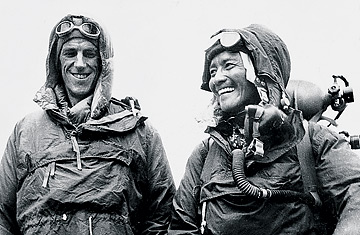

Edmund Hillary (left) and Tenzing Norgay were the first men to summit Mount Everest.

(2 of 3)

After school Hillary studied law for two years but dropped out to begin working full-time with his father as a beekeeper. Except for the last two years of World War II, when he served as a navigator in Catalina Flying Boats over the Pacific, Hillary was to remain an apiarist, in name at least, until 1970. He skied whenever he could and began hiking in the hills outside Auckland on weekends. As his climbing skills improved he visited the New Zealand Alps in the South Island, an impressive mountain range that reaches 3755m (more than 12,300 ft) on the summit of Mt Cook. "I didn't visualize myself becoming a renowned mountaineer," he explained later. "It happened gradually. Very few [people] suddenly decide they're going to be a world champion at something."

After the war the lure of the mountains grew stronger. In 1950 Hillary climbed in the Swiss and Austrian Alps and a year later joined a New Zealand expedition to the Himalayas. "I was very impressed," he recalled of his first view of the towering mountain range. "But the peaks didn't look all that different from what I'd been climbing in the Southern Alps [in New Zealand]." Though the expedition lacked funds, its climbers did well, conquering previously unclimbed 20,000-footers (6,000m plus). Hillary was quickly becoming known as a talented and aggressive climber. "I don't believe I was unpleasantly aggressive," he said later. "But I think I rather enjoyed grinding my companions into the ground on a big hill."

At the end of 1951 Hillary joined a British Everest Reconnaissance expedition and a year later was invited on another British expedition, this time to Cho Oyu, also in Nepal. The tall, gangling New Zealander, now 32, was reaching his peak as a mountaineer. "When you're younger you're probably faster, but when you're older you have incredible endurance," Hillary told Sports Illustrated 40 years later. "You also have a good deal more experience — especially of being uncomfortable and miserable, whereas the younger person who is all go, go, really hasn't been all that miserable in his life. When you're climbing at high altitudes, life can get pretty miserable. An older person is able to put up with this more easily."

Still, no team had managed to fuse the stamina and pace needed to conquer Everest. Many had tried. Between 1921 and 1953 eight major expeditions had attempted the climb, mostly from the north through Tibet. All had failed, with some 16 deaths. After World War II, several factors combined to make the climber's job slightly easier. With Tibet now locked behind Communist China, approaches from the north were impossible. To the south Nepal opened its doors to fee-paying Western expeditions, which discovered new, more accessible routes. Improvements in clothing and equipment, especially oxygen apparatus, helped dull the freezing temperatures and assisted breathing at altitude. And by the early 1950s Nepalese Sherpas — now experienced high-altitude climbers — had become essential to any successful Himalayan expedition.

Step by step, the summit grew closer. In 1952 Swiss climber Raymond Lambert and Nepalese sherpa Tenzing Norgay reached around 8,550m (about 27,100 ft) on Everest, the highest anyone had ever climbed. The following year a British expedition led by Col. John Hunt planned another assault on the mountain the Nepalese know as Sagarmatha — "head touching the sky" — and the Tibetans call Qomolangma — "the mother goddess of the earth." Hillary signed on. The 15-man team was one of the most professional assembled and, besides Hunt and Hillary, included Kiwi climber and Hillary's close friend George Lowe, Tenzing Norgay, known in Nepal as the "Tiger of the Snows," eight other British climbers, a cameraman, doctor and James Morris, a reporter from the London Times now better known as travel writer Jan Morris.

After preparations in England and Wales in late 1952 the expedition traveled to India and then on to Nepal. By early April 1953 they had begun establishing a succession of camps up Everest. In May they were ready for an attempt. Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans made the first assault on May 26, and got within 100m (about 300 ft) of their goal before being forced back after Evans' oxygen failed. Three days later Hillary and Tenzing set out in fine weather from their ridge camp at 8,500m (about 27,900 ft). At 11:30 a.m., after a five-hour climb, they reached the summit: 8,848 meters (29,028 ft) above sea level. "My initial feelings were of relief," wrote Hillary in Hunt's 1953 book The Ascent of Everest. "Relief that there were no more steps to cut — no more ridges to traverse and no more humps to tantalize us with hopes of success."

Success was theirs. Even before the expedition had reached base camp, news of their feat had made it to London — in time for Elizabeth II's coronation. Hillary, who had never approved of titles, learned to his horror that he had been knighted and could not demur as the title had been accepted on his behalf by the New Zealand Prime Minister. The euphoria of coronation and conquest combined as a symbol of a new Elizabethan era. In reality it was more an ending. Hillary and Tenzing's accomplishment was the last major earthly adventure and also the last great symbol of Empire. The next great exploratory leap came with a push into space by the new superpowers: the Soviet Union and the United States.