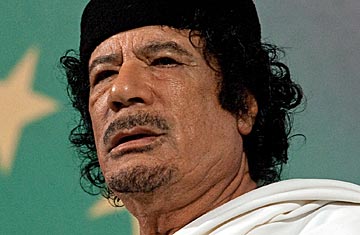

Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

The violent clashes between Libya's security forces and protesters this week, which has killed almost 100 people and injured dozens more since last Tuesday, looks a lot like the rumblings of another Arab revolt. To some observers, the oil-rich country's longtime leader Moammar Gaddafi suddenly looks as vulnerable as Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and Egypt's Hosni Mubarak were during the uprisings that eventually ousted them.

But unseating the region's longest-serving ruler after 41 years in power will require a much bigger show of strength than protesters have so far been able to muster. In the process, they might have few allies to count on: Not the country's military, much of which is loyal to Gaddafi, nor necessarily even Western leaders, who have much to lose in a major upheaval in Libya.

Hundreds of pro-Gaddafi demonstrators have marched in the capital Tripoli in recent days, holding posters of The Brotherly Leader, as he's known at home. And as long as the anti-government protests remain largely confined to cities about 600 miles east of Tripoli, Gaddafi still appears to be comfortably in control, governing from his desert tent on the outskirts of the city. "This is significant in that these are the biggest protests we've seen," Heba Morayef, Human Rights Watch researcher for the region, told TIME from Cairo on Saturday; the organization has estimated this week's death toll at 99. "But until there are big demonstrations in Tripoli they do not pose a real threat to Gaddafi."

This week's protests are unlike any seen since Gaddafi seized power in 1969 in a bloodless coup as a 27-year-old military officer; the last serious protests, in 2006, were briefer and smaller. Overnight Friday, thousands of people, including lawyers and judges, camped outside the courthouse in Libya's second-biggest city, Benghazi, where the protests began last Tuesday, only to be attacked by special forces early Saturday morning, according to the AP. Since Wednesday demonstrations have spread to four other eastern cities as well. Pro-government militia fought fierce battles against demonstrators in Benghazi and another eastern city, al-Baida, on Friday, according to witnesses cited by AP. Other clashes occurred when mourners burned police stations in al-Baida after burying 15 protesters shot dead on Thursday by security forces. And on Saturday, according to the AP, snipers opened fire on mourners at a funeral for protesters, leaving at least 15 more dead and many wounded.

A tight clampdown on media coverage makes it difficult to gauge whether the clashes are the start of a bigger revolt or just a fleeting show of dissent. In stark contrast, for example, to Bahrain, where scores of foreign journalists are covering the protests, news organizations are almost entirely shut out of Libya, relying on shaky cellphone videos or text messages uploaded to Twitter and Facebook accounts to decipher what is happening; on Saturday, the government reportedly shut down Internet access across the country. Scores of Libyans have called into the news desk of Al Jazeera, which has aired numerous accounts since Tuesday, even though they are unable to verify the information. On Friday night Mohammed El-Berqawy, an engineer in Benghazi, reported on Al Jazeera that "tens of people are dying in Benghazi today." "The wall of fear has come down," he shouted in the telephone on air, in a tearful account of the mayhem in the Mediterranean port city. "Where is the United Nations? Did Gaddafi bribe them with his millions?"

El-Berqawy's question hits at a crucial hurdle for anyone seeking to end Gaddafi's rule: Libya's immense wealth. With 30 billion barrels of oil reserves in the country — nearly $3 trillion worth at current world prices — Gaddafi is sitting on a mountain of cash. Libya's vast foreign reserves, estimated at about $160 billion, have barely dipped during the global recession. About 100 oil companies, including Chevron and ExxonMobil, have poured into the country since U.S. sanctions against Libya ended in 2006. Just as the first protests were kicking off last week, the Russian energy giant Gazprom signed a major gas deal in Libya.

And so far, the huge influx of new wealth into Libya has not created a new middle class demanding rights that threatens Gaddafi's rule. Yet it has caused deep divisions within Libya's top officials — and even within Gaddafi's own family. That could offer anti-government protesters their best shot at unseating Gaddafi, and ending his bizarre governing style of ruling through Revolutionary Committees.

Gaddafi's second son Saif al-Islam is the West's clear favorite to succeed his father, and has strongly pushed a liberal, open economy and greater personal freedoms — evoking the wrath of his brother Motassam, who is Libya's national security adviser, and occasionally angering his father too. When I visited Saif at home in Tripoli last year, he told me that Libyans wanted Western-style human rights. "If you are against that, you are an idiot." Saif's emerging power has resulted in his political allies pushing for greater political openness; those include Libya's crucial oil chief, Shokri Ghonem, a close ally of Saif. But in an interview in Tripoli last year, Ghonem said many officials would fight against giving citizens greater political rights. "There are a lot of people for whom reform is not in their personal interest," he told me. "It will not be a walk in the park." With the bloodshed already this week, Ghonem's remark looks like a prescient warning.