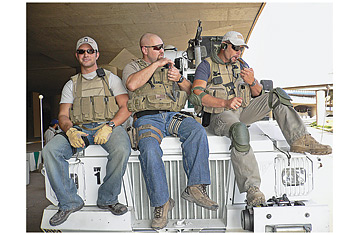

Blackwater contractors sitting on the Mambas at the terminal at Baghdad International Airport after a run, smoking a cigar and waiting for new team members to arrive.

Close to midnight last christmas Eve, a Blackwater security contractor named Andrew Moonen emerged from a boozy party in Baghdad's Green Zone and took a wrong turn on the way back to his hooch. There is as yet no satisfactory explanation for what happened next. An Iraqi guard named Raheem Khalif, who was protecting the compound of Vice President Adel Abdul Mahdi, was fatally shot three times. Time interviewed three Iraqi guards who were on duty that night and reviewed two signed witness statements: all say the shooter was a white male, wearing an ID badge typically used by security contractors. The day after the shooting, Moonen was fired by Blackwater and flown out of Iraq. His name was not directly linked to the incident until earlier this month, when a Seattle lawyer told the New York Times he was representing Moonen, 27, a former Army paratrooper, in connection with the investigation into the shooting.

The killing of Khalif barely registered outside the Green Zone. For Iraqis, it was just another in a long series of stories--stretching back to the early days of the U.S. occupation--about how private security contractors seem to operate with impunity in their country. Brought into Iraq because an undermanned U.S. military couldn't guard vital facilities and top American officials, contractors were armed with a decree by U.S. administrator L. Paul Bremer that made them practically exempt from prosecution under Iraq law). They quickly earned a reputation as cowboys: the kind that shoot first and never have to answer any questions afterward. As the number of contractors has grown, so has the volume and frequency of Iraqi complaints. A report by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform found that Blackwater alone has been involved in 195 "escalation of force" incidents since early 2005.

But these went largely unnoticed outside Iraq until Sept. 16, when a Blackwater security convoy shot and killed 17 civilians at a major traffic intersection in western Baghdad. The company claimed its men were responding to an attack on the convoy, but an investigation by the Iraqi Ministry of Interior the week of the shooting said the contractors had fired first. The incident sparked furor in the U.S., where it was seized upon by Bush Administration critics as yet more proof of botched planning of the Iraq war and the consequence of outsourcing too many military tasks.

Back in Baghdad, the Iraqi government briefly pulled Blackwater's authorization to carry weapons and gave the U.S. embassy six months to end all contracts with the firm. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice launched an internal review to determine if U.S. embassies are too reliant on contractors.

Guns for Hire

Blackwater has more than 1,000 men under arms in Iraq, but it is just one of dozens of security companies there. Across the country, there are now anywhere from 20,000 to 30,000 armed contractors, many of them performing duties that in previous conflicts were the domain of uniformed soldiers. Contractors are often the first line of defense on roads and at checkpoints to government compounds. They guard food and fuel convoys that supply the troops and protect embassies, aid workers and foreign businesses. Hundreds of contractors are based in the Green Zone, 4 sq. mi. (about 10 sq km) of riverfront buffered from the rest of Baghdad by concrete walls and manned checkpoints. Conversations with current and former guns for hire paint a picture of a world unique unto itself: insular, tribal, wary of the limelight, competitive and, for the most part, highly professional. The contractors--and they are almost all men--tend to be former soldiers and come from the U.S., as well as Britain, Ireland, South Africa, Nepal, Fiji, Russia, Australia, Chile and Peru. Their motivations vary from a thirst for adventure to a desire for a nest egg (or to pay down debt) to a refracted form of patriotism.

James Thornett was typical. The rugged 34-year-old fought in the invasion of Iraq as a British paratrooper. When the war ended, he left the military rather than take a quieter assignment. "I didn't join the military to sit at a desk," he says. "I joined the military to jump out of airplanes and fight." Seeking that excitement, he returned to Baghdad with Global Risk Strategies, a London-based firm that had set up security for the U.S. embassy. Thornett discovered that he liked Baghdad, and the money was "great"--contractors can make up to $12,000 to $33,000 a month. So he stayed on, switching first to Edinburgh Risk and Security Management, then to Aegis, both British firms. Then, for a change of pace, he set up a bar and restaurant in the Green Zone called the Baghdad Country Club, a popular hangout for contractors until it was shut down last May.

Not all contractors have Thornett's entrepreneurial instinct, and their lives in the Green Zone are far from plush. The typical contractor lives in half an aluminum trailer that has been reinforced with sandbags. The work is often dangerous, especially convoy duty beyond the concrete walls in what is known as the Red Zone.

Some security convoys keep a low profile, using cars and dress that blend into the bustling streets of the city. Others--especially Blackwater--"roll heavy" in large convoys of big, armored SUVs, driving aggressively to keep a 100-ft. (about 30 m) bubble of space around the client at all times, intended to ward off suicide car bombers. To maintain that bubble, convoy drivers bump other cars off the road, and gunners fire shots into radiators. Iraqi drivers have learned from painful experience to stay well clear of convoys, but in crowded Baghdad streets it's not always possible to swerve out of the way. All too often, accidents turn fatal. (There are no reliable statistics on the number of Iraqis killed or hurt in such incidents.)

Contractors defend their actions by pointing out that they are targeted by insurgent and terrorist groups; convoys frequently come under fire or are hit by roadside bombs and suicide bombers. Aggressive driving is a defensive measure, they say, designed to safeguard their clients. And it works. Blackwater founder Erik Prince told a congressional hearing this month that although 27 of his employees have died in Iraq, no one under the firm's care had been killed. President Bush on Wednesday praised Blackwater, saying, "They protect people's lives. And I appreciate the sacrifice and the service that the Blackwater employees have made."