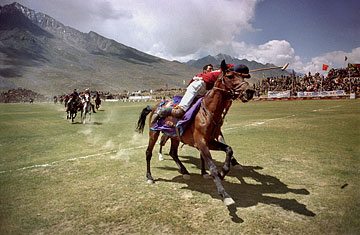

Full Speed Ahead

Racing for the ball during a match in Pakistan's Hindu Kush mountains

After he died, noble roll, a polo pony that once belonged to Asif Zardari, one of Pakistan's most powerful politicians, was buried under a house being built outside the capital Islamabad. That might seem an unusual, even macabre act. But Zubair Idris, owner of the house and inheritor of the pony, says that in a polo-playing family like his, it's tradition to bury under a new home an old, favorite mount that has passed away. Says Idris: "The house gets the strength of the horse."

So does its rider. In Pakistan, polo stands at the nexus of power and money. Long the province of the feudal landlords, who by virtue of their holdings could afford the strings of ponies required to field a team, polo is also the Pakistani army's preferred sport, a legacy of its cavalry origins. Polo ponies, stables, grooms and trainers are subsidized by the military. Officers, and their children, have access to one of the world's most expensive sports for the cost of a few rupees a month. Idris, a sixth-generation polo player, comes from one such family. The country's best players, if not military themselves, are descendants of military families. And for most of Pakistan's 60-year history power has been traded between the feudals and the military. Polo matches are where they meet. It is only inevitable that, in Pakistan, the game of kings is a kingmaker.

Riding High

No one, perhaps, better personifies the ability of polo in Pakistan to transport someone to the top than Zardari, scion of a small landholder and middling industrialist family who became Benazir Bhutto's consort in an arranged marriage in 1987. "When Zardari married Benazir, he had to do an instant social climb," says Idris. "Polo was the rocket that got him there."

After Bhutto first came to power in 1988, Zardari built stables and a polo field on the grounds of the Prime Minister's palace in Islamabad. He flew in horses from Saudi Arabia and Argentina. He imported the best coaches and horse trainers. What had once been the exclusive realm of feudal landlords and military men was thrown open to the new industrialists who flocked to Zardari's stables to curry favor with Bhutto's husband, who was also Minister of Investment. Zardari never became a great player — one old polo hand says he sat on a horse "like a sack of potatoes" — but even those cynical about his motives admit that he did bring polo back into the limelight. "It was good for us because it improved the breeding stock," says Idris. "Still, I'm sure he was less worried about our bloodlines than about his image."

Yet polo also hurt Zardari. When Bhutto's government fell under the weight of multiple corruption charges in 1996, Zardari's embrace of the élitist sport was held up as a telling symbol of excess. Though never convicted, he served 11 years in jail on charges of corruption (which he says were politically motivated, and have now been dropped). When Nawaz Sharif, Bhutto's political nemesis and successor, regained the prime ministership in 1997, he turned the polo field into a cricket pitch.

A History of Influence

Polo has always been more than a game. The name comes from the Tibetan for a bamboo root — even today some balls are still carved from the hollow bulb of the bamboo tree. Some 2,000 years ago (give or take a few centuries), Persian kings developed the sport as a training exercise for their cavalry, often setting scrimmages at a hundred horses a side. In many cases it evolved as a stand-in for war, the mock battles between tribes used to settle disputes that would otherwise end in bloodshed. Afghanistan's buzkashi, a variant played without sticks and using the carcass of a goat or calf, was similarly a substitute for fighting. By the Middle Ages, polo had conquered Asia and was played from Byzantium to Japan.

The warrior-emperor Aurangzeb chose his commanders from the polo pitches of Agra before expanding the Mughal Empire through the rest of the Indian subcontinent. During the Raj, British administrators transported polo home to England where a set of rules, handicaps and scoring regulations was applied, turning a rough warriors' game into a paragon of genteel sportsmanship before being exported back to the land of its origins. In America, polo turned the robber-baron Vanderbilts into New World royalty fit for rubbing elbows with the landed gentry of old Europe.

At the same time, polo is a great equalizer. The sport boasts only a few thousand professional players worldwide, and if not everyone is a personal acquaintance, their names are certainly familiar. "Polo is not a normal sport," says Tariq Afridi, Pakistan's ambassador to the Federation of International Polo. "Most players are fanatical; they do nothing but think polo. It's a world of its own, even internationally. We all speak a common language." Afridi, who started playing at age 12, carried his obsession through his career as a diplomat. He has played polo in every one of his eight overseas postings but Libya, and remembers competing against England's Prince Philip while a junior secretary in the Pakistani mission to France. The son of a soldier, he still marvels at the people he was able to meet. "These were people who in the normal course of events I would never encounter. It was an immediate entrée into a different world."

Most polo matches consist of four rounds of 71/2 minutes each. Given time for the mandatory change of ponies between rounds, the game is over in little more than half an hour. But, says Afridi, "you cannot imagine the hours of work that go into those 35 minutes. Each pony has to be exercised, groomed and fed every day. Then there is training, the vet and the blacksmith. And at the end of the day your favorite pony still ends up lame. From the minute you wake up you are caring for the ponies, and after the game you are making sure they are not lame. You have to be something of an obsessive to do this."

But each 35-minute match on the polo pitch makes up for the hours of backbreaking labor. As any golfer knows, the solid connection between club and ball vibrates through the body with the pleasurable hum of a struck tuning fork. Add to that the gratification of near-perfect communion between rider and horse, where each infinitesimal shift in weight or pressure of leg becomes an extension of thought. Combined with the synergy of four teammates pursuing an elaborate strategy, polo is the consummate union of action and intuition. Idris, who has played polo on and off for 30 years, says it is like playing chess at 40 miles an hour. "You are not just sitting on a horse whacking a ball around. In your head you are playing four moves in advance. It's all about anticipation, what your opponent will do and how your teammates will counter that move. But it is all taking place in a split second."

A Serious Player

Zardari's re-emergence in Pakistan's political scene — as co-leader of the powerful Pakistan People's Party, he could be in line for the prime ministership — has ignited a flurry of speculation among the polo-playing community that their passion might benefit from his fame and stature. But so far Zardari has stayed far from the pitch, too busy running the party he inherited from his wife. So busy, in fact, that he was unable to comment on his ponies or polo-playing, according to his spokeswoman. Idris muses on the hope and trust ordinary Pakistanis have invested in Zardari . "It's the same with the polo people, I guess. Everyone is hoping he just might surprise us with a planeload of thoroughbreds from Argentina." Noble Roll's spirit lives on.