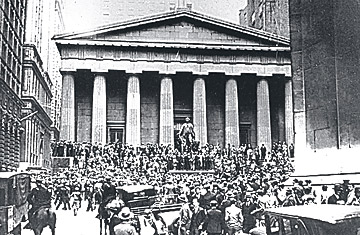

Stocks fell off what Irving Fisher had called a "permanently high plateau" in October 1929 and didn't return until that level until 1954.

(2 of 4)

Fisher fell on hard times after the 1929 crash--getting by thanks only to the generosity of a wealthy sister-in-law and his employer, Yale--and so did the myth of the rational market. For a few decades, financial markets were seen as unruly beasts that had to be tamed with tight regulation to help protect the hard-earned savings of regular Americans. But memories of the 1930s eventually faded, and in the 1950s, the idea that markets knew best began its comeback. This was part ideological reaction to the antimarket conventions of the day, part scientific progress. It was the combination of the two, in fact, that made the idea so powerful.

A key figure in the revival was the University of Chicago's Milton Friedman--and his libertarian ideological bent was certainly a factor. Friedman never believed markets were perfectly rational, but he thought they were more rational than governments. Friedman saw the Depression as the product of a Fed screwup--not a market disaster--and convinced himself and other economists (without much evidence) that speculators tended to stabilize markets rather than unbalance them.

But Friedman was a scientist too. During World War II, he used his mathematical and statistical skills to help determine the optimal degree of fragmentation of artillery shells. Officers flew back to the U.S. in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge to get his advice on the trade-off between the likelihood of hitting the target (the more fragments, the better) and the likelihood of doing serious damage (the fewer and bigger the fragments, the better).

Emboldened by this work, economists began to apply their number-crunching skills to the postwar market. Chicago graduate student Harry Markowitz devised a model for picking stocks that was, in Friedman's estimation, "identical" to his artillery-shell-fragmentation trade-off. And in the late 1950s, scholars at Chicago and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology became enamored of the idea that stock-market movements were, like many physical phenomena, random.

The two strands of statistics and pro-market ideology came together in the mid-1960s. It was the great MIT economist Paul Samuelson who made the case mathematically that a rational market would be a random one. But Samuelson didn't share Friedman's political views, and he never claimed that actual markets met this ideal. It was at Chicago that a group of students and young faculty members influenced by Friedman's ideas began to make the case that the U.S. stock market, at least, was what they called "efficient."

Their evidence? Mutual-fund managers failed as a group to outsmart the market, and studies showed that new information was quickly incorporated into prices. Eugene Fama, a young professor at Chicago's business school, tied all this together in 1969 into what he dubbed the efficient-market hypothesis. "A market in which prices always 'fully reflect' available information is called 'efficient,'" he wrote--and the evidence that such conditions prevailed in the U.S. stock market was "extensive, and (somewhat uniquely in economics) contradictory evidence is sparse."