(2 of 4)

By 1989, all but the most calcified leaders in the communist world knew that at the most practical level — providing a decent standard of living to their people — their god had failed. The bluster of Soviet leaders who had once seemed to believe that the planned economies would bury the West had disappeared. A senior West German official once told me that the moment of maximum danger in the contest between communism and capitalism had come in the early 1970s, when the most efficient parts of the Eastern bloc were within sight of the worst-performing Western economies. But then in the U.S., Western Europe and Japan, the revolution in information and communication technology kicked into high gear, fueled by the sort of innovation, risk-taking and access to capital that the planned economies could never match. That gave a huge advantage to Western businesses over their Eastern counterparts. Surveying the pinched, stunted lives their people lived and the stores filled (and hardly that) with shoddy goods, Soviet leaders such as Gorbachev and Aleksandr Yakovlev, who had spent 10 years in Canada, knew that capitalism had won.

A Chinese Ricardo

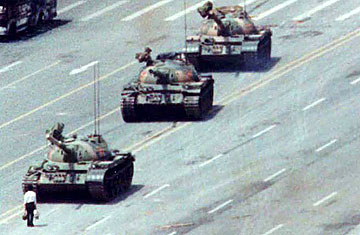

It was not just European communists who had come to that conclusion. Fukuyama noted that "anyone familiar with the outlook and behavior of the new technocratic élite now governing China knows that Marxism and ideological principle have become virtually irrelevant as guides to policy, and that bourgeois consumerism has a real meaning in that country for the first time since the revolution." In the newly released journals of Zhao Ziyang, an economic reformer who rose to become General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party before being ousted just before the Tiananmen massacre, there is a marvelous passage on the wonders of free trade. Zhao lamented that in Mao Zedong's China, "self-reliance" was "an absolute virtue. It became an ideological pursuit and was politicized." Only after reform, he continued, "could we take advantage of what we had, and trade for what we needed. Each place and each society has it strengths; even poor regions have their advantages." David Ricardo could not have put it better.

The broad consensus that free markets and free trade are the surest route to dispersed prosperity has survived the many modern crises of capitalism. The Asian financial meltdown of 1997 did not lead to autarky and dirigisme, but to an examination of the crony capitalism that had curdled the efficient working of markets. After the Internet bubble burst in 2000, investors in Western economies did not hide their savings under the mattress but ventured them in property and financial derivatives until the market popped again.

Not even the great recession of today has persuaded people to throw over the market system and choose state planning as an alternative. In the recent elections for the European Parliament — and Europe is supposed to be the part of the developed world that is least intellectually enamored of market capitalism — right-of-center parties did well. To be sure, from the U.S. to China, policy responses to the economic crisis have contemplated an increased role for the state. But there is an intellectual chasm between Keynesian stimulus packages and the temporary public ownership of bank stocks, on the one hand, and the assumption that the state can and should plan the economy on the other. Those who doubt it, and who think that the world (including the U.S.!) is going socialist, are too young to remember the sheer audacity of those who once thought that economies could be planned, or the miserable consequences of their belief.

Europe's Glory Lost

One consequence of the common policy response to the economic crisis has been the realization that, as UCLA history professor Peter Baldwin put it recently in Prospect magazine, the Atlantic is narrower than many have assumed. There are of course differences in European and American views of the world, especially in their attitudes to the use of force as a policy tool. For many Americans, the historian Tony Judt has written, "the message of the last century is that war works." With memories of their bloodstained recent past still fresh, few Europeans think that. George W. Bush, with a Texan swagger and the conviction of the born-again that God was on his and his nation's side, was distinctly unappealing to many Europeans. But Bush is no longer President; Barack Obama is, and anyone who can get 200,000 cheering Germans into the streets is someone to whom Europeans are happy to see their future linked with.