(7 of 7)

Kennedy reached another visionary pinnacle on June 10, 1963, when—eager to break the diplomatic deadlock with the Soviet Union—he gave wing to the most poetic foreign policy speech of his life, a speech that would go down in history as the "Peace Speech." In this stirring address, J.F.K. would do something that no other President during the cold war—and no American leader today—would dare. He attempted to humanize our enemy. No matter how "profoundly repugnant" we might find our foes' ideology or system of government, he told the American public, they are still—like us—human beings. And then Kennedy launched into a passage of such sweeping eloquence and empathy for the Russian people—the enemy that a generation of Americans had been taught to fear and despise—that it still has the power to inspire. "We all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children's future. And we are all mortal." The following month, the U.S. and the Soviet Union reached agreement on the Limited Test Ban Treaty, the first significant restraint put on the superpowers' doomsday arms race.

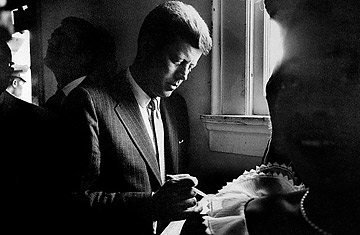

The speech that Kennedy was scheduled to deliver in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963, was to strike a similar peace chord. It was a courageous address to give in the Texas city, a seething hotbed of anti-Kennedy passions. Dallas had voted for Nixon in 1960 by the widest margin of any major city. It was the base of far-right agitators like General Edwin Walker, who after being forced into retirement by the Kennedy Administration, had launched a national crusade against J.F.K.'s "defeatist" foreign policy and "socialistic" domestic agenda. The day of the President's Dallas motorcade, angry street posters and an ad in the Dallas Morning News accused J.F.K. of treason. But Kennedy was undeterred. This is what he planned to tell his audience at the Dallas Trade Mart that afternoon: The most effective way to demonstrate America's strength was not to threaten its enemies. It was to live up to the country's democratic ideals and "practice what it preaches about equal rights and social justice."

Immediately after John F. Kennedy's death, he was wrapped in gauzy myths of Arthurian gallantry. In more recent years, he has suffered from a revisionist backlash, portrayed in books and the media as a decadent prince who put the nation at risk with his reckless personal behavior. Journalist Christopher Hitchens has gone so far as to dismiss him as a "vulgar hoodlum." While Kennedy's private life would certainly not pass today's public scrutiny, this pathological interpretation misses the essential story of his presidency. There was a heroic grandeur to John F. Kennedy's Administration that had nothing to do with the mists of Camelot. It was a presidency that clashed with its times and found some measure of greatness. At the height of the cold war, Kennedy found a way to inch back from the nuclear precipice. Under relentless pressures to go to war, he kept the peace. He talked to his enemies; he recognized the limits of American power; he understood that our true power came from our democratic ideals, not our military prowess.

He is still a man ahead of his time.