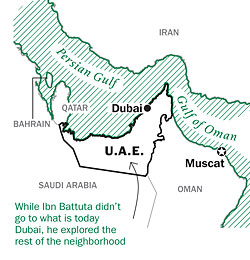

The Making of an Emirate

No one who has visited Dubai would be surprised that some crafty property developer has devoted an entire mall to the great Ibn Battuta. Its hallways may be lined with the H&M shops and food courts familiar to any New Jersey mall rat, but the complex has been designed in the spirit of Ibn Battuta's historic travels, or so its managers tell us. In the China hall, a life-size model of a square-sailed Chinese junk hovers over a babbling fountain outside the multiplex. The India section boasts an ornately decorated fake elephant. A few steps away, an exhibition educates shoppers about the explorer's achievements. Panels detail his exploits along his long journey, and an abacus and other paraphernalia of his time sit in plastic cases. In the middle is a Starbucks. Is this any way to honor the most famous of Muslim explorers?

Actually, it is. The mall may be tacky, but it is also a symbol of the Islamic world's quest to reclaim the economic grandeur it had in Ibn Battuta's age. The display by the Starbucks reminds us of the wealth the Arab lands possessed when he traveled through them. A century after the explorer's death, however, the Muslims' economic power began to wane, Europe came to dominate the global economy and the Islamic world never closed the gap.

Arab nationalists are quick to blame European colonialism for holding the region back, but that's a symptom of economic decline, not the cause. Others have pointed fingers at Islam's prohibition of usury, which, critics claim, hampered the development of modern finance. It doesn't fly. Muhammad was a merchant, and he chose Mecca, a city enriched by the caravan trade, to be the spiritual center for his new faith. For centuries, Islamic countries were every bit as economically progressive as Christian Europe.

In his new book, The Long Divergence, economist Timur Kuran argues that Islamic law is to blame. Its strictures on business partnerships and inheritance made it difficult for the Islamic world to match the institutions of capitalism forged in the West. While the Europeans reshaped the global economy with joint-stock companies and modern banking networks, the Islamic world never did.

In his new book, The Long Divergence, economist Timur Kuran argues that Islamic law is to blame. Its strictures on business partnerships and inheritance made it difficult for the Islamic world to match the institutions of capitalism forged in the West. While the Europeans reshaped the global economy with joint-stock companies and modern banking networks, the Islamic world never did.

That's what makes Dubai so interesting. In many ways, the emirate is an attempt to re-create the vibrant, cosmopolitan trading entrepôts that were once such an important part of the Middle East's economy. This has meant introducing institutions that make modern economies work. In 2000, Dubai launched a stock market. The government has set up special economic zones (SEZs) in which foreign investors can easily start businesses, and built a top-class airport and superhighways. Underpinning everything is a tolerance for foreign religious and cultural practices that has permitted people of all stripes to live and work freely. The lanky blondes in tank tops emerging from the gym at the Ibn Battuta Mall are a testament to that. "Dubai has the type of institutions and regulations in place that have brought it very close to competing with Frankfurt or Singapore," says Ayman Khaleq, a partner at law firm Vinson & Elkins.

As a result, Dubai has become the primary trade and finance hub in the region. Up from the sand dunes has risen a forest of modern skyscrapers, including the 163-story Burj Khalifa, the tallest in the world. The swish Capital Club is bursting with well-dressed bankers and private-equity specialists from around the world. The hallways of the Ibn Battuta Mall are a cacophony of languages, skin tones and clothing styles.

Yet despite its success, Dubai's transformation is far from complete. The sudden 2009 revelation that state-owned Dubai World (whose property arm built the Ibn Battuta Mall) couldn't pay its debts exposed a dangerous lack of transparency in the emirate's corporate and financial systems. That contributed to a property boom and bust that is dragging on the economy and testing the city's nascent bankruptcy law. The SEZs have been created by little more than the whim of Dubai's rulers — decrees that can just as easily be torn up. The economy is managed by an incestuous clique of local Arabs, each of them usually holding multiple posts among the city's banks, companies and government agencies. Ahmed Humaid al-Tayer, governor of the Dubai International Financial Centre, insists, however, that Dubai's leaders are committed to strengthening the city's institutions to create a healthier economy. "After the crisis, the government put emphasis on transparency and governance," he says.

The melting pot at Ibn Battuta Mall is also something of a mirage. The reality of Dubai society is darker: a privileged local elite lives off the labor of foreign workers with few rights. The locals are probably about a tenth of Dubai's 2 million people, but they control the government and enjoy all sorts of special perquisites, such as heavily subsidized electricity and water and free health care. Every company founded outside of the SEZs must have a local partner with majority ownership. Meanwhile, the rest of the population can stay only as long as their work visas remain valid. Many, therefore, feel like Bharat Butaney — who can't call home home. The India-born doctor arrived in Dubai in 1990 and can't imagine living anywhere else, but he worries that one day, his decades in the emirate might come to nothing. "I have given my youth for the development of this place," he says. "Say at 70, I'm told to go back to my country. How do I survive?"

The truth is that Dubai has been built by people like Butaney. There is nothing particularly Arab or Islamic about the Dubai success story. The majority of economic activity takes place outside Islamic law; most business is based on Western legal principles, not Shari'a. Dubai is not an example of an Islamic economy catching up to the West. It's a case of a Muslim country growing rich by copying the economic principles of the West.

Could Dubai have succeeded on Islam alone? We have no idea. There is no model that proves an economy built entirely on Islamic law can thrive in the modern world. It is true that Islamic finance is growing rapidly and becoming more complex, and some argue that the strictures of Islamic law are a much needed tonic for a world economy stricken with the fallout from financial excess. "There is a movement [in global finance] that you need to go back to basics," says Yavar Moini, an Islamic-finance specialist at investment bank Morgan Stanley. "One of the basic principles of Islamic finance is: Don't bet on speculation." But the steps needed to confirm that an investment adheres to Islamic beliefs add to costs. A real estate investor can't own a building with a whiskey company or pork brand as a tenant, and restrictions on debt tend to make Islamic investments heavier on equity than Western-style deals, adding to risk.

Still, Dubai has proved that an Islamic state can return to the glory days of Ibn Battuta's time by embracing the global economy and the tools to compete within it. If Ibn Battuta passed through Dubai today, he'd probably marvel at the shopping mall dedicated to his legacy, and take a seat at the Starbucks. But what would he make of a Java Chip Frappuccino?

— with reporting by Angela Shah / Dubai