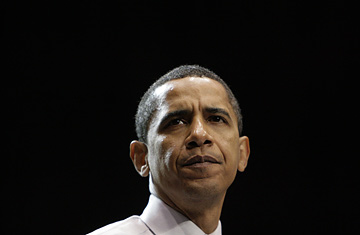

Barack Obama pauses for a moment while speaking at a town hall-style meeting in Winston-Salem, N.C., April 29, 2008.

There was little nuance in Barack Obama's news conference Tuesday, as he pronounced himself saddened, angered and even outraged by the antics of his former pastor at the National Press Club a day earlier. "I find these comments appalling," he said. "It contradicts everything that I'm about and who I am." It was a far different tone from the finely tuned speech on race that he had given in Philadelphia in March, shortly after some of Jeremiah Wright's most inflammatory comments had first come to light. And it reflected the new political reality that Obama has confronted in what have been the rockiest weeks yet for his presidential campaign.

The most important audience Obama was trying to reach in that news conference was not the voters in the upcoming Democratic primary states of Indiana and North Carolina. He was speaking most directly to 300 or so remaining undecided Democratic superdelegates, the party regulars who are likely to determine the eventual nominee — and who have become increasingly concerned in recent days that the Democratic front-runner lacks the fire and the fight he will need to prevail in November. As one Democratic strategist put it: "You could sense, if not a turning of the tide over the past couple of days, that people were getting back on the fence." Indeed, on Tuesday, Hillary Clinton picked up the endorsement of one important superdelegate: North Carolina Governor Mike Easley, who is backing her despite the fact that much of the rest of the state's political establishment has lined up behind Obama, considered a strong bet to win the state's primary next week. "There's been lots of 'Yes we can, yes we should,'" Easley said in a dig at Obama. "Hillary Clinton is ready to deliver."

The setbacks for Obama's seemingly charmed presidential campaign have come one on top of the other lately. There was his admittedly clumsy comments in a private fund raiser about "bitter" small-town voters who "cling" to religion and guns, questions about his association with a 1960s-era terrorist and nitpicking in a recent debate over why he doesn't wear an American flag pin on his lapel.

But potentially worst of all was his association with Wright, particularly after the retired pastor launched what amounted to a media tour and suggested that any efforts that Obama had made to distance himself was posturing. "Politicians say what they say and do what they do based on electability, based on sound bites, based on polls," Wright said dismissively of his former congregant. Even former President Jimmy Carter, who normally avoids commenting on the presidential race, told CNN that Wright had "really been damaging" to Obama's presidential campaign.

Obama's campaign was dismayed as well by the timing of those comments, which came just as their candidate had begun to regain his political footing after being defeated by Clinton in last week's Pennsylvania primary. In particular, they overshadowed campaign events that were aimed at connecting better with senior citizens and blue-collar whites, two groups that Obama has been losing to Clinton. "It's harder to break through if you're spending a lot of time on Reverend Wright," lamented one of Obama's top strategists.

How combative to get in response has been a dilemma for Obama, who has built his entire candidacy on the idea that he represents a new, less corrosive brand of politics. Nor does the roughness of ordinary politics seem to fit Obama's personal style. But increasingly, Democrats have been worried about how well that style will wear if Obama gets the nomination and has to face even tougher attacks at the hands of Republicans. "Sometimes, he sounds like he is writing a Ph.D.," said one adviser. "He has to show some passion."