(4 of 4)

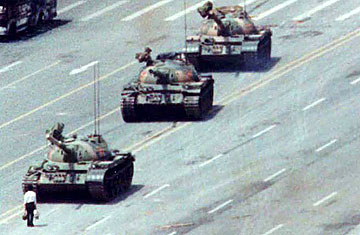

The origins of the Asian miracle lay in outward-oriented policies that encouraged integration of local manufacturing capacity with global supply chains, providing jobs for millions. China, above all, benefited from globalization, in more ways than one. After the Tiananmen disaster, China's leadership was lost and confused. It was not until Deng Xiaoping took his famous southern tour in 1992 that the policies of reform and opening up, which he had encouraged since 1978, got back on track.

That saved Communist Party authority. By providing a safety valve for discontent, China's boom helped sustain internal political stability. More than that: by linking the Chinese economy to that of the U.S., globalization contributed to global security, too. In classic models of international relations, it is easy to see how China and the U.S. might be rivals — one established power, one rising one, both with high degrees of national cohesion and purpose. But with every passing week, as another meeting between American and Chinese officials takes place, as more Chinese students study in the U.S. and more American businessmen travel to the Pearl River Delta, so the network of contacts between China and the U.S. grows in strength. These are societies that are coming to know each other well, and knowledge is the essential foundation for mutual trust and respect.

The second nonstate factor that has shaped the world since 1989 is the rise of religious extremism. This did not come out of the blue; Khomeini had taken power in Iran in 1979, while it was more than 20 years since the Six-Day War had both fueled a revival of political Judaism and led Arabs, dismayed by the failure of secular nationalism, to turn to Islam for succor. Still, most observers missed the significance of radical Islam in 1989. That was an avoidable mistake. Bedraggled Soviet troops had finally left Afghanistan in February, defeated not just by guns and Stinger missiles, but by a conviction on the part of those fighting them that they were engaged in a holy war against an infidel invader. With the benefit of hindsight, it was worth asking: What will those fighters do now? The answer would come soon enough, as radical Islam spilt out of its heartland and took the shape of international terrorism. The long and unfinished fight against terror since 2001 is abundant proof of how hard state powers have found it to confront those who are motivated by millennial religiosity, fighting asymmetric wars.

Third — and it goes without saying — technology has changed the world. By 1989, personal computers were commonplace in the West, while mobile phones, though they were as big and heavy as a brick, were becoming a status symbol. But in March, unnoticed by all but a handful of enthusiasts, Tim Berners-Lee, a British computer scientist working at the CERN laboratory in Geneva, sketched out the building blocks that enabled the Internet to become a ubiquitous tool of communication and information.

Increased computing power and the Internet have been the essential underpinning of globalization; without them, the logistics firms in Hong Kong who manage global supply chains would not be able to do their job. But more than that, they have shaken the power of the state in ways that traditional theories of international relations could not comprehend. At a time when China's online community rallied to defend a woman charged with killing a man she said was trying to rape her, and in which protesters on the streets of Iran used Twitter to get their message to the outside world, the disruptive, revolutionary power of technology in even the most autocratic societies has rarely been so evident. It will continue to grow.

We did not quite see that in 1989. But that's forgivable. As a news editor could have told you, in that extraordinary year there was a lot going on.