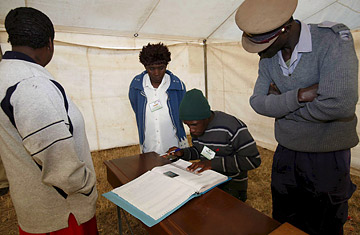

A policeman and voting officials check a voter's identity on the register at a voting station in Harare, Zimbabwe, June 27, 2008.

Under the watchful eye of the regime's security services, Zimbabweans Friday voted in a single-candidate presidential "runoff" that will almost certainly extend Robert Mugabe's rule until 2014. Despite reports of a low turnout, the decision by opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai to withdraw last Sunday makes Mugabe's victory inevitable. In Zimbabwe, presidential terms last six years, so by the time he faces reelection again, Mugabe will be 90 and will have ruled his country for 34 years. Nevertheless, expectations are that after six more years of hyper-inflation, mass unemployment and brutal repression, the President will be in better shape than his country.

This month, the United Nation's Food and Agricultural Organization listed Zimbabwe as one of four countries (the others being Lesotho, Swaziland and Somalia) worst affected by the world food crisis. Relief agencies say close to half the resident population now supplement their diets with food aid and, with an economy that has collapsed, there is little hope of improvement. Running parallel to Zimbabwe's worsening humanitarian crisis in the coming years will be a deepening political one, analysts predict. Pretoria-based Zimbabwe expert Chris Maroleng, of the International Institute of Strategic Studies, describes the three months since the first round of voting on March 29 — in which Tsvangirai came out ahead, but without the outright majority that would have ruled out a runoff — as a creeping military coup. The army, police and government-sponsored militias have fanned out across the country, killing, beating and displacing opposition supporters, wresting control of the media, electoral bodies and the judiciary and refusing to cede power even if the second vote were to somehow go against Mugabe.

That campaign of state intimidation will continue in the months ahead, says Maroleng. "After the poll, we will see a consolidation of the military junta's control of the organs of state. They have seized the state, and now they will want to stamp out any opposition to their rule." Facing a future of worsening poverty and harassment, millions more Zimbabweans are expected to flee their homeland. An estimated fifth to a quarter of the original population of 13 million are now refugees.

The world will express outrage at Zimbabweans' fate, and likely draw up stringent economic and diplomatic sanctions. But neither is likely to save Zimbabweans from their government — and that is proof of the end of an era. In 1999, the U.N. launched successful military interventions to stem bloodshed in Kosovo, East Timor and Sierra Leone. That was in keeping with a declaration the year before by then U.N. secretary-general Kofi Annan hailing a "new century of human rights." "No government has the right to hide behind national sovereignty in order to violate the human rights or fundamental freedoms of its peoples," he proclaimed. This collective world "responsibility to protect," as Annan's vision came to be known, fitted the mood of the age.

But several things happened since that have forced a retreat from those heady days: the U.S. war on terror gave intervention a bad name by associating it with big-power unilateralism; the crises got bigger — genocide in Darfur, famine in North Korea, a cyclone in Burma. Global competition also worked against global unity: China, for instance, blocked U.N. Security Council action against Sudan over Darfur to protect is oil concessions. Zimbabwe may have repugnant rulers, but it also has a consistent and grateful ally in South African President Thabo Mbeki and his fight against Western hegemony. Additionally, Harare has the world's second largest deposits of platinum, which assists its friendship with China. Kofi Annan's "responsibility to protect" was always a daring and ambitious idea. Six more years for Mugabe suggests it might also be as alive as Zimbabwean democracy.