(3 of 3)

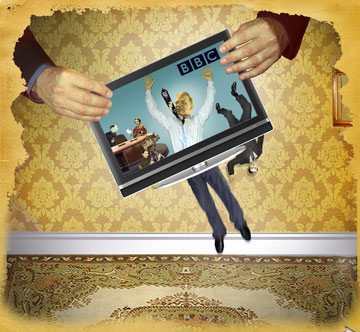

Another cranky presbyterian seems anything but entertained by the BBC. At a September press conference in Downing Street, Gordon Brown gestured to a journalist near the front of the throng, indicating that it was his turn at the microphone. As the journalist identified himself, Brown motioned him to stop. The press conference had barely begun and the Prime Minister had already answered questions from four BBC correspondents. Now here was a fifth. Brown didn't care that each journalist represented different BBC outlets catering to different audiences: to him, the BBC was the BBC and enough was enough.

There's been little love lost between the BBC and the government since the 2003 clash over claims made, in an unscripted on-air exchange between John Humphrys and reporter Andrew Gilligan, that a dossier making the case for the Iraq war had been "sexed up." This led to a judicial inquiry after the source for Gilligan's story, government scientist David Kelly, committed suicide. Strained relations with the government probably did not directly affect license-fee negotiations, but add to the sense that the once-beloved Auntie Beeb has become the relative nobody wants to sit next to at family events. She's unlikely to find a warmer reception from a Conservative government: Tories and Euro-skeptics regularly accuse the BBC of a pro-Europe bias and a left-liberal agenda.

These claims are furiously rejected by the BBC. Byford says it constantly strives for balance and impartiality — for what he calls "a completeness of view." He concedes, though, that the BBC's swarms at news events can seem "incoherent and duplicative." Plans unveiled on Oct. 18 to fuse TV, radio and online newsrooms and lose up to 490 jobs "should have been done earlier," says Byford. "We're a multimedia broadcaster increasingly organizing around a multimedia platform."

Whether or not these cuts deliver the improvements Byford envisages, the spectacle of the BBC targeting such core services and preserving frothier output fuels concerns that it has lost its reason for being. Richard D. North, author of a 2007 book called Scrap the BBC!, calls the broadcaster a "grotesque monopoly" and advocates its privatization. "Broadcasting now needs no more control or support than the print media," he says.

Really? Lift all public-service strictures from British broadcasting and what would remain? North argues that the élite would find a way to ensure that the sorts of programs they enjoy continue to be made. Andy Duncan, chief executive of Channel 4, disagrees, and vehemently. "There would be a huge reduction in the quality of television in this country. If people had a profit motive only there'd be less investment in content, particularly in some of the areas where quite clearly the market wouldn't provide as much."

The veteran broadcaster David Attenborough insists that public-service broadcasting still plays an irreplaceable role in British cultural life. As he sees it, it's pointless to expect individual programs and channels to fulfill all public-service requirements, even though his own natural-history shows for the BBC, including the hugely popular Life on Earth, appear to meet every Reithian ideal. Attenborough shares the view of the BBC's top management that the broadcaster must continue to provide a spectrum of programming to ensure something for everyone. If some people switch off, no matter. "The notion that you shouldn't pay for something if you don't use it is uncivilized," says Attenborough. It's no different, he adds, than having some of his tax money spent on, say, a public swimming pool or library "even though I don't use either."

The new vision for the BBC articulated by its director general Mark Thompson is that it will go on doing what it has been doing, but with fewer people, a greater impact and higher standards. Quality is the key, whether it wears a suit and extracts the truth from politicians or spills out of a comedy character's absurdly tight latex outfit. Delivering quality programming is the only way the Corporation can bear out this claim by its deputy director general Byford: "The BBC is here to make the world a better place." It's down to Thompson, Byford and their beleaguered colleagues to ensure that the world continues to include a BBC that is more than a ghost of what it once was.