An affluent passerby walks past a destitute man on a street in Hong Kong

(3 of 5)

Of a more immediate worry however, is the report's conclusion that rising inequality can impose

tremendous social costs, "ranging from peaceful but prolonged street demonstrations all the way to

violent civil war." So even as an economy develops, if it is unable to offer a stake in this development to

its poorest, it is only creating a recipe for more social tension. The report quotes a study that "suggests

that a 10 percentage point increase in poverty is associated with 23 – 25 additional conflict-related

deaths."

A separate study released last year drew a positive correlation between higher socioeconomic inequality and negative social phenomena such as "shorter life expectancy, higher disease rates, homicide, infant mortality, obesity, teenage pregnancies, emotional depression and prison population." (7) And if recent events are anything to go by, there is clear evidence that such phenomena related to economic inequality are increasingly their toll across the region.

Some commentators have linked the attacks on schoolchildren in China to the rising discontent among its poor and marginalized, "many of whom feel left behind as the rest of China gets wealthier." (8) Similar explanations have been offered for the groundswell of support behind the violence in Thailand earlier this year. According to the country's own Ministry of Social Development, the public protests in the nation's capital offered an opportunity to the country's most strapped citizens "to vent their frustrations over declining living standards and the deepening divide between rich and poor." (9)

Biggest Challenge

In breaking down the effects of rising economic inequality, I am perhaps missing out on a slew of others. Nevertheless, it is not the mere number of such repercussions that makes it the most significant challenge facing Asia today. It is the fact that very high (and rising) levels of inequality can make other problems worse.

To present a few examples, inequality makes it more difficult to address problems of ethnic or religious tensions (socioeconomic disparity has been credited for adding fuel to fire in the troubled southern Thailand), or uncontrollable population (rising poverty means more people without access to family planning) or even natural calamities (the greater the number of impoverished, the more the potential victims without the means to prepare for or rescue themselves from floods and earthquakes).

|

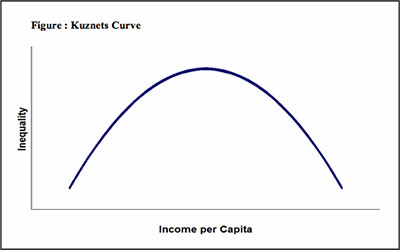

This theory is supported by data from the United States, where the share of wealth held by the top 1% of the society grew from 15% in 1775 to 45% in 1935, before falling back through the 1970's. (10) It could be that Deng Xiaoping had his one eye on these numbers when the then Communist Party leader launched market reforms in China in the 1970's with the famous words "Let some get rich first," (8) conceivably with the unspoken assumption that the rest will follow later.

What worked for America cannot however be expected work in Asia as well. This region is different; many developing countries here are more densely populated, which means that there are more poor who can band together in groups of sizeable clout, or be brought together by political parties with populist agendas, to demand for immediate action. In addition, the times have changed. With technology now connecting previously far-flung regions of a country, the underprivileged can now more easily gape at the affluence of their fellow countrymen, potentially inflaming their grievances even further.

Misguided Solutions

Waiting patiently therefore, for things to take their natural course as predicted by debatable economic theory, is not an option. Before discussing whether an alternative, affirmative approach can make a difference however, it will be helpful to take a detour and briefly look at the underlying causes of economic inequality. Figure Source: See 18