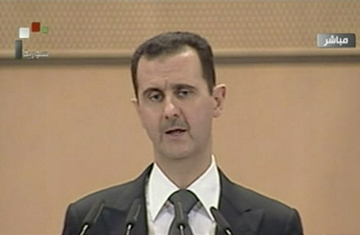

Syria's President, Bashar al-Assad, speaks in Damascus in this still image taken from video on June 20, 2011

Syrian President Bashar Assad used his third televised appearance in the three months since antiregime protests first erupted to deliver a monotonous, rambling and technocratic speech to a handpicked audience at Damascus University on Monday, June 20 — and while the autocratic leader promised a national dialogue, the offer is unlikely to dampen the violent dissent rocking his country.

There was little new in his more than hourlong address. In many ways, it was basically a repeat of his first speech before parliament, on March 30, although the applause was more restrained this time and the 45-year-old leader wasn't interrupted by pledges of fealty. In the first speech, Assad blamed the then two-week-long unrest on a foreign conspiracy to undermine Syria for its anti-Israeli stance. He recycled that claim on Monday, adding that saboteurs — or "germs," as he described them — were, while the most dangerous element to the unrest, also the smallest. The protesters fell into three groups, the President said: those who were peaceful and had legitimate demands the government should meet; "outlaws" and "criminals" whose sole aim was to harm the state (he said there were 64,000 of these — "a small army"); and finally, the extremists and blasphemers who "kill in the name of religion, sow destruction in the name of reform and spread chaos in the name of freedom."

Apart from the renewed promises of an imminent national dialogue and all the talk about setting up committees to investigate reforming various laws, there was a clear, key message: Assad is trying to listen to his people.

The key problem, however, is that he's unlikely to hear a truly representative spectrum of opinion, even though he said he'd discussed "more than 1,200 topics" with scores of delegations from across the country's ethnic, sectarian and geographical divides. Assad must know this, given his mention that only 36,000 stateless Kurds have made use of one of his earlier recent concessions and applied for full citizenship, because "fear has prevented citizens from approaching the state."

He spoke of amending the constitution or even tossing it out and drafting another, of wanting the army to return to its barracks and a resumption of "normal life." But Syria is unlikely to ever be the same again. Assad specifically appealed to the 10,000 or so refugees from the northern town of Jisr al-Shoughour to return from the official Turkish camps and makeshift shelters along a sliver of Syrian territory hugging the Turkish border they have fled to. "The army is there to protect the people," Assad said. But many of those refugees told TIME recently that they will not return to their homes unless Assad's nepotistic regime falls. It wasn't enough that the President's first cousin, the billionaire businessman Rami Makhlouf, announced several days ago that he would be stepping back from business to focus on charity work. "We want Bashar and everyone associated with him to go. What did they teach or offer us except corruption, oppression and death?" says Sharif, a 25-year-old refugee from Jisr al-Shoughour camping out near the Turkish border.

Assad has talked the reform talk since he first inherited power, upon the death of his father Hafez in 2000, but 11 years later, he has little to show for it. He shot back on Monday at critics who question his sincerity — and capability — in bringing real change to Syria, and he indicated that he knows that the stakes, especially regarding the economy, are high. "The most dangerous thing we face in the next stage is the weakness or collapse of the Syrian economy, and a large part of the problem is psychological," he said. "We cannot allow depression and fear to defeat us. We have to defeat the problem by returning to normal life."

Syrian-rights activists were quick to dismiss Assad's speech. Demonstrations reportedly broke out in more than a dozen cities after his talk. "Today it is more clear than ever — Assad cannot stay in power and will not reform," tweeted Malath Aumran, a prolific cyberdissident.

It didn't have to be this way. Assad was given plenty of space and time by an international community keen to see him put his oft referred-to "reformist leanings" into practice and fearful of what may replace his secular, anti-Islamist regime. In many ways, he also had the benefit of hindsight, or at least clear examples of what not to do. He could have learned the lessons of the ousted Egyptian and Tunisian leaders Hosni Mubarak and Zine el Abidine Ben Ali and realized that reforms must be enacted and not merely promised, and that sooner is always better than later. The ongoing armed rebellion against Libya's Muammar Gaddafi provides a clear warning that brute force can help fuel, rather than quell, popular anger. Instead, Assad seems to be a student of the old school, intent on applying the "Hama rules" of his father, whose barbaric suppression of an uprising in the city of Hama in the 1980s served as a potent deterrent to would-be dissenters for decades. More than 1,400 people have been killed in three months, rights activists say, in weekly protests that have become as predictable as they are bloody.

Although Assad opened his speech on Monday by acknowledging the "martyrs on both sides" and that "innocent blood was spilled," he said there could be no reform in the middle of "sabotage and chaos." But it's unclear how much time he will have. In his address, he referred to the possibility that the unrest may continue for months or even years. Syria's antigovernment movement, however, may have a shorter time frame.