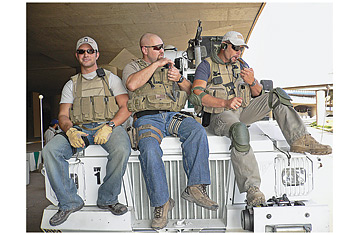

Blackwater contractors sitting on the Mambas at the terminal at Baghdad International Airport after a run, smoking a cigar and waiting for new team members to arrive.

(2 of 2)

But some security men carry the aggression too far, treating all the Iraqis they encounter as potential enemies, using hostile body language and verbal abuse--and sometimes worse. Many uniformed American soldiers regard the contractors with disdain, describing them as reckless and trigger-happy. Since Iraqis don't always distinguish between private and military convoys, soldiers say, bad behavior by contractors only deepens Iraqi antagonism toward the military. "The contractors caused problems that the Iraqi leaders--imams, tribal sheiks, elected officials, military commanders--expected the U.S. [military] to solve," says retired Army Major General John Batiste, who commanded the 1st Infantry Division in Iraq in 2004 and '05. "Their attitude was, They're Americans and therefore they work for you." Last December, a few weeks before the Christmas Eve shooting, a senior Western diplomat told Time he was especially alarmed by the attitude of the men guarding senior U.S. embassy officials. "They behave like Iraq is the Wild West and Iraqis are like 'Injuns,' to be treated any way they like," he said, asking to remain anonymous because of the sensitivity of inter-embassy relations. "They're better-armed and -armored than the military, but they don't have to follow military rules, and that makes them dangerous." The men he was describing worked for Blackwater.

Who Guards the Guards?

Ten months after the Christmas eve shooting, there has been little movement on the case. Moonen's lawyer tells Time his client has not been charged with any crime. Blackwater won't confirm or deny that Moonen ever worked for the firm but has said that an employee was fired for handling a weapon while using alcohol--and that it is cooperating with the fbi investigation into the shooting. The fbi collected forensic evidence at the crime scene, but none of it has been tested in court. Neither the U.S. government nor the Iraqi government can say what laws apply in this case or who has jurisdiction. Vice President Abdul Mahdi's office is angry and frustrated that the U.S. has done little to catch Khalif's killer. "We had hoped the trial would be here in Baghdad, " says Azaid Saeed, the Vice President's head of security, "but, of course, it won't happen; it's only our dreams."

Erik Prince confirmed to the House committee that Blackwater had paid the guard's family $20,000 in compensation. Reached by phone in Baghdad, Khalif's widow Wijdan Muhsin Said would not comment on the payment but told Time she was disappointed that the Iraqi government had not put her husband's killer before a judge. She said she expected nothing to come from the U.S. investigation: "Unfortunately, it seems that Iraqi blood is cheap to them."

In the days after the shooting, relations between Abdul Mahdi's staff and the U.S. embassy grew testy. Some embassy staffers were nervous about driving past the Vice President's guards every day. "We were getting death stares," says an American official. Saeed had to keep his men from storming the gate of the chancellery, where Khalif's killer had taken shelter. He calmed them by saying, "We already lost one. We don't need to lose another 10 and gain nothing."

Inside the embassy, debate about Blackwater's conduct heated up. Stories of Blackwater guards throwing full water bottles at pedestrians and indiscriminately firing warning shots made some diplomats feel as if their security details were undermining their efforts to win Iraqi hearts and minds. Some felt that the embassy's diplomatic-security team, which is meant to supervise all security contractors who protect embassy personnel, was too close to its charges to police its conduct. "They're all drinking buddies, and they cover for each other," says a U.S. embassy official who recently served in Baghdad

But no serious attempt was made to rein in Blackwater until the Sept. 17 shootings. When the Iraqi government temporarily rescinded the firm's gun permits, it forced the embassy to cancel all convoys into the Red Zone. As a compromise, the embassy announced that all future Blackwater convoys will include video cameras and a diplomatic-security agent to keep a close watch on the contractors. Some U.S. Congressmen have proposed legislation to close the legal loopholes that exempt contractors from Iraqi and American laws.

As the larger issues are parsed in Washington, there's a growing sense in Baghdad that private security companies have to change their ways. On Oct. 9, with Blackwater still dominating the headlines, two women were shot and killed by contractors from Unity Resources Group, a Dubai-based Australian firm. It was the same old story: the women's car had come too close to a convoy protected by Unity. It was the sort of incident that only a few months ago might have gone unnoticed. Now Unity is being investigated by the Iraqi government. The days of the cowboy contractor may be numbered.