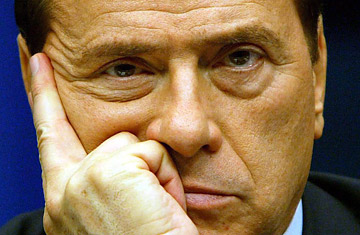

Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi during a news conference in Brussels on Dec. 11, 2003

The four-story palazzo in Rome would become infamous in 2007 when it emerged as one of the prime locations for Silvio Berlusconi's over-the-top parties with young women, hangers-on and at least one professed high-priced prostitute who took photos and secretly recorded conversations with the 70-something Prime Minister.

But four years earlier, I found myself at that same private residence, Palazzo Grazioli, to interview Berlusconi — over lunch. I was working on a story for TIME on how he'd dropped badly in the polls, but my host was rather buoyant after having wrapped up playing host to his self-declared "friend" President George W. Bush, who had been on a three-day visit to Rome. Berlusconi began the hour-long lunch of pasta al pomodoro and Super Tuscan wine by showing me the gift Bush had given to him: sheet music for American standards. Berlusconi even hummed a few bars of "Ol' Man River." That detail would make it into the magazine story. Dessert would not.

We closed our simple but intimate meal with some delicious homemade pistachio ice cream before the waiter served a large porcelain bowl of fresh cherries. The Prime Minister politely offered some to his guest and staffers, one by one. All politely refused. So Berlusconi started on the cherries himself, peeking into the bowl like an emperor to pluck out the choicest of the crop. With the search for each new cherry, he pulled the bowl closer and closer until his left arm was all but wrapped around it. Even back then, the scene struck me as the perfect vision of some not-quite-holy Roman indulgence.

That day is just one memory I find flooding back now that his reign is over. Is it really? For those of us whose stake in Italy extends beyond a week's holiday in Capri or someone's favorite hunk of Parmigiano, we're all still asking if Berlusconi is truly, finally out of our lives.

I married into Italy in January 1998, six months after meeting Monica, a Rome native, when we were both living in Northern California. When we decided to begin our life together in her native city, I knew I'd be doing some fast learning. My famiglia Italiana, in the strict sense, was bound to be a beautiful thing. But there was that would-be member of the extended family settling in down at Palazzo Grazioli. And Berlusconi was destined, for the next decade, to be around every corner, to come up in every conversation, appear on every channel. He was going to enter our lives, get into our heads, shape the future that awaits our children.

For the family of foreign correspondents in Rome, he was also going to provide some great copy. Even before it descended into leadership-by-orgy, the Berlusconi reign featured a steady diet of scandal and surprises and pure star power. There were his fights against corruption charges, his control of the private television network, his foot-in-la-bocca episodes as well as a constant, more subtle eroding of civility and faith in the nation's leaders.

He didn't invent Italy's penchant for explaining away conflicts of interest; he was hardly alone in seeing public service as private enterprise by other means; but it was Berlusconi who dominated an era when bad national habits got worse, a fat national debt got fatter, and the most beautiful parts of Italy were also looking disturbingly backward, while other parts of the world were full steam ahead.

All Italians should pause for a moment now to ask what they did or didn't do to contribute to this poisonous political longevity. His sticking around, his omnipresence, was the worst of all sins. We should all share the blame. Life in Italy can be uniquely beautiful and Italians have a vibrant instinct for creativity and, what may surprise many foreigners, a prodigious work ethic. The problem is that those powers of imagination and 12-hour workdays are often devoted to keeping things stuck in place. That is in part how Italy ended up with him for 18 years. My own mea culpa is easy: I secretly enjoyed covering him a bit too much, for a bit too long. I suspect a lot of journalists did.

But Monica and I moved on to Paris for work. And from there, I had a sinking feeling that Italy isn't a great place these days for our kids to grow up. As a father, I just wanted him to go away as fast as possible.

And so the news of the end came to me, at 9:56 p.m. Europe time, sent from Rome by a member of my extended Italian family, Zio Jacopo. His text message was simple: "It's done. He resigned." This American father of two Roman kids didn't hesitate with a reply: "Viva l'Italia!"

Israely, TIME's Rome bureau chief from 2001 to '08, is co-founder of the global news site Worldcrunch.com and is working on a book about Italy.