An affluent passerby walks past a destitute man on a street in Hong Kong

(5 of 5)

In the long run, it is opportunity and not income that we should strive to equalize. It will not eradicate inequality. But

it will be an important step towards preventing it from growing further without compromising on

continued economic growth.

The 'ESLH Framework

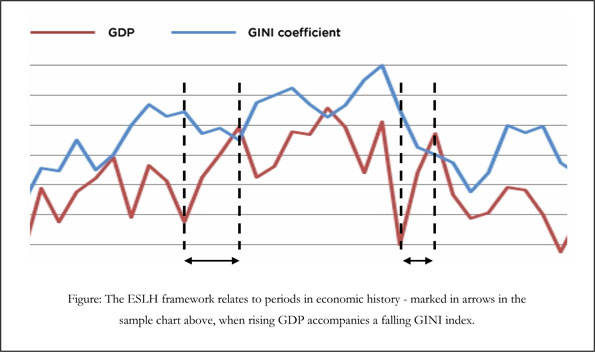

What remains then is for us to translate this idea of equality of opportunity into a set of policy guidelines. A detailed prescription of such recommendations is out of scope for this essay. Instead, what I would like to do is to outline a framework (let's call it the Economic Sustainability Lessons from History, or ESLH, framework) that can allow us to use empirical macroeconomic data from global economic history to pick out these guidelines ourselves.

Keeping in mind that any recipe for more equality that compromises on economic growth is unlikely to

be palatable to policy makers, investors or economists, the underlying idea of the ESLH Framework is to

hunt for instances in the history of developing nations where income inequality has fallen even as the

economy has continued to grow. Once identified, these windows of economic history can then be

studied further for specific policies that were designed to equalize opportunities and correspondingly

succeeded in equalizing incomes, while maintaining economic growth.

To see this framework in action, we can look at the example of Mexico. Between 1999 and 2008, Mexico's GINI coefficient fell 7 percentage points from 53 to 46, less than any recorded score for the country in the last 60 years. (15) In the same period, the country's real GDP continued to grow at an average rate of around 3%. (16)

What counsel can we draw from this experience? No doubt, the economies of Latin America and Asia are different, and there are things that worked in Mexico's favor that aren't applicable to Asia. But surely there should be a few ingredients of Mexico's success that can offer Asia a lesson in balancing economic growth with equality of opportunity.

There is at least one: the country's focus on rural development. A depreciation in rural poverty contributed significantly to Mexico's economic growth as well as its tempering inequality over the last decade. "Between 2000 and 2004, extreme poverty fell almost 7 percentage points, which can be explained by development in rural areas, where extreme poverty fell from 42.4 percent to 27.9 percent." 12

According to the World Bank, the factors that contributed to this reduction include "macroeconomic stability ... and the diversification of income from non-agricultural activities, such as tourism and services," arguably also applicable in equal measure in at least some parts of emerging Asia.

Gandhi said that India lives in her villages. Sixty-three years after the country's independence, his words are still true. Seventy-two percent of the country's one-billion-plus population today lives in rural areas. The same number for Nepal is 85%, Sri Lanka is 79%, Bangladesh is 76% and Pakistan is 66%. (13) For much of their history, these regions have formed the bread baskets for the rest of their countries. But with the rapidly declining share of agriculture in the GDPs for many of these countries, (14) it is imperative that there now be new avenues for development of rural territories, such as tourism as in the Mexican example above.

Bringing growth to the country-side, instead of luring village folk the other way with the glitter of swanky metropolitan development offers many advantages. It opens up new opportunities for the inhabitants of those areas without requiring them to desert their families or familiar landscapes. It reduces migratory pressures on urban centres, many of which in Asia are reeling from the effects of an exploding population density and an overburdened infrastructure. And it attracts more investment to the rural areas, allowing for economic growth to continue and at the same time be spread more evenly across communities.

Eliciting from the Mexican experience then, we have at least one strategic guideline that Asian leaders can follow in pursuing the goal of Inclusive Development: emphasis on rural development. There is of course no reason to stop at one. Following the ESLH Framework can allow for other such lessons to be learnt from economic histories of other countries as well that may be applicable in this region.

