(2 of 3)

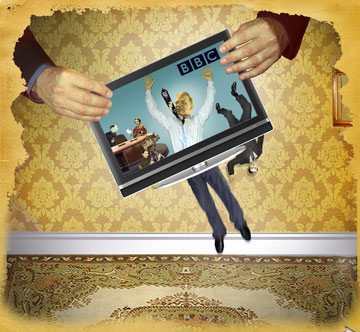

There's one BBC interviewer so confident of skewering evasions that he seems almost languid as he moves in for the kill. Jeremy Paxman's usual quarry are obfuscating politicians, but his target on Oct. 17 was Michael Lyons, chairman of the BBC Trust. Lyons, Paxman's bosses' boss, had agreed to appear on the BBC's in-depth news program Newsnight to give his explanation for staff cuts and other measures the director general would announce the following day. These would include a paring back of the BBC's much-vaunted news-gathering operation. How, Paxman wondered, could such a move be in line with the BBC's public-service mission, defined by its first director general Lord Reith, to "inform, educate and entertain." "Let me give you a list of the distinctive programs the BBC is making," said Paxman, his voice laden with sarcasm. "Help Me Anthea — I'm Infested. Is that the sort of program the BBC should continue making? My Man Boobs and Me. How about that? Help! My Dog's as Fat as Me. Freaky Eaters. Fat Men Can't Hunt." Lyons, flushed under the studio lights, replied that these shows "may well fall very neatly into that category of things that may no longer be made."

These programs have something in common besides the power of their titles to make BBC executives blush: they were all commissioned by the digital TV channel, BBC3. Set up in 2003 to cater to precisely the younger audiences that Byford says are so tricky to retain, BBC3 has scored several successes, including an exuberantly tasteless comedy show called Little Britain. Featuring such popular characters as an incoherent delinquent called Vicky Pollard and a pugnacious, latex-clad homosexual named Dafydd Thomas, who deludedly believes he is "the only gay in the village," Little Britain drew a mass following and won a primetime slot on BBC1. But although BBC3's share of viewers aged 16-24 has risen by 47% since October 2006, its audience still amounts to only a 3.7% share of viewers in that age group. BBC broadcaster John Humphrys, who vies with Paxman for the distinction of being Britain's least emollient interviewer, recently advocated that BBC3 and its posher, arts-oriented sister BBC4 should be axed to save money. After all, he harrumphed, they're watched by "only six men and a dog."

Danny Cohen, BBC3's 33-year-old head, counters: "The danger is that people say the only things that matter about the BBC are the things that matter to me ... We don't make our programs with 50-year-old viewers in mind." Closing BBC3 would be a false economy, he adds: "Channels don't cost money — content does. You could remove BBC3, but you'd still presumably want to provide programs for younger viewers."

His channel is not just about entertainment, insists Cohen, but also meets the other Reithian ideals by informing and educating its young audience on issues such as body image — hence My Man Boobs and Me and the succinctly titled F*** Off, I'm a Hairy Woman. Among new projects in the works are not only TV dramas and comedy programs but also a Web-based experiment, which Cohen describes as a "weird mixture of YouTube and talent show." Part of the BBC's updated remit is to boost the "media literacy" of the British and push the move to digital technology as analog is phased out. BBC3 intends to set trends and not just follow them.

The BBC's enduring belief that it must stay in the forefront of changes in the wider media environment has driven its growth. The Corporation ballooned in the 1990s, adding staff (numbers peaked at more than 27,000 in 2004; they now stand at 23,000 before the new cuts take effect) and diversifying its operations and output. In came the rolling news service BBC News 24 along with a commercial arm, BBC Worldwide. The drive for ratings intensified.

Nobody stopped to ask if the BBC could sustain such growth, or if it was feasible for it to stretch itself in so many directions. Director general Thompson's new plans for the BBC, which he calls Creative Future, reduce staffing and budgets but leave the range of activities pretty much intact. There's a constant tension between the BBC's aim of making what Byford calls "brilliant, outstanding, special, stand-out content that raises the bar of broadcasting" and the Corporation's need to justify its existence by attracting mass audiences, which tend to eschew high culture and serious factual programming. Populism has the upper hand. "If you look at the history of the BBC, it is the history of a very slow retreat from the public-service remit, as if gradually the grass is growing over Lord Reith's grave," says Greenslade.

Reith may well be spinning under the grass, but the BBC isn't alone in its travails. Britain's Serious Fraud Office may review documents obtained from the U.K. communications regulator, Ofcom, in relation to its decision to fine the breakfast TV company GM.TV. In September, the regulator imposed a penalty of some $4 million on GM.TV for encouraging viewers to dial premium-rate phone lines to enter competitions after winners had already been picked. ITV has admitted to similar practices. "Television is at a low point," says Graham Stuart, director of independent production company So Television.

The scandals over rigged competitions reflect the industry's search for new sources of income as its traditional wellsprings — subsidies and advertising revenues — threaten to run dry. There's another reason for falling standards, says Stuart: the huge popularity of reality TV — cheap to produce and capable of provoking the kind of controversy that still hooks big audiences. Controversy is, of course, hard to control. Channel 4's last run of Celebrity Big Brother sparked riots in India after Bollywood actress Shilpa Shetty was subjected to racial abuse from fellow contestants. Earlier this year, The Verdict, a BBC reality show, brought together a jury of celebrities, including the novelist, former politician and jailbird Jeffrey Archer, to rule on a fictionalized rape case. It attracted heavy criticism for trivializing a serious subject, and viewing figures were paltry, too.

If shock tactics don't grab viewers, star power often will. That's the thinking that drives the competition between the BBC and other broadcasters to sign and retain big-name talent. A recent hit for the BBC, a science-fiction-infused detective series called Life on Mars, made for the BBC by the independent production company Kudos Film & Television, won over viewers with its originality and an unstarry cast. It's an exception in an era when schedules at the BBC and at commercial broadcasters buckle under the weight of leaden fare built to showcase stars or to reprise themes that have already proved successful elsewhere. (TV's fictional hospitals now employ almost as many staff as Britain's unwieldy National Health Service).

Graham Stuart avers that broadcasters do need stars. He co-founded So Television with Graham Norton, an Irish-born comedian who fronts BBC chat shows and game shows. Norton "is paid a lot of money by the BBC," says Stuart, but "what we're doing here is show business and everything relies on a small number of talented people who are stars. They're the reason people will switch on." He adds: "If Lord Reith, a cranky old Presbyterian, could use the entertainment word, then other people should be able to, too."