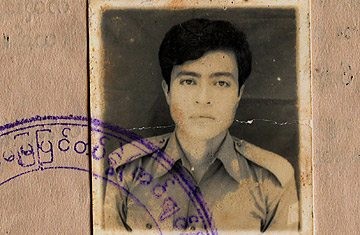

A military photo of Myo Myint, as shown in the documentary film Burma Soldier

Burma has been rendered in journalism, activism and art as a country of plain dichotomies: good vs. evil, liberty vs. suppression, the saintly Aung San Suu Kyi vs. the brutal monolith of the military junta. By its very premise, Burma Soldier, which airs this evening on HBO, muddies this picture. The documentary's subject, Myo Myint, is a former soldier who gave his adolescent years to the regime but came in adulthood to join the democratic opposition against it. Says Nic Dunlop, writer-photographer and a co-director of the film with Annie Sundberg and Ricki Stern: "Myo Myint's story is extraordinary because it incorporates victim and perpetrator in a single narrative." Extraordinary, yes, and yet this project's greatest strength is its willingness to consider that the lowest ranks of the Burmese army are rife with men as petrified and cynical of the regime as the people they terrorize in its name.

Much of Burma Soldier consists of an unsettling monologue, filmed almost entirely at a refugee camp of grassy huts on the Thai-Burma border. From there, Myo Myint waits to be granted asylum, like his siblings were a decade ago, in the U.S. He came to the army, he tells us, as most Burmese soldiers: teenaged, apolitical and looking for employment and esteem. "Then I didn't know the difference between people showing respect and people acting out of fear," he says. He revisits the details of atrocities committed by fellow service members and to which he was a reluctant witness — the raping of ethnic-minority women, the torching of their villages — in quiet and deliberate tones. The interviews were shot in the less than two weeks before Myo Myint boarded a plane for America, but his narrative has nothing of this urgency.

Myo Myint worked as a military engineer, laying and clearing minefields, until an enemy mortar shell set off a mine and blew away a leg, an arm and a few of his fingers. Recalling his subsequent time in hospital, he sheds tears so suddenly that he seems to startle himself. As a crippled civilian, he would retreat first into drink and later, with a yen for peace, into the pro-democracy movement. He established a youth library of banned books, met with democracy leader Suu Kyi and, as protests rocked the country in 1988, addressed a rally of 8,000 antiregime demonstrators from his crutches. More than 200 men in uniform, emboldened by his example, joined the uprising. For defying the dictatorship, Myo Myint was tortured and sentenced to first seven years, then almost immediately after his release, 10 years in prison. He served close to 15.

Burma's generals came to control what had been a newly independent nation in a bloody coup in 1962, one year before Myo Myint was born. In the decades since, the junta has waged an endless civil war against ethnic groups, formed an economic oligarchy, defied international pressure and gunned down pro-democracy demonstrations. "The lower ranks, most of them are illiterate and uneducated," Myo Myint tells TIME, "and they're brainwashed into thinking that all dissidents are enemies of the army, of the state, of the people." In 1990, the regime nullified an election that would have brought Suu Kyi's now banned National League for Democracy party to power. For 15 of the past 21 years they kept her locked up. Last November, Suu Kyi was released from her most recent term of house arrest and in March, a new military-backed government was sworn in, but seemingly little has changed.

Burma Soldier punctuates Myo Myint's grim chronicle with scenes of this junta rule, footage of troops battling protesters or parading in shows of malevolent force. Much of it was smuggled out of the country by dissidents, the rest taken from the BBC, a Burmese humanitarian-service movement, the Web and even a spate of foreigners on gap year. "Begged, borrowed, stolen and in some cases actually paid for," says Dunlop of the images. But for all its impact — there is something uniquely horrifying in watching an army fire on its own people — the material is rarely as effective as Myo Myint's defeated but still handsome face.

Months before that face was set to speak to a foreign audience in its HBO debut, the team behind the movie focused its attentions on Myo Myint's countrymen. In an act of what producer Julie LeBrocquy has christened "reverse piracy," Burmese-language copies of the movie are being smuggled back into Burma. Activists are taking great risks to leave DVDs behind in Rangoon's Internet cafés to be discovered by future cyberusers. By a recent count, the Burmese-language version had been viewed online close to 33,000 times.

In Fort Wayne, Ind., where he now lives among the largest community of Burmese Americans (and where the film's end captures his fateful reunion with his family), Myo Myint is working still to give Burmese an account of their own history that hasn't been written by the ruling elite. And that includes his current neighbors. For while he has gladly found the plentiful and uncensored stacks of an American library, many of the Burmese in Fort Wayne cannot read English. He acts, among other things, as a translator and interpreter for incoming refugees and has his hands in both a local Burmese-language magazine and weekly Burmese-language TV program. "I have no right to directly participate in Burma's politics," says Myo Myint, who took with him to the U.S. a plastic bag of Burmese soil. "So this is my politics: struggling to help my people, my nation." It is a striking patriotism for a man who is not allowed to go home.