In October 2004, shortly after Nigeria's President Olusegun Obasanjo declared that the country had no homosexuals, Bisi Alimi, then 29, decided to come out of the closet on a nationally televised talk show. "Someone had to speak up and put a face to this, and let people know there are gay people in Nigeria," he says. His public disclosure immediately transformed him into a target: the first time he left his house, onlookers greeted him with homophobic slurs, and a group of teenagers surrounded him and started to kick. On April 9, 2007, he faced his most brutal reckoning yet. That night, a group of men burst into his house, blindfolded him and tied him to a chair before repeatedly punching him in the face. "Later I felt something pointed at my head and one of them said, 'Just pull the trigger and let's go,'" he remembers. "I thought that this was going to be the end of my life."

Despite the painful memories, Alimi counts himself among the lucky ones: his neighbor scared off the assailants, and he soon made his way to Britain where he received asylum.

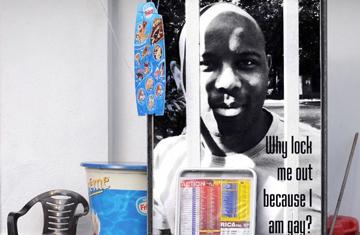

But for the millions of gay men and women living in countries that still criminalize homosexuality, there is no escape from the fear and persecution that remains a part of daily life. More than a third of all countries have laws against consensual homosexual acts. Beyond limiting personal freedom judicially, these laws torment the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community socially by fostering an environment of intolerance. In Malaysia the law allows for a sentence of up to 20 years in prison and flogging, while courts in Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and several other countries can punish offenders with a life sentence. Elsewhere the situation is even graver. Since 2009, Ugandan politicians have pushed for laws allowing death penalty in cases of "aggravated" (meaning repeated instances of) homosexuality. And on Sept. 3, Iran executed three men on charges that they were gay.

With the exception of Iran, each of those countries shares a major historical influence: they were all once part of the British Empire. In fact, it was British colonial administrators who introduced anti-gay legislation to the colonies, where lawmakers kept them on the books after achieving independence. Today 38 of the 54 members of the Commonwealth still consider homosexual behavior criminal.

Now a London-based organization wants to right that wrong. Launched on Sept. 13, Kaleidoscope plans to leverage Britain's political clout to encourage countries, including former British colonies, to revoke their discriminatory legislation. In practical terms, that means lobbying Britain's leading politicians so that ministers discuss LGBT issues as a matter of course whenever they host their foreign counterparts. There's already been a groundswell of support. The organization's launch drew endorsements from the leaders of Britain's three main political parties, including Prime Minister David Cameron. "It's simply appalling how people can be treated — how their rights are trampled on and the prejudices and even the violence they suffer," he said. "I want Britain to be a global beacon for reform."

Multinational corporations have a part to play, too. Lance Price, Kaleidoscope's director, says the organization will also work with big companies he believes share the group's commitment to diversity and LGBT rights. Such firms could prove particularly skilled at influencing governments in developed countries like Singapore, which still outlaws homosexuality. "They have to think about the safety of their own employees and whether the partners of their employees can join them abroad and have a proper life," says Price. "Even if this wasn't morally right — and it is morally right — there are still good commercial, financial and trade reasons for tolerance." Those include boosting the number of gay tourists and attracting more investment.

Changing laws — a Herculean task in its own right — will likely prove easier than changing attitudes. South Africa, for instance, enshrined LGBT rights in its constitution following apartheid, but lesbians there still endure so-called "corrective rapes." Nigerian activist Alimi, who is also a co-founder of Kaleidoscope, says the group will champion and support grassroots activists — the most important elements of affecting change. "There's always been an argument in Africa that homosexuality is a white man's disease," Alimi says. "White gay men cannot lead this fight. It is a battle that has to be led by people on and from the continent who understand the structures there, but with the support of white gay men in the north."

And Kaleidoscope recognizes that. Price says that beyond international lobbying, the organization will provide advice to activists leading emerging and established movements on the ground, and work to increase the dialogue between countries that share historic and cultural ties. The hope is that activists who have made progress in one country (like those in Bermuda, which decriminalized homosexuality in 1994) can illuminate the struggle for their neighbors (like those in Jamaica, which is generally considered one of the most homophobic countries in the world).

It's been more than four years since Alimi, now 35, settled in London. Besides his activism with Kaleidoscope, he also works for an HIV charity in London and has offered advice to a number of Africans who have settled in the city. "So many gay men and lesbians who are refugees in Europe don't believe in Africa anymore," he says, explaining that they "forget" about the continent after securing their working papers. Given their harrowing tales of harassment, it's easy to understand why. But Alimi still dreams of returning home. "I am Nigerian. That's where my life is. That's where my soul is," he says. "I have so much faith in that continent, and I believe there will be change. I want to be part of it." If Kaleidoscope fulfills its promise, he will be.