(3 of 3)

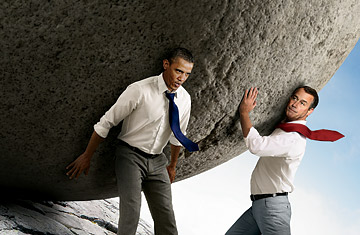

When Obama and Boehner presented their scheme to their colleagues at the White House — "almost like co-conspirators unveiling their master plan," one observer said — the initial response was good. Only House majority leader Eric Cantor and one other leader of the group of 10 expressed reservations. When that session ended, Obama called the Speaker and said he believed they were at a moment when they could reach across the divide and do something great. But in fact their grand bargain was already unraveling. Boehner no sooner got back to his office than he learned he was facing an insurrection on his right flank. He bet that the bill would be too big to fail, that it delivered the true change the freshmen so craved.

Turns out, he underestimated the purity of their ideology. Sure, they wanted the cuts, but with no pain or concessions from their side. The freshmen opposed anything that brought in even a dime more in taxes. Cantor, an ambitious majority leader who covets the speakership, told Boehner he believed such a plan could not pass the House. Meanwhile, Democrats weren't wildly enthusiastic about the deal either. Liberals were horrified that Obama had offered cuts in Medicare and changes to Social Security. House minority leader Nancy Pelosi, who had been shut out of the secret talks, drew a hard line. "I want to have full clarity about where House Democrats stand. We do not support cuts in benefits to Social Security and Medicare," she told reporters.

Behind the scenes, Boehner and Obama tried to salvage their vision. The Speaker called the President the next day to see if the Bush tax cuts could come off the table to keep his freshmen happy. Obama said they couldn't — that Republicans needed to give some significant skin in the game or the deal wouldn't fly with liberal Democrats. Late in the afternoon of July 9, Boehner told the President the deal was off. The votes just weren't there.

The Collapse

When compromise fails, the first reaction of both parties is to harden their positions. Boehner let it be known that the debt ceiling was Obama's problem, "and I think it's time for him to lead by putting his plan on the table — something Congress can pass," he told reporters on Capitol Hill. Other Republicans fell back to an ultimatum: Never mind, they said, no tax increases at all. Many, including 2012 presidential hopefuls Tim Pawlenty and Michele Bachmann, even argued that Republicans were elected to stop the debt ceiling from being raised, to force the government, however painfully, to live within its means. It served Obama's largest interest, as he strides forcefully back toward the center in advance of 2012, to continue to be the Reasonable Man. But then he tried to turn up the heat on Republicans by threatening to withhold Social Security checks in the event the debt ceiling was not raised by Aug. 2. The window of compromise had opened and then just as quickly closed.

The Republican refusal to consider any new revenues, including making easy fixes to the tax code to close loopholes for businesses and other groups that don't need public subsidies, is as recklessly absolutist as Democrats' insistence that bloated entitlement programs are untouchable. Both sides may be able to agree on a more modest package of nearly $2 trillion in cuts over 10 years in the coming days. One Democrat involved in the negotiations said both Boehner and Obama still see the advantages of going big. "Neither has changed his mind," he said. But as another veteran of backroom negotiations put it, neither side will give an inch until the last minute.

Washington works much more slowly now than it did 20 years ago — when it works at all. Its factions are more deeply divided; its muscle memory for give-and-take atrophied long ago. In the past, political leaders found the sensible center by knowing exactly what their rank and file would accept. That didn't happen here.

Boehner has warned his fellow Republicans that they would lose leverage as the Aug. 2 deadline for raising the debt limit approached. Already, 470 prominent business leaders have sent a letter to members of Congress calling a timely deal "vitally important."

"There are still a lot of people who want to just play this down to the wire," says one senior Administration official. "Our message is, Get this done. We're aiming to do as big a deal as possible, but we can't run the risk, any risk, that people think that there's any benefit in taking it right up to the wire."

But we're already at the wire. With just days to go, the stakes in this race have never been higher.