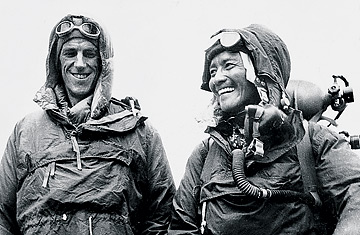

Edmund Hillary (left) and Tenzing Norgay were the first men to summit Mount Everest.

(3 of 3)

For New Zealand, with a population of less than two million, the achievement confirmed its proud place in the British Empire and marked an important step in its own course. "Everest A Crown Jewel" read the headline in Auckland's New Zealand Herald, "New Zealander Reaches Peak."

Hillary's passion for adventure remained undiminished. In 1958, as the leader of a support team to Vivian Fuch's planned crossing of Antarctica, he made a controversial dash by Massey Ferguson tractor to the South Pole, becoming the first person ever to reach it in a motorized vehicle. Hillary denied that he had raced Fuchs, arguing that once he was so close he felt he had to make an attempt. In 1968 he took a jetboat through the wild rivers of Nepal and in 1977 travelled up the Ganges, again in a jetboat.

Beginning in 1962 he began working with the Nepalese sherpas who had so often helped him. Raising funds through his Himalayan Trust, he helped install bridges and pipes, built nearly 30 schools, two hospitals, 12 medical clinics and two mountaineering clinics, restored monasteries, and planted more than a million seedlings in and around the towns of the rugged and poor Solu-Khumbu region of Nepal. Much of the last years of his life were dedicated to the work of the Trust, which opened offices in New Zealand, the U.S., Canada, the U.K. and Germany. Even into his 70s Hillary spent an average of five months away from New Zealand every year raising money through lectures and visiting the projects in Nepal. He still felt uncomfortable with his knighthood and fame but realized their advantages and the obligations they brought. "I would like to see myself not going [to Nepal] quite so often," he told TIME in 1996. "But at the moment... the responsibility is there. It has to be done." Determined to create a financial reserve for the Trust's future he was realistic about his role. "The worry is, What happens after Ed?" he said.

Involved in many of these projects were his family. He married New Zealander Louise Rose — a classical musician and the daughter of a past president of the New Zealand Alpine Club — in Auckland three months after returning from his Everest climb. A keen mountaineer herself she and Hillary regularly took their children Peter, Belinda and Sarah trekking in New Zealand as well as making family trips to Nepal, Australia and North America. Louise was as practical and down-to-earth as her husband. "[She] is an extraordinarily good sort of camping sort of wife," Hillary noted in Louise's 1973 book High Times of a family trek through Nepal.

In 1975, though, tragedy struck. Louise and Belinda were killed in an plane crash outside Kathmandu. "My life disappeared...," Hillary said. "I didn't believe that time would heal the loss." Life would always be different, he remembered later, but very slowly it began to mend. In 1985 Hillary became New Zealand's High Commissioner to India, Bangladesh and Ambassador to Nepal based in Delhi for four years. In 1989 he married June Mulgrew.

A conservationist before it was fashionable, Hillary became increasingly critical of the numbers allowed to attempt his famous climb — and the rubbish they left behind. "Everest, unfortunately, is largely becoming a money-making concern," he told a reporter in 1992, a month after 32 people had stood on Everest's summit on the same day. "If you are reasonably fit and have $35,000, you can be conducted to the top of the world." From the mid-1990s, expeditions and the Nepalese government heeded these criticisms and improved their efforts to clean up the mountains.

The famed Hillary stamina for high altitudes faded over the last few years. In Nepal he began catching helicopters to visit the higher projects, staying a few hours and then returning to base camp. Still, his sense of humor remained as dry and quick as ever. When asked, in 1996, if catching helicopters was frustrating after all his adventures, the answer came quickly and with a laugh. "No, no," he replied. "It's extremely comfortable." Not an overly religious man — the crucifix atop Everest was a favor for team leader John Hunt — Hillary struggled with various philosophies as a teenager before deciding that most religion was an escape from life.

He knew that Everest was the pivotal point in his life but was philosophical about its personal importance. "For me the most rewarding moments have not always been the great moments," he wrote in his 1975 autobiography Nothing Venture, Nothing Win, "for what can surpass a tear on your departure, joy on your return, or a trusting hand in yours?" Other things, he often said, had given him just as much pleasure.

Much of that came from his children. In May 1990 Sir Edmund — sitting in his study in the Auckland suburb of Remuera surrounded by shelves heaving with books and Indian and Nepalese statues and wall hangings — answered the phone to find his son Peter, on an expedition in the Himalayas, calling on a mobile phone. "Where are you?," the old man had asked. "Everest," came the reply. "The top of Everest." It was the sort of private moment Hillary enjoyed. He maintained that his image was largely a media creation. "I never deny the fact that I think I did pretty well on Everest," he told a reporter in 1992. "But I was not the heroic figure the media and the public made me out to be."

Once, while resting on a rock during a short trek in Nepal with friend and film director Michael Dillon, an American walker stopped and showed Hillary how to hold an ice-axe. "Hillary listened and thanked him, but said nothing else," remembers Dillon. "The American went away without any idea whom he had spoken to." The first man to stand on top of the world didn't see himself as a hero. Others always will.