Guarding the Loot A pirate in the Somalian town of Hobyo stands against the backdrop of a hijacked Greek freighter

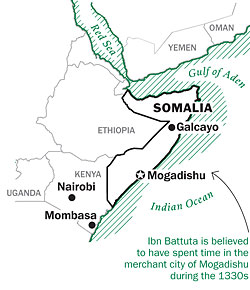

I have arranged to meet our pirate, somewhat incongruously, in the desert. I board a 1960s prop airplane that smells of goat and is piloted by four portly Russians. After a series of short hops across Somalia's northern wastes, we touch down on a red-dirt strip outside the town of Galcayo. The government in the capital, Mogadishu, doesn't control even half that city, let alone the hinterland, and the day before we arrive, seven people die in a gunfight in Galcayo. So at the airport, I hire eight men with AK-47s at $15 a day each, then drive across town to the high-walled aid-group compound where I'm staying. I am here to talk to a pirate king called Mohamed Noor, better known to his shipmates as Farayere, or Fingers. I want to ask Fingers why, when Somalia's pirates face an international armada at sea, when some 1,000 pirates have been arrested and scores more have died, piracy is still rocketing.

Fingers arrives alone. He is skinny and sun-creased for his 32 years. We introduce ourselves, tea is poured, and Fingers indicates I should start. How do you organize a pirate attack? I ask. There are no fixed pirate crews, Fingers replies. Instead, a few investors pool the money to hire two skiffs with fast outboards, employ five to 10 young men with guns — whoever shows up — and buy them enough food, water and fuel for a month. The investors then send their pirates out with orders not to return until they have captured a ship. That's it. Hundreds of pirates never return at all, says Fingers. Some drown at sea. Many more run out of food, water or fuel and die, starved and parched, adrift on the ocean.

"One time there was this group I knew that ran out of food and a guy died — and the other guys ate him," Fingers says, speaking in Somali through an interpreter.

"They ate their friend?" I ask.

Fingers laughs. "It's not a crime if you're about to die," he explains.

Fingers says he has invested in scores of pirate crews. I want to know about the ships he has captured and ransomed himself. In five years, he says, there have been two. The first earned him a split of $75,000, the second $280,000. Of that $355,000, he invested $50,000 in a money-lending business in Nairobi, the capital of neighboring Kenya. That still leaves more than $300,000, a sizable haul anywhere but a fortune in Somalia, the world's most failed state, a place that has been at war with itself for 20 years and where annual incomes are normally measured in the hundreds of dollars. Yet when I examine Fingers, I see no signs of wealth. He is squatting on the floor and is dressed like any East African deckhand: cheap thongs, a thin shirt and an old kikoi.

"Fingers," I ask, "where did all the money go?"

"Fingers," I ask, "where did all the money go?"

"Gone," he laughs.

"You spent it all?"

"I bought houses and cars. I bought a couple of Land Cruisers. I spent the money on friends. I enjoyed it. Now it's gone. That's why I'm still a pirate. I need the money. Besides, it's fun." Then Fingers shrugs and gives me a look that says: What did you expect from a pirate? Responsibility?

The Somalia Syndrome

straddling the trade route between East and West, the Indian Ocean has been a favored haunt for pirates for centuries, as pirate graveyards on Réunion and the Seychelles attest. But Somali pirates are a relatively recent phenomenon. When Ibn Battuta visited Mogadishu in the 14th century, it was the pre-eminent city of the Berbers and noted for its merchants and clothmakers — and Somalis would have been more prey than predator.

That's all changed now. Somalia hasn't had a central government since 1991. In some 20 years of civil conflict, the fighting has morphed from battles among local warlords and Islamist militias to war on the U.N. and the U.S. to, today, the African Union against al-Shabab, an affiliate of al-Qaeda. The chaos and lawlessness such a history implies inevitably reduce the chances of earning a legitimate wage and turn illicit trades like arms dealing, drug smuggling and piracy into industries.