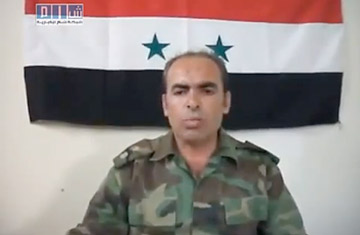

Hussein Harmoush defects in a frame grab taken from a Youtube video.

It was an inglorious turn in one of the more hopeful episodes for the Syrian opposition. In June, a high-ranking soldier, a colonel no less, defected, and quickly formed the "Free Officers' Movement," seeking to rally other military men against the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. In his only face-to-face interview with the media, Col. Hussein Harmoush told TIME this past June that he quit the army, among other reasons, after receiving orders to shoot on protesting civilians.

But on Sept. 15, a disheveled Harmoush, dressed in a white shirt, appeared on primetime Syrian state TV, "confessing" that there was never a band of defectors and that he'd been paid to lie about it by every regime bogeyman (some 300 of them) — from the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood, to the widely despised and exiled former Vice President Abdel-Halim Khaddam and his sons, to Bashar's estranged uncle Rifaat Assad (perpetrator of the infamous 1982 Hama massacre, now living in London) as well as "most members of the Antalya meeting," one of the largest groupings of anti-Assad activists named after the Turkish city they met in months ago.

In a relatively slick set-up, an off-camera male interviewer asked Harmoush a series of questions. The colonel denied that he had ever received orders to shoot at civilians. The first group to contact him was the Muslim Brotherhood, he said. "They said 'what do you want?' I said 'tell me what you have, so I know who I want to work with.' I was getting lots of offers." Everyone "promised weapons and money but didn't deliver," Harmoush said, describing the opposition as "useless."

It's unclear how Harmoush, a native of the pummeled yet fiercely resistant Syrian city of Homs, ended up in regime custody. For the past few months he had been living in a Turkish refugee camp not far from the Syrian border, but according to several people who were in daily contact with the colonel, he slipped out of the camp several times to sneak across the mountainous terrain back into Syria.

He had been missing for more than a week when he showed up on Syrian TV — a state mouthpiece that has broadcast similar confessions activists claim were extracted through torture and threats. Some activists say Turkey handed Harmoush over to the Syrian secret police, a claim Turkish officials have privately denied. Others say Harmoush was nabbed in Syrian territory, ensnared by a regime agent posing as an arms dealer in a sting. Regardless, the majority of Syrian activists seem to lay the blame squarely on Turkey, which they say owed Harmoush a duty of care to protect him. Turkey has kept its southern border with northwest Syria open to the thousands of Syrians fleeing violence, and has housed them in several camps closed off to the media.

When TIME met Harmoush in Syria shortly after he announced his defection he was emotional, tearing up several times as he recounted how and why he deserted. He was torn about fleeing the homeland he had served for 22 years in the military, worried about the parents and siblings he was leaving behind (his family had fled to Turkey), and frightened of being assassinated by regime sympathizers among the thousands of refugees squatting in orchards near the border. One of his brothers was subsequently killed in a raid on Sept. 9, which may or may not have been tied to his capture.

There have been many defections of low-level soldiers from Syria's largely Sunni army, but few high-ranking officers like Harmoush, although it's unknown how many defectors there are. Much of the military's upper echelon is comprised of Assad's Alawite co-religionists, although Harmoush is Sunni.

Colonel Riad al-As'ad, the leader of the so-called Free Syrian Army affiliated with the Free Officers' Movement, warned the Syrian regime in a video posted on YouTube not to harm Harmoush and to immediately hand him back to Turkey, "otherwise we will respond harshly ... through military operations." He also cleared the Turkish government of any wrongdoing, saying officials were trying to ascertain how Harmoush was detained. The capture of such a high-profile defector is likely to deflate the morale of his men as well as the courage of others hoping to break away from the military, something activists are banking on to weaken Assad's grip on power.

The civilian opposition — a hodgepodge of aging intellectuals, leftists, Islamists, Kurds and representatives of the protesters on the street, further split by ethnic, tribal, geographical and sectarian differences, have so far been unable to present a united front to the international community. On Sept. 15 the so-called Syrian National Council was announced in Istanbul, Turkey, with the hope of doing just that. The organization is comprised of 140 members, 40% of whom are exiles, the rest activists within Syria who were went mostly unnamed for their own safety. The council will elect a leader at a later time.

Still, it's unclear if this organization will succeed where others have failed. Just 30 minutes before the scheduled press conference in Istanbul to announce the members, there were still disagreements about how many representatives various Syrian groups should be allotted. There are very real questions about what else, apart from bringing down Assad, the council members can agree on.

The Syrian uprising, which has now surpassed the six-month mark, with more than 2,600 deaths and many more thousands missing, has reached a stalemate. "The truth is, it was all an act," Harmoush said of his reportedly valiant efforts in June to help residents trapped in the besieged city of Jisr al-Shughour reach the safety of the Turkish border. "We said that there were soldiers protecting the people but it was all a lie, an advertisement." More likely, that is precisely what the notoriously pro-regime, inaccurate Syrian TV broadcast this evening.