If you're having a little trouble coping with what seems to be the complete unraveling of the world's financial system, you needn't feel bad about yourself. It's horribly confusing, not to say terrifying; even people like us, with a combined 65 years of writing about business, have never seen anything like what's going on. Some of the smartest, savviest people we know--like the folks running the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve Board--find themselves reacting to problems rather than getting ahead of them. It's terra incognita, a place no one expected to visit.

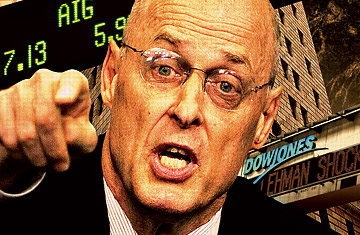

Every day brings another financial horror show, as if Stephen King were channeling Alan Greenspan to produce scary stories full of negative numbers. One weekend, the Federal Government swallows two gigantic mortgage companies and dumps more than $5 trillion--yes, with a t--of the firms' debt onto taxpayers, nearly doubling the amount Uncle Sam owes to his lenders. While we're trying to get our heads around what amounts to the biggest debt transfer since money was created, Lehman Brothers goes broke, and Merrill Lynch feels compelled to shack up with Bank of America to avoid a similar fate. Then, having sworn off bailouts by letting Lehman fail and wiping out its shareholders, the Treasury and the Fed reverse course for an $85 billion rescue of creditors and policyholders of American International Group (AIG), a $1 trillion insurance company. Other once impregnable institutions may disappear or be gobbled up.

The scariest thing to average folk: one of the nation's biggest money-market mutual funds, the Reserve Primary, announced that it's going to give investors less than 100¢ on each dollar invested because it got stuck with Lehman securities it now considers worthless. If you can't trust your money fund, what can you trust? To use a technical term to describe this turmoil: yechhh!

There are two ways to look at this. There's Wall Street's way, which features theories and numbers and equations and gobbledygook and, ultimately, rationalization (as in, "How were we supposed to know that people who lied about their income and assets would walk away from mortgages on houses in which they had no equity? That wasn't in our computer model. It's not our fault"). Then there's the right way, which involves asking the questions that really matter: How did we get here? How do we get out of it? And what does all this mean for the average joe? So take a deep breath and bear with us as we try to explain how financial madness overtook not only Wall Street but also Main Street. And why, in the end, almost all of us, collectively, are going to pay for the consequences.

Going forward, there's one particularly creepy thing to keep in mind. In normal times, problems in the economy cause problems in the financial markets because hard-pressed consumers and businesses have trouble repaying their loans. But this time--for the first time since the Great Depression--problems in the financial markets are slowing the economy rather than the other way around. If the economy continues to spiral down, that could cause a second dip in the financial system--and we're having serious trouble dealing with the first one.

The Roots of the Problem

How did this happen, and why over the past 14 months have we suddenly seen so much to fear? Think of it as payback. Fear is so pervasive today because for years the financial markets--and many borrowers--showed no fear at all. Wall Streeters didn't have to worry about regulation, which was in disrepute, and they didn't worry about risk, which had supposedly been magically whisked away by all sorts of spiffy nouveau products--derivatives like credit-default swaps. (More on those later.) This lack of fear became a hothouse of greed and ignorance on Wall Street--and on Main Street as well. When greed exceeds fear, trouble follows. Wall Street has always been a greedy place and every decade or so it suffers a blow resulting in a bout of hand-wringing and regret, which always seems to be quickly forgotten.

This latest go-round featured hedge-fund operators, leveraged-buyout boys (who took to calling themselves "private-equity firms") and whiz-kid quants who devised and plugged in those new financial instruments, creating a financial Frankenstein the likes of which we had never seen. Great new fortunes were made, and with them came great new hubris. The newly minted masters of the universe even had the nerve to defend their ridiculous income tax break--much of the private-equity managers' piece of their investors' profits is taxed at the 15% capital-gains rate rather than at the normal top federal income tax rate of 35%--as being good for society. ("Hey, we're creating wealth--cut us some slack.")

The Root of the Problems

Warren Buffett, the nation's most successful investor, back in 2003 called these derivatives--which it turned out almost no one understood--"weapons of financial mass destruction." But what did he know? He was a 70-something alarmist fuddy-duddy who had cried wolf for years. No reason to worry about wolves until you hear them howling at your door, right?

Besides a few prescient financial sages, though, who could have seen this coming in the fall of 2006, when things were booming and the world was awash in cheap money? There was little fear of buying a house with nothing down, because housing prices, we were assured, only go up. And there was no fear of making mortgage loans, because what analysts call "house-price appreciation" would increase the value of the collateral if borrowers couldn't or wouldn't pay. The idea that we'd have house-price depreciation--average house prices in the top 20 markets are down 15%, according to the S&P Case-Shiller index--never entered into the equation.

As for businesses, there was money available to buy corporations or real estate or whatever an inspired dealmaker wanted to buy. It was safe too--or so Wall Street claimed--because investors worldwide were buying U.S. financial products, thus spreading risk around the globe.

Now, though, we're seeing the downside of this financial internationalization. Many of the mortgages and mortgage securities owned or guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were bought by foreign central banks, which wanted to own dollar-based securities that carried slightly higher interest rates than boring old U.S. Treasury securities. A big reason the Fed and Treasury felt compelled to bail out Fannie and Freddie was the fear that if they didn't, foreigners wouldn't continue funding our trade and federal-budget deficits.