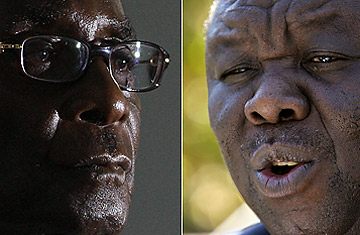

Robert Mugabe, left, and Morgan Tsvangirai

Despite their apparently intractable differences after a bitter and bloody three-month election process whose outcome has not been recognized by most of the world, Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe and the beleaguered opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) appear to be hinting that some form of power-sharing is inevitable. Mugabe remains defiant in the face of near universal condemnation of his regime's thuggish election tactics, and this week he stormed angrily out of an African Union summit that urged him to create a government of national unity. Still, Mugabe is expressing a willingness to negotiate and consider a unity government, perhaps mindful of the need to reverse his regime's growing isolation. And although MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai had warned that there would be no negotiations if Mugabe went ahead with the runoff vote staged last weekend, the opposition may be resigned to the reality that neither side in Zimbabwe's power struggle is capable of eliminating the other.

MDC spokesman Nelson Chamisa told TIME on Wednesday that although current conditions in Zimbabwe are not conducive to talks, in the interest of restoring peace to allow for fresh elections, his party will consider resuming dialogue with Mugabe's Zanu-PF Party in the coming weeks. "We now need to explore new ways of making sure we achieve free and fair elections," he told TIME. "This is why we have given the thumbs-up to a negotiated settlement." Zimbabwe's information minister Sikhanyiso Ndlovu made similar noises today, telling AFP that the "government is ready for dialogue with whoever." Mugabe had said on the eve of the runoff that he would begin talks with opponents "sooner rather than later."

Even as both sides express a grudging willingness to talk, neither appears likely to accept the other's terms for sharing power. Tsvangirai — who beat Mugabe in the first round of presidential balloting on March 29 — has said that he would consider letting the Zanu-PF leader remain head of state in a ceremonial capacity. But Mugabe and his backers in the security forces clearly believe they hold the best cards. Despite the widespread challenges to the legitimacy of his reelection, Mugabe had himself sworn in for a sixth presidential term on Sunday, before flying off to meet African leaders in the Egyptian resort town of Sharm el-Sheikh. But the Zimbabwean leader, more accustomed to being lionized as an African liberation hero, may have been surprised by the openly frosty reception he received from some leaders at the summit. Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga urged that Mugabe be suspended from the African Union, while Botswana's Vice President Mompati Merafhe said the Zimbabwean leader's presence at gatherings of African leaders would "give unqualified legitimacy to a process which cannot be considered legitimate." Delegates from Sierra Leone, Senegal and Nigeria also said they would not recognize Mugabe's presidency.

Even so, Mugabe retained enough support to ensure that the resolution eventually adopted by the African Union was conveniently vague, allowing plenty of room for preserving the status quo. And he made clear that he was not interested in replicating the deal that resolved Kenya's election crisis (which kept Mwai Kibaki in the presidency but made opposition leader Odinga the Prime Minister).

The reign of terror imposed by the regime's security forces and allied militia since the March 29 poll has made street protests or strikes an unlikely route to unseat Mugabe. The MDC's leverage is based largely on whatever pressure the international community can muster to change Mugabe's mind. Chamisa insists that the international community will have to be heavily involved in any negotiations with the regime. He said the MDC has been encouraged by the widespread condemnation of last week's runoff and hopes international pressure will eventually compel Mugabe to enter talks on terms more favorable to the opposition. France, currently leading the European Union, has made clear that Europe would only recognize a government led by Tsvangirai. "Previously, [Mugabe and his supporters] were standing on the African leg, but now that leg is artificial because Africa has spoken," Chamisa said. "We are not in reverse gear anymore. We are in forward gear."

Still, Mugabe and his circle show no signs of being ready to relax their hold on power. One basis for a face-saving compromise for Mugabe would be the fact that his regime has recognized that the March 29 poll put the opposition in control of Parliament. But rather than accept that as a basis for sharing power, analysts predict that the ruling party will work hard to sow discord between the MDC's two rival factions, which reunited only after the March 29 vote. And Mugabe's trump card remains his willingness to use violence against his citizenry. Even after the runoff vote, pro-Mugabe militias have continued to brutalize opposition supporters — the MDC says nine more of its supporters have been killed and hundreds more have been beaten and forced out of their homes since last Friday. "It's all very well to tell people to get into a government of national unity, but when there is violence on this scale, it's unconscionable," Zimbabwean human rights activist Elinor Sisulu told TIME. "The torture camps are still there, and people are still being driven out of their houses."

South Africa-based Heidi Holland, the only foreign journalist to have interviewed Mugabe in the past three years, fears that the purpose of the military mobilization since the March 29 election may not have been simply to ensure his victory in the runoff vote through intimidation, but also to punish voters for rejecting him in the first place. "The key to understanding Mugabe is his urge for revenge," says Holland, citing the forced eviction of some 700,000 suspected opposition supporters after the 2005 election. "He is emotionally incapable of accepting defeat."