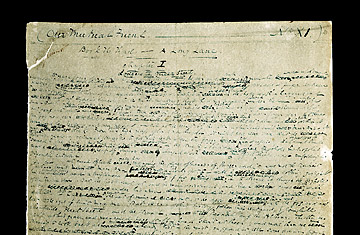

Image of the manuscript from "Our Mutual Friend" by Charles Dickens

(3 of 5)

Critics found these novels dreary and diffuse. Henry James, reviewing Our Mutual Friend for the Nation in 1865, wrote, "For the last 10 years it has seemed to us that Mr. Dickens has been unmistakably forcing himself. Bleak House was forced; Little Dorrit was labored; the present work is dug out as with a spade and pickaxe." But Dickens wasn't writing for the critics. His deft touch with comedy and pathos kept his loyal readers happy, and he had a new readership in mind: posterity.

His final bit of legacy building involved the appointment of his close friend John Forster as his biographer. When Forster's Life of Charles Dickens appeared, two years after the great writer's death, it included a tale that Dickens had been too ashamed to tell all but a handful of people: that as a child he had been sent for a time to work in a blacking factory while his father was in debtor's prison. Readers were stunned. They already knew the details but from the young David Copperfield, who speaks, with pitiful innocence, of being "thrown away" at age 10 by his cruel stepfather to labor in a warehouse. They knew that Amy Dorrit was born in the debtor's prison to which her father was consigned. They knew that Pip, the hero of Great Expectations, carries a lifelong burden of shame about his low origins. Until Forster's biography, they didn't know where all this shame came from. It was Dickens' last plot twist--the revelation that at his characters' most vulnerable moments, their creator was speaking from experience. It surprised his readers and kept him alive in their minds.

Immortal and Inimitable

The Dickens bicentenary--which is being celebrated worldwide with festivities ranging from art exhibitions to performances of his work to Twitter book clubs--coincides with another leap in literary culture: the rise of electronic text. The debate about e-books still focuses on the merits of page vs. screen. But the far more profound effect will be in disrupting the numbers game of literature--the game that began with the Victorian fiction boom, which began with Dickens.

E-books are changing the idea of being in print. Publishing was designed as a Darwinian process in which authors compete to be printed and then thousands of books go the way of the passenger pigeon. Digital files, self-publishing and print-on-demand technologies raise the possibility that this natural selection will be warped. "Our traditional definition of going out of print means that the content is no longer accessible," says Kelly Gallagher, a vice president of Bowker, a research firm that tracks the book industry. "The digital version lives in perpetuity." In some ways, that's a good thing--for writers, going out of print is a little taste of dying--but it exacerbates the problem of quantity. Yes, electronic books can linger unread, like any remainder hardback. But they are much easier to publish (and self-publish), store, circulate and revive. And copyright law, which always plays catch-up, will have to account for that.