(2 of 3)

As uncomfortable as that experience was, the two men kept at it. They had little choice: to do nothing was to risk another financial crisis, brought on by rising interest rates, a possible credit downgrade and a potential run on money-market funds. All along Pennsylvania Avenue there were whisperings about finally getting serious, showing the world that America could get her house in order.

On April 13, Obama called on Congress to cut $4 trillion from the budget over 12 years. Though this was smaller than a plan to cut $6.2 trillion over 10 years, offered by Wisconsin Representative Paul Ryan, it was nonetheless an astonishingly large number for a Democrat. Then Boehner went to Wall Street and gave a fiery speech, saying Congress would raise the debt ceiling through 2012 but only if the White House agreed to offset the increase — to the tune of $2.4 trillion in spending cuts. This was genuine hardball: Republicans would hold the full faith and credit of the U.S. hostage to deeper cuts in federal spending. But it held the kernel of a deal. Instead of knocking down this offer, the White House was noticeably quiet.

The official Let's Make a Deal competition moved to Blair House, where both parties sent delegations in May to work out a compromise. The goals of this group, run by Vice President Joe Biden, were not modest: they would work out areas of potential agreement, looking at all government spending and tax loopholes. It was easy to get to $1 trillion; $2 trillion was much harder, especially since neither side came to the meetings united. The Democrats were acting like classically disorganized Democrats, one observer remarked later, "and the Republicans were acting like Democrats too."

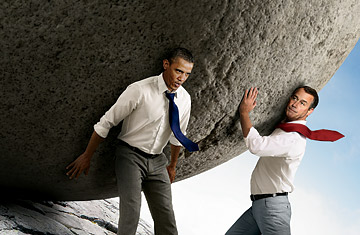

But the leaders, meanwhile, were acting like leaders. Only a President, elected to serve all the people, can do certain things — including reach out and lift up a friend or rival into the heady temple of Executive power. "I'm the President of the United States," Obama told Boehner. "You're the Speaker of the House. We're the two most responsible leaders right now." And so they began to talk about the truly epic possibility of using the threat, the genuine danger of default, to freeze out their respective extremists and make the kind of historic deal that no one really thought possible anymore — bigger than when Reagan and Tip O'Neill overhauled the tax code in 1986 or when Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich passed welfare reform a decade later. It would include deeper cuts in spending, the elimination of all kinds of tax loopholes and lower income tax rates for all. "Come on, you and I," Boehner admitted telling Obama. "Let's lock arms, and we'll jump out of the boat together."

After a round of golf at Andrews Air Force Base in mid-June, they retired to the clubhouse for drinks. Obama asked Boehner how they should get the deal done. They agreed to begin meeting together at the White House, alone, without aides. They would keep the talks private.

The first meeting came four days later, when Obama hosted Boehner on the Truman Balcony. They met again on July 3 on the President's Patio. The next day, as thousands of military families gathered on the South Lawn to watch the fireworks, Obama slipped away to call Boehner. They were now talking once a day or once every two days. When they spoke again on July 6, they were aiming for a $4.5 trillion down payment on the debt — much bigger than either side was discussing in public. Democrats would have to accept hundreds of billions of dollars in cuts to cherished entitlement programs like Medicare; Republicans would agree to close gaping holes in the tax code; both sides would work together to pass a separate measure to flatten tax rates by the end of the year (a plan that meant that taxes on the wealthiest Americans would go up). Obama was willing to consider slowing the rate of cost-of-living increases for Social Security as well. Both parties would have to swallow hard, but it was the grand compromise that had eluded Washington for two decades.