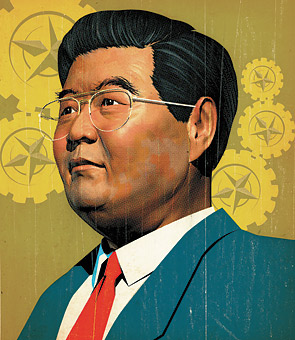

Right now, China, the most populous, economically dynamic and politically intriguing nation in the world, is on everybody's mind. As the Summer Olympic Games in Beijing draw nearer, China's role as industrial park to the world has been highlighted, brought into focus by product-safety scandals, environmental disasters and trade disputes. How can this infinitely complex nation be led? And what do we know about the man who leads it, Hu Jintao?

Not much. Hu, who became General Secretary of the Communist Party in 2002 and President of China the following year, has never granted a free-ranging interview. Nor has he cultivated the kind of flamboyant style with which his country became well acquainted in larger-than-life leaders from Chiang Kai-shek to Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. But politics in China has changed since the time of such giants. Competition within the Chinese leadership and a distrust of one-man rule have meant that Hu has had to lead by consensus. The fact that he is said to be patient and less ego-driven than his challengers has conferred on him a certain advantage. As the Chinese aphorism puts it, Tall trees attract wind. Someone who was more overtly ambitious might have lost his cool over challenges, but Hu has managed to convey an air of composure, the better to maintain a semblance of accord between fractious leaders.

So we would miss something important about Hu's leadership if we were to simply assume that his restraint was a sign of weakness. In reality, the way Hu has negotiated a difficult situation says much about him as a person and about his evolving and distinctive political philosophy. Even though China's revolutionaries spent decades trying to expunge "feudal" culture, Hu has ended up as something of a closet traditionalist whose sense of a political true north derives as much from the Chinese classics, to which he has turned in search of models of concord, as it does from Mao and Marx.

In February 2005, for example, Hu quoted Confucius to party officials, declaring that "harmony is something to be cherished." He and Premier Wen Jiabao regularly proclaim an aspiration to hexie shehui, or a harmonious society. And they often use another slogan, heping jueqi, or peaceful rise, a phrase designed to soothe foreigners worried about the double threat of China's fireball economy and rapidly modernizing military.

Such traditional-sounding rhetoric about harmony and peace — the antithesis of Maoist phrases about class contradictions and anti-imperialist struggle — has been spilling from party propaganda organs. Weary of struggle and strife, contemporary Chinese react almost autonomically to such rhetoric, which evokes the datong, the great harmony, a utopian ideal from the ancient Book of Rites. Hu hopes to attain a latter-day datong through what he calls a "scientific outlook on development," or a pragmatic refocusing on the challenges of poverty, social justice and the environment. Much of his political demeanor seems to suggest a yearning for leadership in the style of a Confucian junzi, or gentleman — one who governs by virtuous example and thus radiates benevolence throughout society.

How, in practice, Hu can use such classical nostrums to help him rule China is far from clear. Rebranding the office of the party General Secretary through rhetorical associations with the past is not guaranteed to help deal with Sudan, Burma, Taiwan and the U.S., never mind China's domestic challenges. Hu, says Yale historian Jonathan Spence, "uses a language that preaches caution and the avoidance of extremes, but seems to have little sense of how to implement changes that will boldly address China's formidable problems." Indeed, just beneath Hu's exhortations about harmony, peaceful rise and benevolent leadership, old Maoist structures remain. Far from wanting to weaken party control, Hu would like to reinforce it, to inspire officials to live up to the old ideals of "serving the people."

And it is important to remember that China's early philosopher-kings were not democrats. Indeed, the majority of them shared with Leninists a veneration for authority, discipline and orthodoxy. Confucius hoped that leaders would study the past to make the existing order more effective and fair, just as Hu would like to return China to some of the better ideals of socialism. Sipping at the well of the classics is a way for him to add a mantle of traditionalism to his rule and remain indelibly Chinese while avoiding any unsettling political reforms, much less a Western democratic path.

Trying to fully understand Hu, then, is like reading tea leaves. When once asked by an overseas journalist why he chose to remain so enigmatic, Hu said simply, "It's not fair to call me mysterious." But, mysterious or not, Hu, with his modesty, reserve and ability to balance contending forces, is, for now, serving China well.