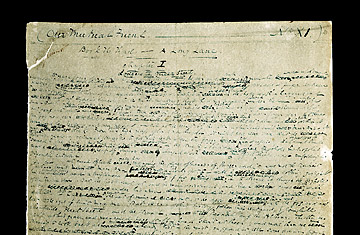

Image of the manuscript from "Our Mutual Friend" by Charles Dickens

(2 of 5)

Dickens' commitment to his audience also struck a contradictory balance: he cultivated a mass readership by creating a sense of personal intimacy. Readers felt he was speaking directly to them, and often he did. He channeled his thespian ambitions into live dramatic readings; his bloodcurdling performance of the brutal killing of Nancy in Oliver Twist caused fainting spells among audience members. "He invented that form of publicity," says Nicholas Dames, a Victorian scholar and chair of the English department at Columbia University. "He invented merchandising." (Think of A Christmas Carol, which he timed for the holidays.) "All those things that we associate with publishing culture--he was essentially the first." And Dickens knew it. He called himself the Inimitable, a nickname that stuck.

As his audience grew, Dickens took great care to keep his populist touch. Midway through the writing and publication of David Copperfield, he received a letter from an acquaintance objecting to a minor character, Miss Mowcher, who is implicated in a scheme involving the seduction of David's childhood friend Little Em'ly. Like the letter writer, Miss Mowcher happened to be a dwarf. Dickens responded that all his characters were composites and he hadn't meant to suggest that deformity of size might signify deformity of soul. But when Miss Mowcher reappears in the novel, he backpedals and clears her of any wrongdoing. It's an awkward, implausible scene, but Dickens cared more about appeasing his wounded reader. He felt responsible to her, and to all his readers, and they adored him in return.

As immediate as the response was to his work, Dickens knew that his writing was only as powerful as his ability to control it. Authors possessed limited copyright protection in England at the time his career began and virtually none abroad. American magazines pirated his work outright. Dickens fought successfully for stronger terms of copyright in England and for international agreements to prevent unauthorized translations and theft. He even advocated for an authors' union. As the editor of two weeklies, he was cultivating new talent--Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell--and he wanted writers to profit from their work, during and after their lifetime.

He also began to think posthumously in his fiction. His early novels were rooted in problems specific to his time: the Poor Law of 1834 (Oliver Twist), the abusive schools in Yorkshire (Nicholas Nickleby). As he matured, his criticism became more oblique. He invented grand, allegorical evils: the Circumlocution Office in Little Dorrit, the parasitic court case of Jarndyce & Jarndyce in Bleak House--giant grinders of corruption and inefficiency that mangled all who entered them. When people read Oliver Twist, they knew whom to blame and what to fix. With Dickens' later novels, says Dames, "You can't identify who the bad guy is anymore. Everything seems so systemic."