout in the car."

At one point in his career, Miller's slalom-racing results could be summed up in three letters, DNF, as in did not finish. He seemed determined to either win or crash. But not from recklessness. He was in the process of changing his tactics. Simply trying to go faster wasn't working: correcting errors was harder, equipment didn't work as well. Instead, he figured that the quickest route down the mountain was the shortest route between gates. And that required deep analysis. "I needed to learn how to change directions and generate force that was different from other guys," he says. "I had to think about ankle torsion, where the screws are on the ski, how that affects the forces going into the ski and how the ski bends, your leverage points." He did not have to win. "It was a challenge. I was having the greatest time, making the mistakes, crashing. I didn't love racing to beat other guys. I loved it because it allowed me to do that exploring."