Sixteen hours had passed since the Twin Towers crumbled and fell, and people kept telling Rudy Giuliani to get some rest. The indomitable mayor of New York City had spent the day and night holding his town together. He arrived at the World Trade Center just after the second plane hit, watched human beings drop from the sky and — when the south tower imploded — nearly got trapped inside his makeshift command center near the site. Then he led a battered platoon of city officials, reporters and civilians north through the blizzard of ash and smoke, and a detective jimmied open the door to a firehouse so the mayor could revive his government there. Giuliani took to the airwaves to calm and reassure his people, made a few hundred rapid-fire decisions about the security and rescue operations, toured hospitals to comfort the families of the missing and made four more visits to the apocalyptic attack scene.

Now, around 2:30 a.m., Giuliani walked into the Upper East Side apartment of Howard Koeppel and his longtime partner, Mark Hsiao. Koeppel, a friend and supporter of Giuliani's, had been lending the mayor a bedroom suite since June, when Giuliani separated from his second wife, Donna Hanover, and moved out of Gracie Mansion. His suit still covered with ash, Giuliani hugged Koeppel, dropped into a chair and turned on the television — actually watching the full, ghastly spectacle for the first time. He left the TV on through the night in case the terrorists struck again, and he parked his muddy boots next to the bed in case he needed to head out fast. But he was not going to be doing any sleeping. Lying in bed, with the skyscrapers exploding over and over again on his TV screen, he pulled out a book — Churchill, the new biography by Roy Jenkins — turned straight to the chapters on World War II and drank in the Prime Minister's words: I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.

There is a bright magic at work when one great leader reaches into the past and finds another waiting to guide him. From midmorning on Sept. 11, when Giuliani and fellow New Yorkers were fleeing for their lives, the mayor had been thinking of Churchill. "I was so proud of the people I saw on the street," he says now. "No chaos, but they were frightened and confused, and it seemed to me that they needed to hear from my heart where I thought we were going. I was trying to think, Where can I go for some comparison to this, some lessons about how to handle it? So I started thinking about Churchill, started thinking that we're going to have to rebuild the spirit of the city, and what better example than Churchill and the people of London during the Blitz in 1940, who had to keep up their spirit during this sustained bombing? It was a comforting thought."

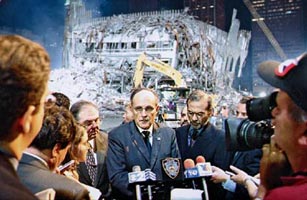

With the President out of sight for most of that day, Giuliani became the voice of America. Every time he spoke, millions of people felt a little better. His words were full of grief and iron, inspiring New York to inspire the nation. "Tomorrow New York is going to be here," he said. "And we're going to rebuild, and we're going to be stronger than we were before...I want the people of New York to be an example to the rest of the country, and the rest of the world, that terrorism can't stop us."

Sept. 11 was the day that Giuliani was supposed to begin the inevitable slide toward irrelevancy. It was primary-election day in the city, when people would go to the polls to begin choosing his successor. After two terms, his place in history seemed secure: great mayor, not-so-great guy. The first Republican to run the town in a generation, he had restored New York's spirit, cutting crime by two-thirds, moving 691,000 people off the welfare rolls, boosting property values and incomes in neighborhoods rich and poor, redeveloping great swaths of the city. But great swaths of the city were sick of him. People were tired of his Vesuvian temper and constant battles — against his political enemies, against some of his own appointees, against the media and city-funded museums, against black leaders and street vendors and jaywalkers and finally even against his own wife. His marriage to television personality Donna Hanover was a war: ugly headlines, dueling press conferences. Giuliani's girlfriend, a pharmaceutical-sales manager named Judith Nathan, had helped him get through a battle against prostate cancer, and his struggle touched off a wave of concern and appreciation for him. But most New Yorkers seemed ready for Rudy and Judi to leave the stage together and melt into the crowd.