Ancient Wisdom

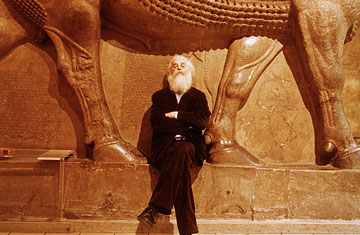

Finkel at home at his sanctuary, London's venerable British Museum

Irving Finkel's unruly beard is a living relic from another era, a gleefully eccentric declaration that he cares little for the conventions of modernity. Indeed, few people live in the past with such delight as the 57-year-old Englishman, who has worked for the past three decades in London's British Museum, where he is the assistant keeper in the Department of the Middle East. At university, Finkel learned to read cuneiform, the oldest known type of writing, in which wedge-shaped symbols were pressed into clay with a reed. His Ph.D. thesis was on ancient Mesopotamian exorcistic magic — the art of getting rid of demons. If you want to know how men were cured of impotence in Babylon thousands of years ago, Finkel can tell you the spell.

But no subject, however esoteric, has consumed him more than the history of board games. At 11, Finkel became so captivated by a book about it that he wrote to the author and went to stay with him. "He showed me his huge game collection," says Finkel, "and it transformed my life." Finkel was especially fascinated by what he learned of the Royal Game of Ur, which was popular in Mesopotamia 4,600 years ago. As a boy, he made a wooden replica of the game, but the rules had long been forgotten. Today, he is the world's foremost expert on the game, and has solved the mystery of how it was played.

Age-Old Obsession In our era of endless distractions, it's easy to forget how important board games were to our ancestors. "There were no entertainments for such a huge period of human existence," says Finkel. "In that environment, games had a fantastically strong hold. They reigned supreme." For centuries, even millenniums, the Royal Game of Ur served as the PlayStation of its day.

Ur was a great Sumerian city in what is now southern Iraq. In the 1920s, an Englishman named Sir Leonard Woolley excavated its royal tombs and dug out five playing boards. The British Museum displays the finest of them — a board that dates from 2,600 B.C. and that is beautifully crafted in shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli, a prized stone imported at great cost from Afghanistan. This "was a state-of-the-art piece of luxury," says Finkel, and it was buried with a princess to entertain her in the afterworld.

Finkel insists that he knew from the age of 7 that he wanted to work at the British Museum. In 1979, he was hired there as an expert on cuneiform inscriptions, "fulfilling in one moment my life's ambition." One of the joys of the job was that he gained access to the museum's undisplayed stash of obscure treasures, including 130,000 cuneiform tablets mostly acquired in the 19th century. Finkel says he has looked at each of them twice. In the early 1980s, he found one with a unique pattern on the back that resembled the squares of a game board.

Written in 177 B.C., the tablet was the work of a Babylonian scribe copying from an earlier document. As Finkel translated the bewildering blend of Babylonian and Sumerian words, he began to realize it was a treatise on the Royal Game of Ur. The author speculated on the astronomical significance of the 12 squares at the center of the 20-square board and explained how certain squares portended good fortune: one square would bring "fine beer"; another would make a player "powerful like a lion."

To Finkel's delight, the tablet also revealed a slew of long-lost details about how the game was played — for example, how the two opposing players used dice made from sheep and ox knucklebones, and what numbers they had to roll before their pieces could be launched onto the board and begin racing around it. According to the tablet, each player had five pieces (though in Ur, they each had seven) and the winner was the person who moved all of them off the board first.

Armed with this new insight, Finkel persuaded the museum to create and sell a replica of the game. Not long afterward, chess legend Garry Kasparov, along with his wife and bodyguard, visited the museum for a private tour, and Finkel gave him a copy of the game. Kasparov's agent later phoned to say the Russian master had spent an entire weekend in Moscow playing it with the French chess champion. The Frenchman "had won by something like 36 games to 29," recalls Finkel, "and was the new world champion of the Royal Game of Ur."

Spread by traders, soldiers, missionaries and other pioneers of globalization, Ur caught on as far afield as Iran, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Cyprus and Crete. While religion has often been "transmitted by violence," says Finkel, games transcend borders because we share a craving for entertainment and competition. The Royal Game of Ur jumped classes, too. In the British Museum, there is a 2,700-year-old graffito version scratched onto a limestone gateway to a palace in Khorsabad, once the capital of Assyria. Carved with a sharp object like a dagger, this makeshift board would have been used by soldiers to distract themselves from the tedium of guard duty.

But all games are vulnerable to the forces of creative destruction, and this one was killed primarily by the arrival of backgammon — a more sophisticated race game in which better players routinely win because the balance between luck and skill has improved. And so it was that the Royal Game of Ur died out nearly 2,000 years ago.

Or so Finkel thought until, to his astonishment, he stumbled upon a remarkable photograph. Tucked away in an obscure journal published by a museum in Israel, it showed a scratched-up wooden board game that had belonged to a Jewish family in the Indian city of Cochin. Finkel collects Indian games, but he had never seen anything like this in India: the board had 20 squares — just like the Royal Game of Ur. He knew that Cochin had, until recent decades, a vibrant community of Jewish traders who came from Babylon more than 1,000 years ago. Was it possible that the game had stayed alive in this insular community, while elsewhere it had become extinct?

Staying Alive Most of Cochin's Jews had long since emigrated to Israel. Finkel has a sister who lives in Jerusalem, so he dispatched her to a kibbutz in the north where many of the Cochin Jews had settled. Finkel's sister went door to door with a drawing he'd done of the board until she found a retired schoolteacher in her 70s named Ruby Daniel, who remembered playing the game as a child in Cochin. Finkel flew to Israel, interviewed Daniel and played the game with her. She told him it was a popular pastime for women and girls when she was growing up, and that she had played it with her aunts on wooden boards, using cowrie shells for dice. By then, each player had 12 pieces, and the placement of the 20 squares had shifted slightly. But it was clearly the descendant of the game played in their ancestral homeland of Babylon 4,600 years ago.

This pattern of what Finkel calls "spread and evolution and decline and rescue and unstoppability" is at the heart of what fascinates him about board games. Intermittently, governments have tried to curb them: China outlawed mahjong during the Cultural Revolution, and the Taliban threatened chess players with execution. But games defy control, mutating and leaping boundaries with an inexorable life of their own. Pachisi, says Finkel, was played in India for centuries, jumped to Britain by 1875 and was repackaged there as ludo, which was exported back to India around the 1960s: "Nowadays, Indian children play ludo completely oblivious to the fact that it is a monstrous decomposition of their own fantastic board game."

Monopoly has proved equally mutable. Invented by a Quaker woman a century ago, it was intended "as propaganda against the wicked practice of speculation in property," says Finkel, but it turned into a blockbuster that "can rouse the most placid aunts to a state of virulent materialism." Finkel is a huge fan, noting that the idea of renting out a square was the last "momentous" innovation in board games. After a lifetime of studying the greatest games, Monopoly is the one he plays most with his five children. But true to the tradition of eternal flux, the family has made some adjustments. "We have a rule in our house," says Finkel. "We all pick on one person and drive them into a fury, which works very nicely. If they kick over the board and say, 'I'll never play again,' that's perfection."

Learn more about the game of UR, or try playing an online version of the game