Conclusion

In many circles in emerging Asia, the recent financial crisis is already being talked about as history. A history that will teach us some lessons, but will not repeat itself, not in the immediate future at least. The future is bright. In the relentless journey of the Asia's economic bandwagon however, a growing number of its poor are being thrown off the cart along the way. Rising economic inequality now plagues countries across the continent's expanse, and threatens to undermine the very purpose that the polity of the region swears by: economic growth for its people.

It is essential for the long-term sustainability of this growth that Asian countries pursue a model of Inclusive Development, that offers a stake in the fruits of this progress to their poorest. The ESLH framework outlined in this essay helps us discover periods in our economic history when economic growth did not come at the expense of rising economic inequality, and learn from them. Nevertheless, this framework is but one step towards formulating an effective response. The key point is this — unless we are able to ensure that economic development creates new opportunities for each and every one amongst us, we may just be laying the stage for more men and women to give up hopes for a better future and resort to the business of selling paper tissues on street sidewalks.

Bibiliography

1. US economy back on track; IMF raises Asia forecast. Dated: October 29 2009.

2. "Analysis: IMF challenges Asia to change its economic habits." Dated: July 19 2010.

3. "'More poor' in India than Africa." Dated: July 13, 2010.

4. CIA - The World Factbook. South Asia - India. 5. "Study estimates China's rich hiding $1.4 trillion." Dated: August 13, 2010.

6. "Inequality in Asia, Key Indicators 2007, Highlights". Report by Asian Development Bank.

7. This claim is taken from the Wikipedia page for "Economic Inequality", which labels it as having been referenced from Wilkinson, Richard; Pickett, Kate (2009). The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. Allen Lane. pp. 352. ISBN 1846140396.

8. "Some Got Rich First — and Richer Later." Dated: May 2010.

9. "UN report reveals deep social divide in Thailand." Dated: June 23 2010.

10. This data was taken from the Wikipedia entry for "Kuznets curve", where it is marked as having been referenced from "the sources presented by Alice Hansen Jones (1775); Edward Wolff (1915-1995)."

11. Chapter 1: "Economic Freedom of the World," 2007. Economic Freedom of the World: 2009 Annual Report.

12. "Mexico: Income Generation and Social Protection for the Poor." Dated: August 24 2005.

13. People Statistics > Percentage living in rural areas. (most recent) by country.

14. "Rapid growth of selected Asian economies. Lessons and implications for agriculture and food security: Synthesis report." FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Dated: April 2006.

15. This data was taken from the chart "Gini Index - Income Disparity since World War II" on the Wikipedia entry for "Gini coefficient". The chart is an original work authored by user Cflm001 "from publicly available data from the World Bank, Nationmaster, and the US Census Bureau."

16. This data was taken from the chart "Average annual GDP growth by period" on the Wikipedia entry for "Economy of Mexico", where it is marked as having been collected from a set of 3 sources: i. Crandall, R (September 30, 2004). "Mexico's Domestic Economy". in Crandall, R; Paz, G; Roett, R. Mexico's Democracy at Work: Political and Economic Dynamics. Lynne Reiner Publishers. ISBN 10-1588263002; ii. Cruz Vasconcelos, Gerardo. "Desempeño Histórico 1914 – 2004" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-17; and iii. "IMF World Economic Outlook Database, April 2010". Retrieved 2010-07-24.

17. This chart is taken from page 6 (10 of 24 pages in PDF file) of 6.

18. This figure is taken from the Wikipedia entry for "Kuznets curve", where it is marked as being a "Hypothetical Kuznets curve. Empirically observed curves aren't smooth or symmetrical." The caption of the figure also includes a reference to the article "The Richer-Is-Greener Curve" for examples of "real" curves.

19. As in 15, these figures were referenced from the chart "Gini Index - Income Disparity since World War II" on the Wikipedia entry for "Gini coefficient." The chart is an original work authored by user Cflm001 "from publicly available data from the World Bank, Nationmaster, and the US Census Bureau."