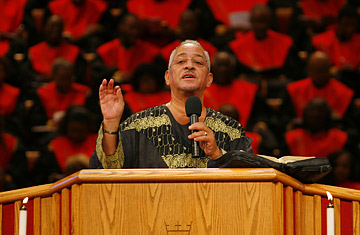

Reverend Jeremiah Wright in 2006.

A few weeks ago, after his former pastor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright Jr. of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, first drew headlines for his fiery sermons, Barack Obama responded with a graceful speech on race in America. But Rev. Wright has decided he isn't about to shut up and launched a series of provocative remarks over the weekend and on Monday. On Tuesday afternoon, Obama denounced Wright, saying "His comments were not only divisive... but I believe that they end up giving comfort to those who prey on hate." The candidate added, "Whatever relationship I had with Reverend Wright has changed as a consequence of this." Whether that is enough to quell the controversy is one thing. But it also continues to raise the question about the preacher at the center of the controversy: What exactly does he believe?

Wright, 66, vented on a lot of subjects at his National Press Club appearance in Washington on Monday. But the venting during his question-and-answer session overshadowed an important point: his attempt to articulate the so-called black liberation theology to which Trinity and scores of other mainstream black churches adhere — and to which he owed his fame and reputation.

Wright's journey to black liberation theology lay through civil rights turmoil and debates about racial identity. He grew up in Philadelphia, the son and grandson of preachers. He enrolled at Virginia Union University, a historically black college in Richmond, during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. In the South, for the first time he saw Christians "who professed faith in Jesus Christ and who believed in segregation, and saw nothing wrong with lynching, saw nothing wrong with Negroes staying in their place," he told Bill Moyers in a PBS interview last week. That experience moved him to leave college for a six-year military tour — first with the Marines, then the Navy. Eventually, he arrived at the University of Chicago's Divinity School.

There he was introduced to black liberation theology, which in the late 1960s was emerging as a more rigorous, if not radical, reevaluation of the role of African Americans in the country's history, with the church as confessional, refuge and bully pulpit. Much of it was a reaction to the Black Power Movement and the Nation of Islam, which questioned the compatibility of blackness with Christianity. "Blacks coming out of the '60s were no longer ashamed of being black people, nor did they have to apologize for being Christian. Because many persons in the African-American community were teasing us, Christians, of being a white man's religion," Wright told Moyers.

In 1972, Wright became head of Trinity, a church on a hardscrabble strip of Chicago's South Side with barely 90 members. The church adopted the slogan "Unashamedly Black and Unapologetically Christian." A light-brown-skinned man with an Afro, Wright regularly wore dashikis, and laced his Sunday sermons with a level of political rhetoric that over the years has often proved too political for some African Americans. Nevertheless, Trinity's congregation grew to some 8,000 (Oprah Winfrey and the rapper Common have attended services there). Wright's prominence in Chicago soon gained him national attention and won him entry into the White House during the Clinton Administration. Trinity became the largest congregation in the United Church, an overwhelmingly white Protestant denomination. Still, says Dwight N. Hopkins, professor at the University of Chicago's Divinity School, and an authority on black liberation theology, "Mainstream Americans have no idea of what the black church is." And, says Hopkins, who is also a Trinity member, "There are just certain people who are looking for an excuse to attack the black church, or black clergy who are prophetic."

Wright retired from his weekly preaching duties in March. Almost simultaneously, the controversy began. Since then his life has been threatened, as has his church. The media barrage was so intense that some reporters apparently called a hospice in an attempt to speak to a dying Trinity member. And so Wright made up his mind to talk. When he got to the NPC, he had a receptive congregation waiting for him. Many of the people "Amen-ing" were attendees at a two-day conference for black theologians and not journalists, who were largely stuck in the balcony. "I know it's hard being quiet when you're attacked," says Vernon G. Smith, chairman of Indiana's legislative black caucus, who says he's known Wright for nearly two decades. Smith, who is concerned about Wright's effect on the May 6 Indiana primary, says he'd hoped Wright would "bear it, and wait," before publicly venting his frustration. But, says Smith, "for anybody who's built a church or institution to try to help the ghettos of the inner cities of America and then have that legacy potentially lost, it's got to be painful."