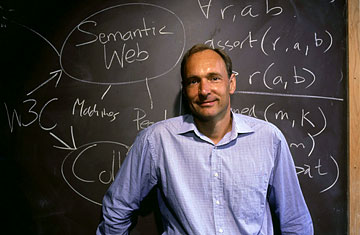

Berners-Lee is creating the next-generation Net

March, Geneva, Switzerland

I grew up reading Tom Swift Jr. stories. Looking back at the story of the Web makes me think it should be titled something like Tim Berners-Lee and his World Wide Web Machine. When Tim began his work with Robert Cailliau in 1989 at CERN, Europe's particle-physics lab in Geneva, the Internet was just beginning to emerge as a commercially available service. But it lacked standardized systems for formatting, storing, locating and retrieving information. Tim solved these problems by writing Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), a computer language for communicating documents over the Internet, and by designing a system to give documents addresses. He also created the first browser — calling it the WorldWideWeb — as well as a language (Hypertext Markup Language, or HTML) for creating Web pages and the first server software allowing those pages to be stored and accessed by others.

Like many people, I was completely unaware at the time of these historic developments. The Web first came to my attention in early 1993 when Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina released their graphical browser called Mosaic. It is hard to evoke the stunning impact Mosaic had on the community of Internauts who until that time were accustomed to text-based tools and keyboard navigation for retrieving content. The addition of imagery and magazine-like layout transformed the Internet into a gigantic publishing vehicle, an information-creation engine. It was as if a new guild based on new technology had been created in the Middle Ages; virtually every medium that had been invented in the past could now be presented through the Internet and users could interact with this information in ways no book, radio, television or newspaper could offer. The tsunami that flowed into the Internet via the World Wide Web also created the need for tools to find specific content in an ocean full of information. Thus were born a series of search engines and the giant companies such as Google and Yahoo! associated with them.

As with many inventions, once the conditions for their invention have been satisfied, many variations on a theme will emerge to interact, compete and evolve in a new universe. And like many other inventors I have known, Tim (now Sir Tim), is modest, passionate and committed to the further evolution of this universe. As the head of the World Wide Web Consortium at MIT, he continues to develop new capabilities for the Web. His passion these days is to find a way to reveal the content of huge databases on the Internet that are otherwise not visible to the search engines of today. This search for the Semantic Web has the potential to be even more significant than his invention of the World Wide Web. His success could open a new chapter in the history of information technology.

Cerf, known as one of the fathers of the Internet, is chief Internet evangelist at Google